In Profile: Sarah-Mace Dennis

Gail Priest

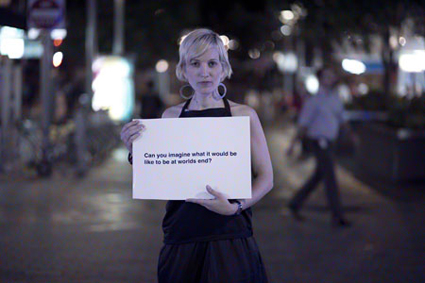

Sarah-Mace Dennis, Do you protest in silence (work in development)

courtesy the artist

Sarah-Mace Dennis, Do you protest in silence (work in development)

Histories, ghosts and memory are consistent themes throughout Sarah-Mace Dennis’ interdisciplinary practice, involving text, photomedia, performance and video. I first came across Dennis’ work in 2004 when she was collaborating with Svenja Kratz on a series of projects inspired by the historic goldmining town Hill End in regional NSW.

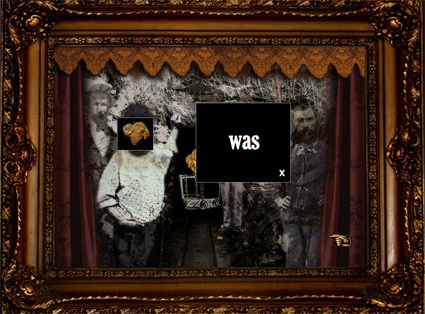

A story of infanticide and suicide, To Rose (my Love) (2004-5), was an interactive video installation in which the viewer’s shadow falling on the screen in the gallery revealed ghosts hidden within the image. The culmination of the series was the hypermedia work Di.O.ram.a: Constructing a Virtual Memory (2007), a journey of image and text uncovering real and imagined stories from the town circa 1872. These early works were impressive for their blending of both real and imagined histories and their technically ambitious formats.

Sarah-Mace Dennis & Svenja Kratz, Di.O.ram.a: Constructing a Virtual Memory (2007)

courtesy the artists

Sarah-Mace Dennis & Svenja Kratz, Di.O.ram.a: Constructing a Virtual Memory (2007)

Shared histories, public memories

Dennis’ most recent work continues these earlier preoccupations but on a much larger scale, thanks to a series of public art commissions. The first of these was Moving over the shoreline, commissioned by art+place (2007-2012), the body responsible for managing the funds raised from compulsory cultural contributions levied on new commercial building development projects in Brisbane. Moving over the shoreline is a two screen, permanent video projection on the façade of the Queensland Multicultural Centre, drawing on historic and contemporary stories about immigration and particularly inspired by Yunguba House, the Brisbane immigration depot in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Dennis interviewed people who had lived at the depot when they first arrived in Australia, as well as more recent immigrants. She also worked with local ethnic dance groups. She says, “I decided I was going to work with ethnic dance groups which might have been a strange decision [for a contemporary art project] but it made complete sense to me because I used to be a Scottish dancer and I know how those traditional dance forms are punctuated by narratives that belong to the traditions. I also wanted to have some Indigenous representation in the work, so I was really lucky to be connected with the dance group Nunukul Yuggera. I only really controlled [the shape of the work] or scripted it from colonisation onwards; so I told the group how my work was evolving across the two screens and then we worked together on how they wanted their story to be told in that.”

Sarah-Mace Dennis Sounds from the Emergent State, commissioned by the State Library of Queensland for the exhibition Live! Queensland Band Culture.

courtesy the artist

Sarah-Mace Dennis Sounds from the Emergent State, commissioned by the State Library of Queensland for the exhibition Live! Queensland Band Culture.

Dennis’ most recent commission is her most ambitious to date. For the State Library of Queensland’s exhibition Live! Queensland Band Culture, Dennis created the six-channel video installation Sounds from the Emergent State. For this exploration of the relationship between music, politics and social and cultural change in Queensland from WWII to the end of the 90s, Dennis used archival footage and interviews with people from the music industry, also getting them to ‘perform’ their responses in the style of Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” She explains, “Queensland is so amazing in terms of music I did feel overwhelmed at first. I thought I can’t possibly tell this story myself, it’s the story of all these amazing musicians who’ve lived in this state. I wanted them to perform in the work because I wanted to acknowledge the people who’ve been working so hard and making those contributions behind the scenes.”

