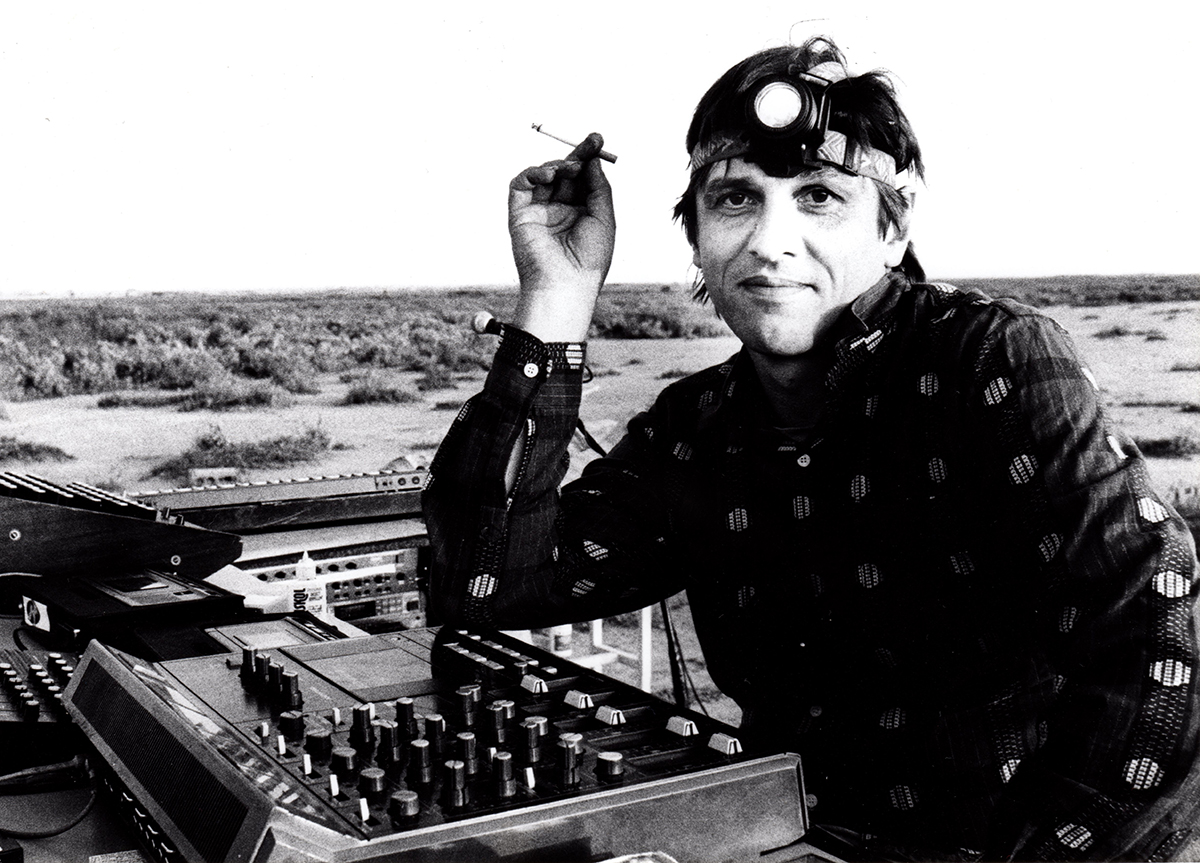

Rik Rue, sound collagist

In 2003, I interviewed Rik Rue for the ABC Australia Ad Lib website. I asked if he thought of himself as a musician or a sound artist. After inhaling deeply on a cigarette, Rik put it like this: “Certain musicians said, ‘Come on — you are a musician,’ but I adopted the word ‘sound artist,’ and now I’m saying ‘sound collagist.’ There’s been all these terminologies — appropriator, plunderphonics — right up to the current one, bastard pop, where people have combined two artists in pop, riffs and bass guitar from one well-known recording, and they’ve made new combinations.”

