Revelation Film Festival: the joy of bafflement

“We live in a world where there are big films like Alien: Covenant that shine a light into and explain the darkness,” Revelation Perth International Film Festival Program Director Jack Sargeant told RealTime in the lead-up to the festival’s program launch last week. “I grew up with horror films where you didn’t explain the darkness. I find the cultural desire to explain everything really depressing.”

Since its inception in 1997 by founder Richard Sowada, Revelation has maintained a commitment to delineating a space for watching and discussing daring works of independent cinema in counterpoint to the mainstream cinema market. Now, with the festival approaching its 2017 instalment, 6-19 July, both the social and cinema worlds have grown ever-more conservative and difficult to comprehend.

For Sargeant, cinema offers something less than instructive and more interpretive — a place of strange images, sounds and narratives even more fantastical than the real world oddities of President Donald Trump’s tweets, alternative facts and unwinnable wars. “Explaining a truth is overrated in film,” says Sargeant. “I quite like films where nothing is explained. There’s a pleasure in not having a reading of everything.”

Richard Sowada and Jack Sargeant

This approach has produced an eclectic collection of films for the 2017 festival that are “from all kinds of worlds,” and which don’t direct the viewer on how to think. The program encircles what Sargeant calls “weird indie films,” art-house dramas, music and art documentaries, queer films, horror films and children’s films. As well as the continuation of the festival’s academic conference sidebar, there’s “an event called Revel8 that is all about Super 8 film and Super 8 filmmakers; so we have a real love of the living culture of film as a physical medium.”

“All these different kinds of cinema matter,” says Sargeant, despite the fact that most of the films aren’t securing general releases beyond the festival circuit. Notwithstanding their divergences in genre and subject matter, the films Sowada and Sargeant have programmed share the quality of both expressing and contextualising today’s strange feeling of global confusion, and of being part of the “whole world of filmmakers not getting noticed,” despite the popularity and abundance of film festivals.

Women Who Kill

The collision of the horror genre with queer themes is another often-unnoticed realm. Though a highlight of Sydney’s Mardi Gras Film Festival earlier this year, Women Who Kill (2016), will not be securing a general cinema release. Sargeant describes this brilliantly architectured genre film, by debut filmmaker and web-series comedian Ingrid Jungermann, as revelling in “lesbian camp and deadpan” humour. Jungermann’s Morgan is a true-crime podcaster whose rampant commitment-phobia leads her to believe that her new girlfriend, Simone, is not just an eccentric, fallible human but a sociopathic murderer. The film’s central conceit of fear of relationships is transformed into literal horror, the conventions of crime-mystery and slasher films deftly adopted to insert the viewer into Morgan’s paranoid inner world as it grows impossible to know if her fears are real or imagined.

Another curatorial focus is a stream of films in the quasi-documentary mode between fact and fiction. “We live in an era of fake news and virtual existence. I think these hybrid documentary/fiction films expose that,” says Sargeant.” But they also expose our desire for it. It’s that psychological thing of wanting our own confusion to be contextualised. Everything is sort of baffling and strange, and I really want to see films about bafflement. Confusion is a good thing.”

Houston We Have a Problem

The internationally co-produced docufiction, Houston We Have a Problem (Žiga Virc, 2016), runs in this vein. “It’s about the relationship between the USA and Yugoslavia in the space race in the 1960s,” says Sargeant. “It has philosopher Slavoj Žižek in it saying ‘Even if it didn’t happen, it’s true!’ It’s hilarious, with all the touchstones of hybrid documentary cinema today.”

