Video art treasure house on demand

Conor Bateman: access, quality & streaming portals

Problematizing Pleasure/Punk Theory, VDB TV

We all know that the web has forever transformed the way that films reach us by shifting eyes from the cinema to video-on-demand. But how is the distribution of video art changing in a digital age? Thanks to the internet, we’re able to access a mammoth quantity of film works within a few clicks. The sheer volume is deceptive; we persist with the illusion of a well-nourished collective media diet. But services like Netflix, which currently dominates the Australian streaming landscape, consistently push viewers to the familiar, whether through focus-group tested original television programming or selective acquisition of blockbuster films.

There’s limited commercial appeal in moving image works that push the boundaries of their form; despite several major streaming platforms in Australia, none actively pursue a representation of experimental cinema or video art. Of any major player globally, Fandor, an American streaming service, comes closest to this pursuit, with licensing agreements with artistic organisations like Canyon Cinema and The Film-Makers’ Cooperative.

Access = poor images?

The emergence of online streaming creates, at face value, yet another conflict between authenticity and access in the distribution of artists’ moving image works. Erika Balsom, in her comprehensive new book After Uniqueness: A History of Film and Video Art in Circulation (Columbia University Press, 2017), writes that the continuing presence of “traditional values of authenticity and rarity” looms large over video art distribution. Like previous shifts in distribution, the contemporary move towards online streaming involves an implicit quality loss. The reduction print championed by Stan Brakhage in the 1960s was similar in nature, a distribution model that allowed viewers to purchase 8mm film prints of experimental film works for affordable repeated home viewing yet at inferior quality compared with the 16mm originals. But digital streaming goes further in radically altering the context of viewing.

Artist and writer Hito Steyerl refers to moving image works distributed online (legal or otherwise) as “poor images“; wide circulation is clearly prioritised over image quality and fidelity. The best example of a loosely curated streaming service heavily reliant on Steyerl’s poor images is UbuWeb, an online archive of avant-garde art founded by conceptual poet Kenneth Goldsmith in 1996. UbuWeb offers low-quality copies of video art among its vast (and legally dubious) collection. Goldsmith has written in defence of his site that it exists as a “provocation” aimed at distributors, challenging them “to go ahead and do it right, do it better, to render Ubu obsolete.”

The continued existence of UbuWeb suggests that we have not yet reached that “right” point. Though in the last decade streaming services which offer up experimental works have emerged, they differ from UbuWeb (and, in turn, the notion of the reduction print) in that that they provide no option for consumers to purchase work. These sites instead draw on a rental model that came to define video art distribution throughout the second half of the 20th century.

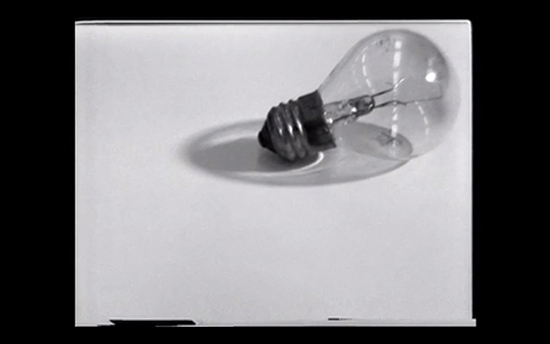

John Baldessari, Inventory

From the co-op to the streaming portal

Emerging from artist-run co-ops in the 1960s, the rental model saw video art move away from a limited run approach to distribution, wherein works of moving image media were treated like any other artwork, bought and sold and kept in private collections. In the 1970s, the establishment of the Video Data Bank in Chicago and Electronic Arts Intermix in New York City set a template for organisations involved in renting and distributing video art. Both are still operating today as online databases, primarily for the benefit of educational and archival institutions, which can order copies of the works starting at USD$100 each.

VDB, though, has embraced the promise of online streaming. Launched in May 2015, VDB TV consists of short, curated video programs comprising works from the VDB archive, presented every two months and available to view for free. The strengths of this approach lie in the curatorial element; the VDB TV programs are essentially educational in nature, exposing viewers to a range of video artists and their work, as well as providing expert commentary. Recent programming at VDB TV has centred around a decade-by-decade look at American video art in honour of VDB’s 40th anniversary in 2016. A recent highlight in this series was John Baldessari’s amusing Inventory (1972), in which he presents around 30 objects ascending in size, accompanied by his detailed and deadpan voiceover narration. VDB TV also focuses on the contemporary.