Personally, I never thought there was anything wrong with being called a musician — someone who brings music into existence. And since a useful definition of music is well nigh impossible (see the book Rosenberg 3.1 — not violin music for 130 definitions of music in the 21st century), it’s hard to get a grasp on what exactly sound art is. “Privileging sound” or “sound as primary medium” does not really help us; all musicians should be concerned with sound. Many sound artists have had training in the visual arts (but so had many of the rock stars from the 1960s), so that’s not particularly useful either. Someone who had no academic training in the visual arts or music but who I would call a sound artist is Rik Rue. If anybody conjures up the notion of a sound artist, I’d say he does.

Rik has been living with MS for many years now and is no longer active in recording and performing. I thought it would be timely to write about him, because bound up with his life and output is a remarkable history of sonic exploration and performance in Sydney that thrived well below the radar of official music and art practice in the 1970s and 1980s. Despite or because of the internet, I’ve noticed that many practitioners in areas of the sonic arts have no idea what went on then. This unknown history, and some of it (before the gentrification of inner Sydney) was extremely wild and raw — manifested in activities generally beyond the world of academia (notable exceptions being the music department at La Trobe and Martin Wesley-Smith’s electronic music studio at the NSW Conservatorium).

One possible definition of a sound artist might be “someone in touch with, and gifted with the touch to reveal, the sonic culture of their time.”

In the beginning

Richard Banachowicz (he changed his name to Rik Rue) was born in Balmain in 1950, the son of a metal worker. His mother was a seamstress. Rik’s parents had emigrated to Australia in 1948, escaping the ruins of World War II. As a kid, he remembers the joys of tuning the dial of the family’s short wave radio as about the only hands-on musical experience that came his way. Except for the choir, his high school offered little in the way of musical sustenance.

As an adult, with the arrival of quality mobile cassette recording technology, Rik found a medium with which he could listen, learn and create with inquiring ears. Like a DIY 19th century explorer and anthropologist, he discovered and collected many of the sonic elements of Sydney (much of which was considered detritus) and revelled in the results. Armed first with Sony, then with Tascam machines, vari-speed, the use and misuse of a pause button, the intrepid sound artist went to work — unpaid work, that is.

Rik earned his living in those years at Newton’s herbal pharmacy mixing potions of who knows what. Jim Denley, founder of The Machine for Making Sense, also remembers that pharmacy: “I would often go there to exchange cassettes and talk music in the aromatic back room. The conversation would get animated as we discussed recent performances, cassette releases, or general gossip. I often wondered how accurate the measurements of the potions were during these sessions.”

An other Sydney

Prior to his taking up with a Tascam four-track Portastudio, I witnessed Rik perform on a number of occasions — usually on a shrieking saxophone, once punctuated with feet stomping on yelping toy frogs at St Johns’ Church, Paddington, and another time on amplified cauliflower at the (Walter Burley Griffin-designed) Paris Theatre on the corner of Hyde Park, now a tower of apartments for the wealthy. This stunning building was pulled down in 1981, one of many crimes committed by the real estate hoods who run this town. The Paris Theatre was frequented, and in part financed by, Patrick White and housed the experimental theatre of Jim Sharman, among a host of other activities, including improvised music and a gay activist film festival. Rik managed the concerts of ‘other’ music at The Paris. I already saw Rik, however, primarily as a performing recordist — a notion long before it was fashionable to perform field recordings and take sound walks (and before someone gets upset, these are all excellent ecological activities).

Clive James titled his much-loved book Unreliable Memoirs for sound reasons: recollection of places, names and occasions can become jumbled over time. As far as I recall, after my migration to Sydney in 1976, Rik was the second person I met who was enchanted with experimental music (the first was composer David Ahern, by then an alcoholic, who I came across by chance in the pub at the end of our street in Balmain shouting ferociously about Stockhausen at a few nonplussed people propping up the bar).