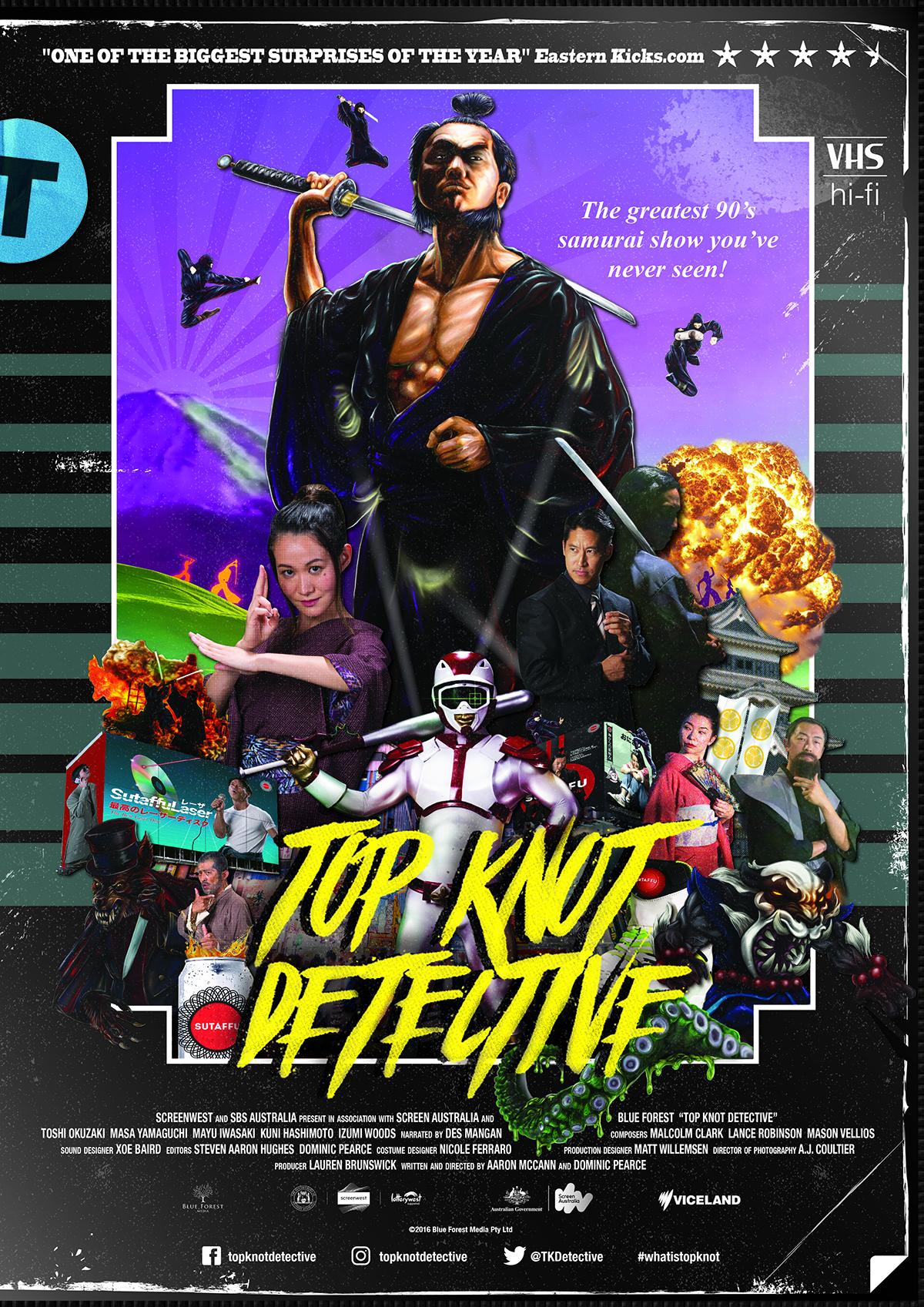

Top Knot Detective

Top Knot Detective

The Western Australian film Top Knot Detective (Aaron McCann and Dominic Pearce, 2016) deploys the mockumentary format to present an homage to “an imaginary cult TV show, and they interview everyone involved in it. You would not know that the TV show is not a thing. It really plays on the audience’s collective experiences and shared cultural memories about half-remembered late night TV. It’s very funny.”

“There is a real sense that both narrative fiction and documentary film aren’t quite enough anymore…[hybrid documentaries] are about how we create, construct, view and examine myth and history. They are just one of the edges of the program, but there are lots of edges.”

A home for the slow-burn film

In its 20th year, Revelation functions at an ironic edge of the film industry, too. The increasingly franchise-soaked film market has led to a growing conservatism and monopolisation of both mainstream and arthouse cinema programming, which has partly led to the space for film festivals to grow and nurture small films squeezed out of general release in cinemas. As such, Sargeant sees Revelation as a unique space in Perth for slow-burn films at the edge of film culture to get a big-screen life.

Cinema: the group experience

Despite the attractions of video-on-demand and home entertainment, “people want to watch films on the big screen,” says Sargeant. “Contrary to popular belief, they don’t just want to watch them on TV. The big screen spectacle is what cinema is all about, the communal experience. My go-to is always Rocky Horror Picture Show. You can’t dance to that by yourself at home. In the cinema it makes sense. When you watch a horror film, you need to be around 200 people. When you’re watching a romance, you want to be crying with everyone. Cinema’s a group experience, and that’s key to our pleasure of cinema.

“There’s a film festival every day of the week. But they all have their own energy and their own identity. Revelation has its own energy. We’re all film nerds, we’re all fans. We have academics and non-academics who are experts in their area. We’re not snobby. I’m not really interested in good film taste. I’m interested in all the different types of culture — music, art — and that feeds into the programming.”

–

Revelation Perth International Film Festival 2017, festival director Richard Sowada, program director Jack Sargeant, Luna Palace, Leederville, Perth, 6-19 July

Top image credit: Women Who Kill