One of the first VDB TV programs—FEELINGS, curated by writers Leo Goldsmith and Rachael Rakes—featured more contemporary fare, including Jesse McLean’s Somewhere Only We Know (2005), which challenged the emotional manipulation embedded in American reality television by re-purposing its images. We’re watching contestants from various reality TV programs on the verge of tears when an earthquake interrupts a Big Brother episode and a news anchor suggests that their lived experience is merely entertainment.

Like VDB, LUX, a London-based arts agency, offers both an online database of its film collection—from which institutions can order copies—and a streaming service. Its video-on-demand service LUXPLAYER launched a few months prior to VDB TV. LUXPLAYER offers films for a 48-hour digital rental, at US$4 a pop, regardless of the runtime. Some of the films can be streamed for free within a limited window as well.

What makes LUXPLAYER particularly compelling in the online video art landscape is that much of its video content is available in high-definition format, a feature not matched by VDB. Unfortunately, the player isn’t very often updated with new content; most of what is available to rent right now has been there for over 10 months. That said, the service remains the easiest way to view a film like William Raban’s experimental documentary Thames Film (1986), a landscape essay film charting the changing perceptions of the titular river, which outside of LUXPLAYER is only available on DVD in the United Kingdom. It’s also the only non-educational service where you can watch Chain (2004), Jem Cohen’s fiction feature debut scored by Canadian post-rock band Godspeed You! Black Emperor.

Video art in the curated online gallery

More regular catalogues of video art available to stream online come in the form of virtual art galleries, curated online spaces which screen works for a small window of time and which are free to view. Balsom uses Vdrome, an arm of Italian publisher Mousse, as her central example of this approach, noting that the site draws on “the dialectic of rarity and reproducibility.” Launched in February 2013, Vdrome streams one artist’s film at a time, for a 10-day period, in reasonably high quality format and, like VDB TV, with an accompanying curator’s text or interview with the artist. The collection has since found a physical home at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD), where one of the site’s curators, Jens Hoffman, has served as Senior Curator since 2012.

The films screened on Vdrome tend to come from already notable video artists and experimental filmmakers, like Jonas Mekas and Ben Russell. Its curation can’t be aesthetically or conceptually pigeon-holed; in the last year, Vdrome has screened films like the surreal Wutharr: Saltwater Dreams (2016), from Australian artists Karrabing Film Collective, and an extended music video, Sticky Drama (2015), from Jon Rafman and Daniel Lopatin (aka Oneohtrix Point Never).

The limited windows approach that Vdrome uses has been replicated on a variety of other websites which screen, though are not limited to, video art and experimental film. Le CiNéMa Club, a French “online cinema,” screens short film works for free, one at a time. It tends to screen often overlooked work from established filmmakers, though it also includes notable short works from the international festival circuit. In 2016 it screened What Happened to Her (2016), Kristy Guevara-Flanagan’s collage film about the depiction and prevalence of murdered women in popular American crime films and television programs.

Kinet, a Canadian publishing platform run by independent filmmakers Kurt Walker and Isaac Goes, operates in another direction, presenting four works of experimental or avant-garde film every few months, notably drawing from filmmakers working outside existing filmmaking or academic structures. Zachary KerrHolden’s The MovieLand Movie (2016) is a recent highlight, an experimental documentary about a rivalry formed in a Vancouver arcade. In the same vein (though not a free service), tao films operates as a curated VOD platform focused on what has become known as “slow cinema,” allowing for works that were often very difficult to see outside of specialty film festivals to reach a new audience online.

Atlantis, Ben Russell

Multiple platforming

It’s worth noting that many of the films screened on these video platforms are not necessarily restricted to one service or method of distribution. Often films that screen on Vdrome eventually end up on another online platform, whether a rental and educational distribution service like VDB or placed online by the artists themselves on Vimeo. Ben Russell’s Atlantis (2013), which screened on Vdrome 6–19 May in 2015, is currently available to watch through VDB (educational licenses), Fandor (streaming subscription) and Vimeo (free to access, uploaded by the artist).

Breaking the analogue mould

In a discussion published by Rhizome in 2014, artist Jason Simon positions the question of online streaming of artists’ moving image works as one of cultural and economic restriction:

“The entire economy of gate-keeping distributors is rooted in analog, that is, pre-digital culture. Breaking that mold without destroying their economy is the puzzle, and perhaps the solution lies somewhere in subscription streaming portals.”

These streaming sites, from the expansive UbuWeb to tightly controlled Vdrome, don’t yet offer up a total solution to the ultimate question of authenticity versus access. That said, the recent proliferation of sites like VDB TV and Vdrome, strongly tethered to discussion and criticism, suggests an encouraging (and ever-widening) path for viewers to watch and learn about works of moving image art.

Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg, Delights of an Undirected Mind, 2016, VDROME

RealTime issue #138 April-May 2017