Apart from the Paris Theatre, Rik was involved with organisation and performance at a number of locations — unlike today, they were all free to use. An incomplete list would have included the ICA (Central Street opposite Hoyts entertainment on George Street), Betty Kelly’s Sculpture Centre, Old Marist Brothers School, Art Industry Empire, Frank Watters Gallery, Darlington School (it was free then), Cell Block Theatre, the old Performance Space (Cleveland Street), Stephen Mori Gallery, ICE run by Ian Hartley (founder of Yellow House, Ice, Spurt magazine documenting Sydney’s punk and new wave scenes), Exiles Book Shop (included a rooftop concert with the audience set up in chairs on the dividing strip and the opposite side of the street. Not all neighbours were so enamoured with improvised music and I remember a loud firecracker being thrown through the window at one concert. Rik recorded events such as these and many more).

Amanda Stewart has commented on this wealth of cultural cache back then: “There was a sense of integration of the arts into the city and there were also heated debates about the ethical and aesthetic merits of the various activities. I saw Rik as being very much at the heart of such activities, as well as being engaged internationally, networking within music, sound art, cassette culture, collage, postal art, radio and other systems of sound and art production and distribution. After I first met him, I remember being invited round to his place in Pyrmont where we’d talk until the wee hours about sound, writing, music, film, visual art, politics, radio, you name it. He’d always have something new to play or show you. He was an autodidact par excellence and a virtuosic networker who, with seemingly boundless magnanimity and energy, linked so many people and their art and musics across the globe.”

In Sydney, there were also jazz clubs where improvised music would be tolerated like the (old) Basement, Pinball Wiz, Jennie’s Wine Bar, The Paradise Club (Kings Cross); commercially viable rock venues like The Trade Union Club in which new and experimental music could be heard. At the same period of time SPK, Severed Heads, Dead Travel Fast, and bands of beautiful incompetence like the Slug Fuckers were to be heard — but that would be another story. Jaimie Leonarder’s Mu Mesons brought the music of artists with disabilities into public awareness and celebration. A secondhand shop like Ashwoods was stocked with obscure albums including those on the Obscure label.

Apart from the klang and twang of urban Sydney, Rik documented the spaces where the suburbs stumbled into the stubborn bush. At the time I lived on Dangar Island on the Hawkesbury, and I remember Rik taking the ‘tinny’ (small metal boat) out to witness how the sound of the river water resonated on the face of the sandstone outcrops.

Beyond Sydney and into cassettes

Jim Denley recalls how Rik nudged him into the big outdoors: “I often accompanied Rik on field recording trips around the outskirts of Sydney — he needed a driver. He encouraged me to bring my flute. At Darkes Forest west of Madden’s Plains on the plateau above Wollongong we were recording one day, and he suggested that I duet with the frogs. I felt uncomfortable playing outdoors and said to him, ‘What am I gonna play?’ He said, exasperatedly, ‘Just play!’ I put that track on my first solo cassette release and I noticed that it got the most comments. We didn’t have ‘likes’ in those days. I’ve been playing and recording outdoors ever since.

“On another excursion in the Royal National Park, Rik was recording around a pond, he wanted me and Stevie Wishart to throw tiny pebbles into the water so he could record that delicate sound. Stevie got hold of a large boulder and took it up the rocks overlooking the pond, launched it in, making a huge wave and lots of noise. Rik with headphones on, and gain high, wasn’t amused. I don’t think she ever came on these trips again.

“When he was recording material for his seminal release ‘Ocean Flows’ we drove up the central coast and did recording around beaches in Bouddi National Park. I was always amazed when we arrived at a beach that he didn’t get the recording gear out, he would often light up a fag and sit down. At first I thought this was part laziness, part nicotine addiction — but I came to realise he was observing and listening to the place. He did that first.

“We’d all got used to Rik’s brilliant use of cassettes in performance, so when he turned digital and started using mini disc players, I guess in the early 90s, we were concerned that something would be lost — it was a very different playback machine. Within months he worked the devices out — exploiting their random shuffle, and pushing them way beyond what they were designed to do.”