Sarah-Mace Dennis, Mondo Ghilles (2010)

courtesy the artist

Sarah-Mace Dennis, Mondo Ghilles (2010)

Personal histories, embodied rememberings

In terms of the way these stories unfold Dennis believes, “the best way to tell history is by dispersing it across multiple frames, fragmenting it so that viewers are getting traces and they’re putting it back together through their own bodies, by the way they move through things or the way they connect things perceptually.”

Dennis knows first hand what it’s like to piece fragments of history, her own history, back together. In 2008 she was involved in a car accident resulting in a severe brain injury. After time in a coma, she awoke paralysed and with amnesia. Over an intensive period of rehabilitation she regained the use of her faculties and she has made several works that explore this experience of re-embodying and re-discovering her “self.”

For the 2010 Next Wave festival Dennis was commissioned to make a dance film for Nat Curiso’s Private Dances. As part of her rehabilitation, Dennis went back to Scottish dancing (at 15 she’d been competing at championship level). Mondo Ghillies mixes this form with a kind of Vivienne Westwood baroque punk visual aesthetic resulting in a haunting short film. “Mondo Ghillies was about developing my film practice at the time and experimenting with dance film. But in that project I was still very inside the experience. It’s still dealing with the trauma of waking up and being paralysed and not being about to think as you used to.”

Dennis’ Swallow, currently in development, offers a different perspective on the experience. “Since Mondo Ghillies I have done a lot of writing about the event, so Swallow is from a [more reflective] position. The work has multiple characters that I play myself. The idea is that these are really ghosts of myself that I became during my recovery. With a brain injury you go through these really remarkable changes where you think, ‘My brain is functioning again, I’m back to normal.’ But it’s a little bit like the feeling I had when I was a teenager when I thought, ‘Now I’m grown up.’ A year later I looked back and went, ‘Wow, I just didn’t know anything then’…The work really is reflecting on what it means to be a person with no brain, how that challenges your perceptual frameworks and your identity—how you even come to comprehend existence.” Heath Ledger also has a ghostly cameo: Dennis, while in her coma, seemed to absorb the news of the actor’s death, knowing this fact on waking.

Dennis has also written extensively on these experiences as part of her Masters in film theatre and media (UNSW, 2013); she’s currently completing a text for which she’s keen to find a publisher. I asked her about the relationship she sees between her writing and her moving image work, which is often more corporeally based. She explains, “I trained in creative arts, majoring in writing, contemporary visual art and theory—so that’s very much how I approach my work, through these intersecting mediums. I think what I’ve always done is begin with a conceptual or philosophical idea and use my practice as a way of exploring that through a form that isn’t language, because you can’t do everything with writing…[then] I write about that at the end [of the process], in this ficto-critical way where I’m using the story of my experience of making the work to talk about how it’s changed or extended the conceptual idea or theoretical idea that I’ve been thinking about.”

Sarah-Mace Dennis, Swallow (currently in development)

courtesy the artist

Sarah-Mace Dennis, Swallow (currently in development)

Art and social responsibilities

As well as Swallow, Dennis is working on a large-scale video project, Do you protest in silence?, which indicates a shift of focus from historical to contemporary social reflection. Through her experiences making Sounds from the Emergent State, Dennis has become increasingly interested in how music and art inspire social change. She has recently moved to London via New York where she met up with filmmaker Antonino D’Ambrosio whose recent documentary Let Fury have the Hour explores how artists can elicit “creative responses” from people that dramatically effect culture as a whole. Dennis hopes to continue her dialogue with D’Ambrosio as she works on her video project.

In a follow-up email Sarah-Mace Dennis writes, “I think being outside of Australia has been quite important. Being in a new place has given me more courage to find my voice on bigger issues that affect the world on a global level… [Do you protest in silence?] is still about consciousness and the brain, but it is also about how creative ideas really have the potential to affect the way we think about and live in the world.”