An Australian sect saga

Luke Goodsell: Rosie Jones, The Family

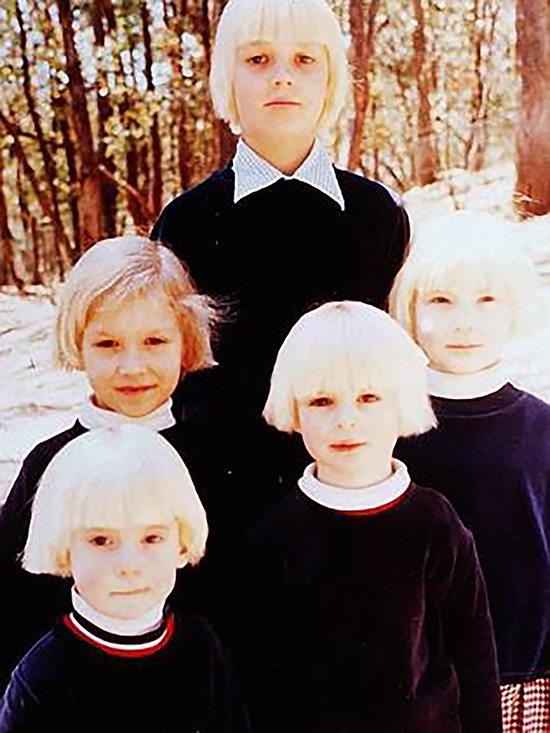

The Family, Eildon children lined up according to height, The Family

Pop’s fascination with cults shows little sign of waning, from recent American documentaries like The Source Family (2012) and Jonestown (2013) to deep-dive true crime podcasts, the Manson family’s enduring appeal, superstars with messiah complexes, like Kanye West, and the chic imagery appropriated for fiction films like The Sound of My Voice (2011) and Martha Marcy May Marlene (2011). With its provenance in Melbourne International Film Festival’s production funding program, Rosie Jones’ new documentary explores one of Australia’s most infamous New Age sects, The Family. Led by magnetic mother figure Anne Hamilton-Byrne, this would-be utopia made headlines for allegedly stealing and mistreating children from the late 1960s through the early 1990s.

A yoga teacher turned charismatic enchantress, sect co-founder Byrne believed herself to be a maternal messiah, and set about acquiring her own family of identikit foster kids for her retreat at Lake Eildon, in rural Victoria. “Aunty Anne,” as the kids knew her, readied her cosmic minions for the new awakening via a mismatch of religious philosophies and the promise of intergalactic ascendancy, which Jones and her animators convey with evocatively loopy psychotropic graphics. Her allure, her followers argued, marked her as a powerful woman and thus a prime target for Australia’s dual enforcers of middle class morality: the police and the mass media.

The Family commences with the 1987 police raid on the sect’s compound and plays out like a thriller, complete with a climactic Hollywood stakeout, that feeds into the collective lust for justice that’s become the staple gambit of hit Netflix series. It’s a savvy move: the entertaining slickness of Jones’ approach—an aesthetic collage of high-end true-crime recreation, creepy home movie footage and emotional survivor interviews—bends this weird and woolly narrative into what passes for an audience-satisfying resolution, keenly designed to prompt indignation and wring tears.

Five of the boys raised at Lake Eildon, The Family

Intercut with the police hunt for Byrne is the soul of Jones’ picture—interviews with the shell-shocked survivors who speak with an often haunted affect, which the director accentuates with subtly edited talking-head clips staged against eerie mall photo backdrops. The Family doesn’t miss a stock footage opportunity to cast Byrne and her sect-keepers as malevolent horror movie ringleaders, from disturbing LSD dabbling to Children of the Damned (1964) inserts to an hallucinogenic montage cut wonderfully in the freakout, brainwash style of The Parallax View (1974).

There’s no doubt the childrens’ story is the tragedy of the piece, yet the film at times risks trite othering of those outside the established norms, often ceding its voice to men of ‘reason’ like lead investigative detective Lex de Man—an archetypal Aussie copper whose relentless pursuit of Byrne and subsequent emotional response betray a weird undercurrent of patriarchal triumph. In doing so The Family dances around a larger tale of mental illness and a failure of women’s health care—in which thousands of often teenage mothers were shamed into giving up unplanned babies for adoption—that not only furnished the sect with fresh blood, but arguably positioned Byrne as a preferable option to unpredictable, often abusive, foster care.

Jones’ doco infers that Byrne was pure evil, but uncovers little evidence that her motives went beyond delusional good intent at best, and psychologically damaging exploitation at worst. Granted, administering LSD to kids isn’t the ideal way to realise one’s visions of utopia, but what’s left uninterrogated in The Family is Byrne herself, whose own troubled history might have added a crucial dimension to the story. When the film finally does get to Byrne, an hour in and with sympathies firmly and unshakably entrenched, it’s astonishing: the impoverished, orphaned daughter of a Melbourne railway yard worker and an institutionalised, paranoid schizophrenic mother, her life could make for its own documentary—and in another film, perhaps an American one, Byrne’s ascent from state ward to doyenne of her own mini empire might have been a tale of overcoming adversity (albeit of the cautionary rise and fall variety.) Yet by dumping Byrne’s story into less than a minute of montage, Jones carefully eschews such complexity, where a more formally adventurous work might have wandered at a remove.

But grey zone morality isn’t The Family’s mandate. The film is always at its most poignant when it focuses on the stories of the survivors, whether conveyed in grainy police interview footage or clips of the weary, but inspiring, adults they’ve struggled to become today. Still, one wonders at the possibilities if Rosie Jones had been permitted access to Byrne, still alive at 96, suffering dementia and reportedly nursing a plastic doll in an aged care home, perhaps somewhere, deep down, communing with a pan-dimensional being from the future.

Leeanne, one of the children raised at Lake Eildon and Anne Hamilton Byrne

The Family

Leeanne, one of the children raised at Lake Eildon and Anne Hamilton Byrne

The Family, director, writer, co-producer, Rosie Jones, cinematographer Jaems Grant, editor Jane Usher, art director Georgina Campbell, producer Anna Grieve, 2016

RealTime issue #138 April-May 2017