Rik on radio

Through this period Rik ran a program at 2MBS FM called Stops, Gaps, and Measures on Tuesday and then Thursday nights — it lasted until the mid-1990s. As with many programs allowed into 2 MBS at that time, the output was contemporary, radical and challenging. Many of Rik’s field recordings (obsessively concerned with water and wind) made it straight into the radio ether within days of the field trip. Stops, Gaps, and Measures was one of a number of programs that pushed the boundary of what radio could be. One program rebroadcast live (illegally) the ramblings of a right wing shock jock with suitable contradicting commentary. Another time, the station was briefly taken over by sex workers, although my source cannot recall the reason as to why. Innovative sound tracks to experimental films filled the airwaves in the slots from midnight to dawn.

“I am the radio!”

So there we all were, assembled at The Goethe Institut in Sydney — an odd mixture of recognized composers, radio producers and complete outsiders. I’m not sure what Klaus Schöning (a high-flying producer and advocate of radio art from WDR Cologne) expected in the Antipodes, but Rik Rue was probably not listed on his agenda. After about an hour of polite conversation about radio, art, the meaning of life, and what a wonderful thing it was that we were all there and talking about it so well, Rik (sitting at one end of a very long table) suddenly leaned forward and without warning sent a cassette tape whizzing, rattling and spinning towards Klaus (who was sitting at the opposite end of this huge table). The room went politely silent and although it could only have taken two seconds for the projectile to reach Klaus, it took minutes of diplomatic embarrassment for the professional radio people in the room to recover.

“Thank you,” said Klaus awkwardly surprised and handling the cassette and the situation with some care. “I am the radio!” announced Rik in a loud voice and with his usual uncensored bluntness. Something real and confrontational had entered the proceedings. “That’s it, that’s it! We are all radio,” a relieved Klaus burst out and, for the first time in the meeting, became his congenial self.

Pedestrian, the label

Rik started his own cassette label in 1981 and, for one who walked around recording for much of his time, wryly named it Pedestrian. I was inspired by this cheap and cheerful possibility and stopped trying to produce vinyl albums for my own label (Fringe Benefits) and moved to cassettes myself. US guitarist Eugene Chadbourne visited for the Relative Band Festival of 1984. Seeing the DIY logic, he went back to the States inspired and started cranking out cassettes. A few years later, on tour there, I discovered Rik had become something of a cassette legend as Eugene spread the word on the antipodean recordist. Pedestrian ended up with 15 releases, three involving Shane Fahey in the collaborative Social Interiors. Others involved experimentalists such as Ernie Althof. Despite the fact that all these sonic artefacts are no longer available, if you put “Rik Rue Pedestrian Cassettes” into Google, there are 239,000 results — there must be some collectors out there. Dub for Saint Rita, Voice Capades, Bend an Ear, Other Voices, Ocean Flows, A Raise of an Eyebrow, Sound Escapes, Rue L’Amour — all classics of the medium.

“An alchemy of understanding”

In the early 1980s, it was still possible, via a slip road, to get within 15 metres of runway Number 1 at Sydney Airport; today you would be arrested. Rik and I spent an afternoon there, me whirling an amplified violin around my head, while Rik recorded the planes taking off. Every few minutes, one by one, the jets wiped out the sound of the violin — strangely appealing to a violinist such as myself. Rik documented many street performers, the more oddball buskers, and the regular soapbox speakers at the Domain, the latter forum providing a fecund mixture of religion, politics and philosophy along with active and abusive heckling as part of the show — a grassroots critical theatre.

Rik found objects of social documentation that others might miss. For example, walking home one day in Sydney (circa 1980) he saw a cassette lying in the gutter. Others might not have bothered with such material but Rik picked it up. It turned out to be The Boomerang Cassette Club, an aural chain letter whereby people (mostly old blokes and non-musicians) around the world, interested in recording their daily activities, kept in contact with each other. Rather like a journalist photographer, a sound artist can simply require timing and curiosity to be pertinent. In an interview with Roger Dean for Sounds Australian in 1991-2, Rik saw himself more in terms of stirring and applying heat to the sonic pot, referring to his approach with improvisation as “an alchemy of understanding.”

