Inside the real/digital warp

In 1998, when it seemed like it was just beginning, tech visionary Nicholas Negroponte declared the digital revolution over. This did not mean the end of computational technology, but that in the networked world it had become so pervasive as to cease being remarkable. Perceptions toward technologies had changed as the digital infiltrated so many aspects of everyday life. Since then there has been an increasing intermingling of digital and analogue and tentacle-like extension of the digital into realms beyond the screen. Amy Marjoram, curator of the Warp exhibition at Fremantle Arts Centre, observes some of the effects of this entanglement, writing in the exhibition catalogue, “When we exist so much online, trace residue from this existence is everywhere in our lives.”

Certain pundits describe this condition as “post-digital.” Just as postmodernism was perceived as being not about the absence of modernity, but rather a continuation and splintering of its effects, the post-digital is a reconciling of the effects of the digital with the existing world. Attendant to this, and especially in the arts, is an increasing drive to humanise technologies, a concern with being human in a networked world with technology as integral. Echoing such ideas in the curation of Warp, Marjoram writes, “This exhibition is about the cohabitation of the digital and physical realms, and the reality and mirages within both.” As part of the 20th anniversary of the Revelation Perth International Film Festival, Warp tackles our digital present with works that engage with the complexities of its manifestations, from the mundane to the provocative.

Call of the Wild, 2013, Michael Meneghetti, WARP, Fremantle Arts Centre, photo Jessica Wyld

Across two rooms and a corridor, Warp presents new video works by four Western Australian and four Victorian artists. The first room is dominated by a large scale projection by Michael Meneghetti (VIC) titled Chiamata del Selvaggio/Call of the Wild (2017). Like an awkward seal at the edge of the water, a person clad in a head-to-toe black wetsuit with flippers, flops along a seaside. If not an earnest grasp at transhuman embodiment, this absurd scene is certainly reminiscent of the bizarre expressions of humanity that you might stumble across in online fetish videos.

At the opposite end of the room is Constant Elation (2017) by Tom Blake (WA). A sheer curtain cordons off part of the wall on which videos are screened on a cluster of mobile phones. The scenes playing out all revolve around the theme of plane travel: red wine quivering in a plastic cup, the shadow of a plane glimpsed on the ground, views outside the window and the suggestion of states of jet lag. Over the course of the day the screens gradually die off as phone battery life is exhausted. This is part of the work, a commentary on the tenuousness of mobile technologies, their failings.

Lou Hubbard (VIC) has a curious work in this room titled Tap Me (2008). An elderly woman lady sings in dulcet tones but all we see is her finger repeatedly tapping a touch-sensitive lamp and changing its output. This simple and somehow melancholic gesture is loaded with meanings. It speaks of a gaping generational divide and the reality that for digital natives this gesture is immediately associated with repetitively and mindlessly tapping through screen content.

Video still, Hospital Landscapes, Georgie Mattingley, WARP, courtesy the artist and Fremantle Arts Centre

Part of the lure of the digital is its ability to infinitely distract; beyond fleshy reality precious time dissolves into screens. This idea is implied on a monitor in the hallway screening Georgie Mattingley’s Hospital Landscapes (VIC, 2016). It cycles through still images of paradisiacal scenes as wall murals or on posters in otherwise clinical hospital environments. These landscapes are meaningless distractions like so many of the superficialities encountered online. They silently rupture the homogeneity of the sanitised space, but belie this aim by simply fading into the background, as unremarkable.

