THE LOOP

8 March 2017

Loop into hallucinatory video, an online realm dedicated to the Carel Fabritius painting The Goldfinch and articles about a James Baldwin documentary, the 19th century origins of “empathy” and how refugees stay in the loop via mobile phones—and you can help.

A Documentary Envisions a Book James Baldwin Never Finished

Lauren finds a sensitive response in Hyperallergic to a new documentary by Raoul Peck on James Baldwin titled I Am Not Your Negro. It resonates creepily with the Australian context.

“In the film, [Baldwin] refers to white America as ‘monstrous’ at least three times. He explains why: because people in the US are caught between narratives as to who they actually are and who they want to be, and narcotizing, populist television circulates a story that always emphasizes the latter…The film left me with questions that I suspect won’t be answered in my lifetime, because successive generations of Americans have been brought up with the conviction that they need never understand anyone, not even themselves. How do I live with that?” ¬

Discover the story of The Goldfinch

The Goldfinch, a bird’s eye view

Lauren discovers a new online exhibition by Mauritshuis Museum in the Hague that reveals the techniques, influence and hidden history of one of its most popular paintings, Carel Fabritius’s The Goldfinch (1654), as well as its connections to literature, including Donna Tartt’s Pulitzer-winning 2013 book with the same title. A fully-integrated experience combining painting, design, words and sound, it’s a fascinating example of how the internet is becoming art’s new natural habitat, even for the most traditional forms.

“A little painted bird. Carel Fabritius saw it: the beauty of the black, yellow and red in front of the white wall. The light and shade. A single glistening beady eye. The shadow on the wall. He painted the bird—a goldfinch—with loose, visible brushstrokes. Not too much colour or detail. A little bird on a chain, in front of a rather battered wall. That is all. Not much, but just enough.”

Dream Study (Hibernation) by Kamil Franko

A new moving image work, Dream Study (Hibernation), published online by BOMB magazine, occupies a strange, lovely space somewhere between video and cinema. Shot in Zagreb, Croatia, it evokes the early surrealist works of Luis Buñuel.

“Hibernation became a way to derail linear time. Watching the seasonal shifts in Sljeme—the orange turning black, my repetitive routine of filming, the movements within the frame—all somehow speak a language of circular progression. Hibernation, as in a dead-like sleep, spirals into a never-ending journey.”

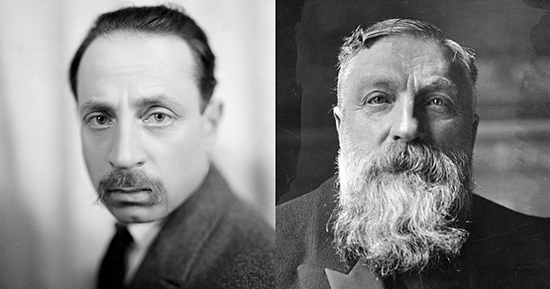

Rainer Maria Rilke, Auguste Rodin

The Invention of Empathy: Rilke, Rodin and the Art of “Inseeing.”

Long fascinated by the workings of the perceptual phenomenological loop that is our experience of art, Keith chanced across a book review and felt an urgent book purchase coming on. Writing about Rachel Corbett’s You Must Change Your Life: The Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin on her invaluable Brainpickings blog, Maria Popova focuses on the book’s initial account of the emergence in the 19th century of “einfühlung” (“feeling into”). The notion was principally conceived and developed by German philosopher Theodor Lipps—a key influence on Freud, Kandinsky, Rilke and Merleau Ponty—and translated as “empathy” by British psychologist Edward Titchener in 1909. With “empathy” nowadays deployed so casually (often desperately as we invoke it in the face of the effects of disaster, war and Neoliberal cruelties) it’s reinvigorating to read of its origins in an understanding of the art experience: “Lipps originated the then-radical hypothesis that the power of [art’s] impact didn’t reside in the work of art itself but was, rather, synthesised by the viewer in the act of viewing.”

Migrants with mobiles: Phones are now indispensable for refugees.

If you need a charge to power up your empathy for refugees around the world then consider your relationship with your phone. The prostheses that are mobile phones are so integrated with our minds and bodies we feel disabled when they break down are lost, stolen or run out of power or credit at the very times they are most needed. But we can usually handle it. However, for millions of refugees, power and credit are life sources and their phones sometimes more important than food, as reported in The Economist that grabbed Keith’s attention.

“Migrants with mobiles” is an eye-opener, revealing the astonishing scale of mobile phone activity by refugees: keeping in touch with family, calling for rescue, protecting unaccompanied children, researching government routes and work prospects and getting an online education (not least in coding). In camps, people gather with their phones around power sources, a few aided with credit by the likes of Phone Credit for Refugees and Displaced People and Mercy Corps in Lesbos and Athens. You can help buy time and credit by making a donation.

–

RealTime issue #137 Feb-March 2017