I’m trying to think of one event where Rik and I were involved that would encapsulate the urban culture of the early 1980s in Sydney. Louis Burdett is/was one of the most naturally talented of musicians anywhere, but often captured by circumstance. On one occasion, he ended up in hospital after somebody hit him in the head with a crowbar. He was hospitalised with mercury poisoning on another occasion after putting his arm through a television set installation as part of his solo performance at ICE. So no surprise that we were also witness to the notorious concert when he was attacked by a group of outraged women while running around his drum kit naked with a functioning firework displayed in, and being emitted from, his posterior. Later in the concert, one enthusiastic male member of the audience grabbed Louis’ penis as a dancer was being asphyxiated from the smoke in an overhead net (having dropped the knife with which to cut himself free from the net and jump into the hopefully surprised audience at a peak point in the performance — the peak came and went and only weak cries of ‘help, help’ from above alerted us to the near-death experience attached to the ceiling). Somehow it isn’t like this is in Sydney anymore!

Rik in the Machine

In the 1990s Rik became a member of The Machine for Making Sense. Jim Denley remembers: “When we were on tour with MFMS it was often quite exhausting, and we’d arrive tired at some train station or airport to be picked up by promoters or organisers — we could always rely upon Rik to be social. He would get in the front seat and start chatting away, eager to understand the local conditions, so the rest of us could curl up and get some rest in the back. He is intensely interested in people. He had instant radar for pretentiousness in collective playing. Whenever he thought things were getting too self absorbed he’d find some sample to explode the moment, and sniggering while playing it — he saved us so many times.” Amanda Stewart concurs:

“A lot of our tours with Machine For Making Sense were intense and Rik’s resilience was astounding. After travelling and performing long hours, day after day, he’d be ready for yet another all-night-get-together of fervent exchange with local artists and organisers in each city. His warmth, humour and candidness drew people to him. If he wasn’t talking sound, he’d be working on it. I remember waking up in the Austrian mountains one morning to find Rik up and about already, keen to play me a new piece. ‘When did you have time to do that?’ I asked him. Apparently, he’d been out recording in the snow during the night and had then composed and completed this new work while the rest of us were asleep. It was nothing to him; just music as usual.

“In MFMS gigs, Rik would frequently leave me gobsmacked. Some of the things he would do in his playing seemed physically impossible and I still don’t know how he did them. As well as being a master of recording and creating new sound and listening environments, he was a brilliant collagist, reconfiguring all manner of materials he found in the world with deft discernment… playful and often transgressive. In some ways, he is also a poet, of sorts.

“Rik’s insights can be utterly surprising at times. He will frequently say what one is thinking almost before one has thought it. If I wasn’t such a skeptic I’d say he is deeply psychic, both musically and in his understanding of the human condition and its motivations. He can smell a rat a mile off and is extremely streetwise and perceptive. You can’t get away with anything!

“We were both quite verbal people, jostling for space in our different ways. At such times we’d look at each other ironically and repeat, ‘Yes. Words, words, and more words.’ Ruark Lewis actually made Rik an artwork embodying this phrase.”

Rik’s other dimensions

In 1993, I invited Rik into the Violin Music in the Age of Shopping project that premiered at The Eugene Goossens Hall, Sydney — a direct broadcast with musicians, sound effects devices, a choir hooked up from Perth, and a live performing audience (try suggesting that now to ABC management!). To my joy and amazement, Rik had created several hundred sonic items from the iconic Exchange and Mart second-hand shopping magazine — all in alphabetical order – an inventory from the ragged edges of late capitalism before the cavalry arrived to rescue it with the trumpet blasting charge of the internet.