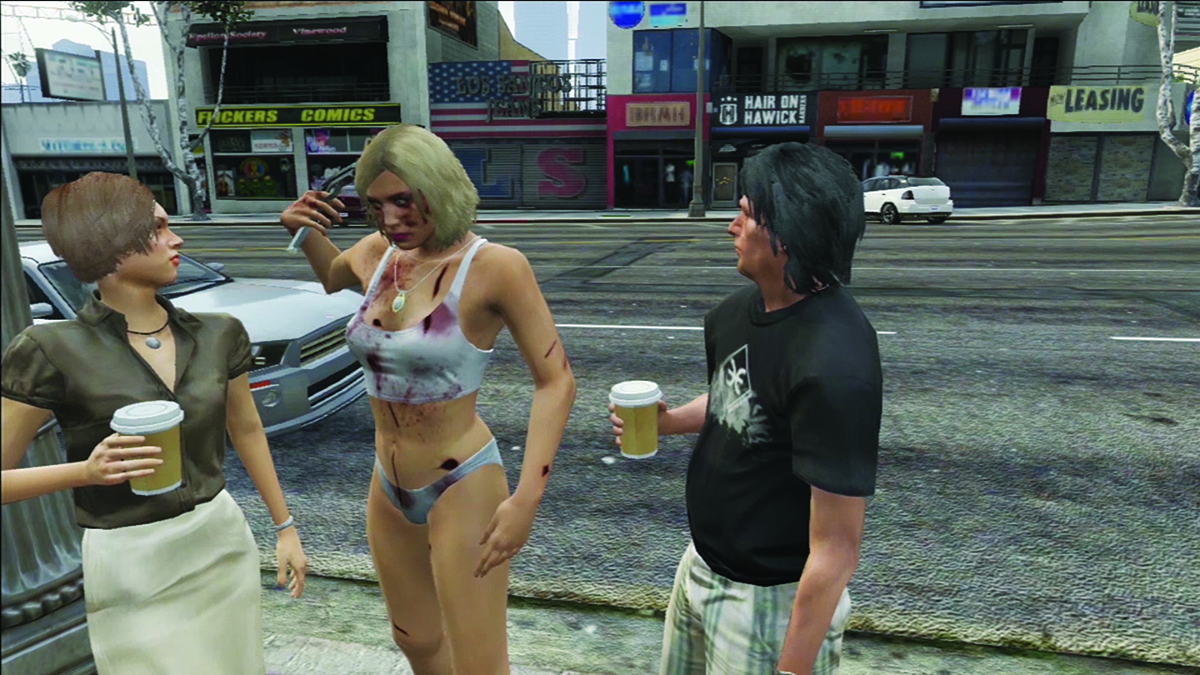

The next room is an auditory assault with the sound of a gun being fired ad nauseum. The source is 99 Problems (WASTED) (2014) by Georgie Roxby Smith (VIC). In an online video game intervention into Grand Theft Auto V, a bikini-clad, blood splattered female avatar repeatedly shoots herself in the head in various urban contexts. Marjoram writes that this exhibition will “gently puncture the apparent seamlessness of the networked world,” and while this piece presents a violent puncture in otherwise calm game moments, it is also self-referential to the genre and its gratuitous violence.

99 Problems (WASTED), 2014, Georgie Roxby Smith, WARP, courtesy the artist and Fremantle Arts Centre

It’s a relief, perhaps, to turn to Andrew Varano’s Tracking Shot (Autumn) (WA, 2017). At the end of two parallel bench seats is a screen on the floor, angled upwards and displaying a tracking shot of the ceiling of a room from the perspective of the floor. The camera pans, showing us a lighting track and the underside of couches. This is like a portal into the domestic space beyond the screen and we are reminded of the bench seats on which we sit, embodied.

A similar perspective is granted in Dale Buckley’s From where you’d rather be (WA, 2017). Here the camera gazes up at and smoothly pans along tree foliage; only the vision is filtered and crunchy. It is as though we are granted robot vision and this recalls early computer scientist Alan Turing’s suggestion that artificial intelligence could develop from robots roaming the countryside and learning from the physical environment.

Aptly then, Ellen Broadhurst (WA) suggests the spill of the digital into the physical, or their post-digital hybridisation, in two works where videos are embedded within vomitus, bulging landscapes of expanding foam. In John Oldham’s Phony Waterfall (2016) a log plinth contains the foamy landscape, embellishing it with artificial fern foliage. On the screen we see washed out footage of a hidden waterfall in John Oldham Park in inner city Perth. There’s a suggestion here of a loss of the real; a phony creature swims in the water and although it’s in a real place, it is also housed within an entirely artificial landscape.

In “What is Post-Digital?” media theorist Florian Cramer argues that the post-digital “refers to a state in which the disruption brought upon by digital information technology has already occurred.” Warp makes it look as though we are caught up in the aftermath of this disruption, in tentacles of the digital in a kind of eternal return, like the avatar who keeps shooting herself and coming back, there is no escape.

–

Warp, curator Amy Marjoram, artists Tom Blake, Ellen Broadhurst, Dale Buckley, Lou Hubbard, Georgie Mattingley, Michael Meneghetti, Georgie Roxby Smith, Andrew Varano; Fremantle Arts Centre, 27 May-16 July

Top image credit: Video still, The Ship That Never Sank, 2017, Ellen Broadhurst, WARP, Fremantle Arts Centre