Between 1994 and 2007, Rik worked comprehensively with Alan Schacher, both individually and with his innovative performance group Gravity Feed. Alan recounts the special relationship: “In that time we created over 20 projects: all the ensemble works plus my solos, two dance videos, an installation, a rural research project and an industrial residency in Nuremberg. Rik always mixed live, a maestro on five or six devices both MD and CDs on the desk.

“Rik is a profound listener, passionate about natural and found sounds, industrial as well metropolitan environments, spoken word and the deconstruction of language, with a droll sense of humour and a wealth of artistic references. As a performer I felt enveloped and transported by Rik’s dense, visceral atmospheres and architectural constructions. It was sound to inhabit, not music to perform to. Involvement with Rik has offered me a deep insight into and involvement in the sound art world. His legacy is that every sound plays a part, every environment has its unique resonance.

“We had some great times, some funny experiences and some serious disagreements as the ‘odd couple,’ Rik a chain-smoking night denizen and me the early riser. Rik wanted to grasp the sequences of the choreography as a beginning, middle and an end, trying to catch up through the night with the changes that had occurred during the day’s creation. But in my view, Rik worked not to catch up, but to overtake us, leading us into overpowering landscapes we could never have anticipated.”

A savage world of sound

Rik described his work to me in 2003 for Australia Ad Lib: “You get a photograph of a mountain and a few trees and put it up on your wall and it’s pristine, but if you’re in that field, it’s quite physically and emotionally dangerous, the photo is sterilised, I’ve had a leech crawl into a DAT machine and I could never find it, I once lost a microphone up a pig’s nostril, they were very large show pigs, I crawled into the pen and got what I wanted but the pigs pinned me up against a wall, I had to get the steward’s electric prodder out to get these three pigs off me. Another time in Paris — I was blown out by the sound of the turnstiles in the Metro, the ticket mechanism is loud, I bent over, I had my Walkman earphones on, I felt a tap on my back and it was two policemen saying, ‘What the hell are you doing? And don’t come back!’ Once a snake nearly bit me because it came up right behind me — when I’m in those environments even breathing can affect the recording, you make yourself passive and the environment turns on you — it’s quite savage out there.”

Rik is connected by umbilical cord to this savage world of sound and, in particular, to the sonic history of this country — he is an exemplar of what it means to be a sound artist. Tess de Quincey is another performer who has shared the ‘savage out there’ with Rik: “Fantastically, he showed up at (Lake) Mungo armed with a recorder and a sleeping bag. It was such a huge act of generosity to join us researching out there. He chuffed off independently early mornings and came back with a wealth of sounds we all pored over in the evenings around the fire, whilst he intoned and drawled the details of where each sound came from. It was my first learnings about the Australian bush and Rik was a mad guide. It was one of those effortless collaborations — manna from heaven.

“Rik was engrossed with the Long Grass [in Darwin] and those living there on the margins of existence. He managed to weave this spirit into the sounds of the performance. And while we were sweltering in 50º heat and dripping as we mounted the damn plumb-bobs in the roof above the lighting rig, a concerned phone call came through from the presenters in Alice to say that the press in Alice had just run a headline ‘Butch-master comes to Alice.’ The joys of the automatic spell check: butoh had morphed to butch. Rik didn’t let that one go for some time.

“Rik’s one of the pivotal people in my life in Australia. I love his generosity of spirit, his laconic mode, and his ability to pinpoint the obscure and vibrate this into the immense.”

–

Contributors: Jim Denley, Amanda Stewart, Alan Schacher, Tess de Quincey.

You can see Rik Rue with The Machine for Making Sense in Stephen Jones’ video of the group recorded at the Sydney Opera House in 1994 and produced in 2008 here.

In a frank and entertaining 2012 RealTime TV interview, violinist, composer and instrument maker Jon Rose talks with fellow musician and improviser Jim Denley about his early instruments, his relationship to the Australian landscape and what really makes him play.

Top image credit: Rik Rue at Lake Mungo, 1992, photo Heidrun Lohr