Cinesonics (1997-2001): Viscerally performative

If memory serves me correctly, it was Alessio Cavallaro [co-editor with Annemarie Jonson of the OnScreen supplement] who approached me to write something for RealTime on soundtracks. I had known Alessio since the early 80s through his key involvement in Sydney currents of experimental music through his 2MBS-FM radio show, releases and events. He effectively brokered my entry into RealTime, and I was warmly welcomed by Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter.

At that early stage, RealTime – in my view — was not something I would have considered for two reasons. One, it was very strong on its coverage and writing on the live performative arts; and two, its adoption of a transformed Filmnews in the guise of its OnScreen section. Throughout the 80s, my critical interests in cinema and music had led me to find various niches, nooks and crannies for publishing articles, running a synchronous though far less rigorous line engineered by my colleague Adrian Martin. While Adrian occasionally published sharp and incisive critical pieces in Filmnews, I had mostly found that newspaper’s writing socio-politically oriented, and somewhat defensive and divisive in its support of Australian independent filmmaking.

My view then (as now) was that the cultural binaries which hold ‘independent’ and ‘mainstream’ in place forge segregational liabilities in fostering a deeper understanding of the complex ambiguities, contradictions and simultaneities which make film culture a fascinating mess. Having had no connection with the 70s counter-cultural avenues which created and nurtured ‘Australian independent filmmaking’ (the film co-ops, government lobbying, distribution networks, etc), I shared few of its values or ideals – which were intoned through much of what I regarded as an anti-intellectual bias in Filmnews. Maybe it worked well for originating filmmakers with those values and ideals, with Filmnews operating as a galvanising newspaper for a community of like-minded artists, but it simply wasn’t for me. When I made Salt Saliva Sperm & Sweat in 1988, the film inevitably flowed through the paper’s channels and was critiqued not as something different and alternative, but as something wrong and unwarranted. All I did was make a film which demonstrated one of a million ways in which one could produce ‘Australian independent filmmaking.’ Its reception in those quarters reinforced my views of that context: when writing pays lip-service to ideology rather than the cultural object at hand, the velocity of ideas withers.

Sooooo, when Filmnews transitioned into the RealTime’s OnScreen, I would have to admit that while comprehending the importance of creating a communal/industry organ for independent filmmaking was important for its practitioners, I still found the critical writing lacking in breadth, flexibility and case-by-case evaluations which could augur a rethink of ideological mandates on ‘Australian independent filmmaking.’ Counter to my prejudices, broader and tangential currents of film cultural discourse gradually seeped into OnScreen, and in this softening of didacticism I assume Alessio saw the opportunity for it to encompass what by the 90s had become numerous tentacles of media intervention, artistic reformulation and critical practices to do with ‘the moving image.’ With a strong background in audio arts, Alessio tagged me as someone to bring some noise to the proceedings.

Film as experienced, in the cinema

Superficially, the articles for Cinesonics were directed toward surround-sound production done for feature films, evaluated as experienced in cinemas. But the articles were also inevitably contextualised by (a) the state of this thing called cinema at that millennial point in time, and (b) how critical rigour could be applied to theorising ways in which sound/image, music/narrative, psychoacoustics/character and other audio-visual compounds were being developed in current films of all stripes. Like unpacking a matryoshka doll, there was always something else rattling inside any element I analysed. Sitting in the auditorium, I would be excited by some sonic or aural moment in the film, but when I returned that night to write the article, I found I would have to laboriously contextualise why that moment was noteworthy.

A shattering crash in The Haunting (RT33); a drone of nothingness in Lost Highway (RT19); Eddie Murphy interacting with composited/post-dubbed stand-up lines in Doctor Doolittle (RT26); the absence of music and the roar of air-conditioning in Contact (RT24); New Orleans Gothic swamp funk in Michael Jackson’s GHOSTS (RT20); the aural hormonal bombast of teen energy in Bring It On (RT41). Each of these moments — lived in the present while auditing the films — was like a lock to comprehending the what, how and why of the film soundtrack’s greater potential. But each sentence I wrote was snared by assumptions that I was somehow addressing notions of ‘the film industry,’ ‘quality movie-making,’ ‘professional craftsmanship,’ ‘technical standards in mixing,’ ‘good film music’ and so on. In attempting to address cinema at its most experiential moment of occurrence, I was confronted with the overwhelming thrill of matching my chosen film analysis with how cinema was forming itself then and there. The Cinesonics articles were exploded diagrams of these theoretical matryoshka dolls — and their wooden box, the bubble wrap, the cardboard package, and the way it had all been damaged in transit.

Neon Genesis Evangelion

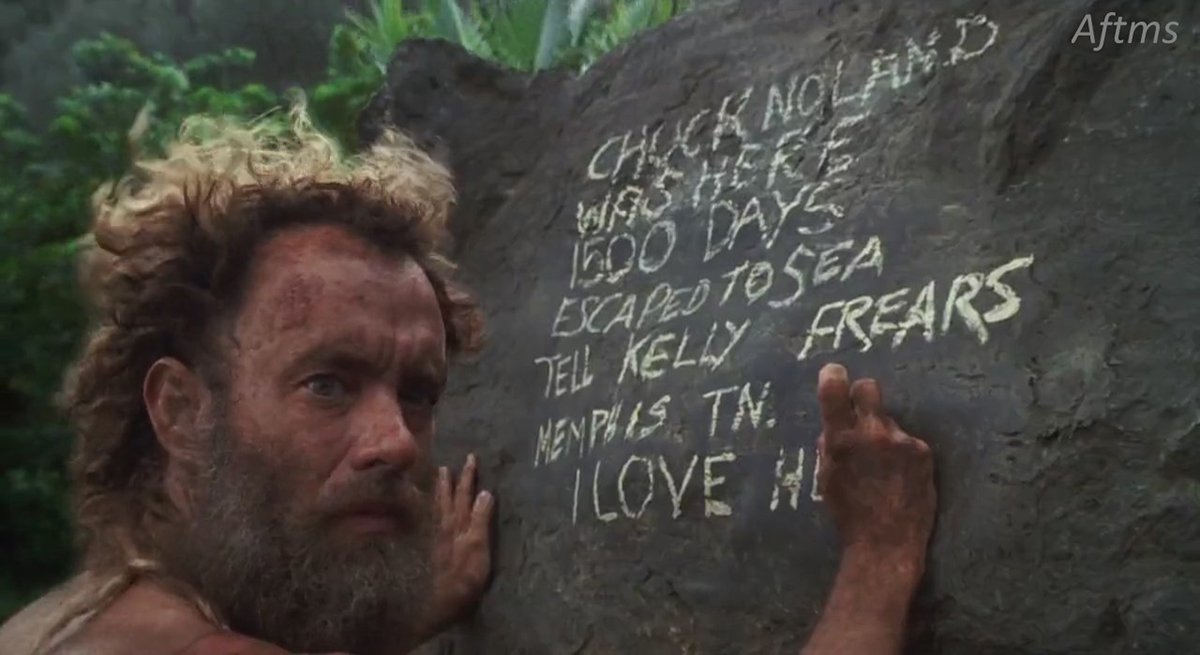

When I took leave of writing the column after 21 articles, I remember Keith Gallasch joking he would miss having to watch all the awful movies I wrote about. True, I wrote a lot about awful movies — but mainly to evidence how their sound design, song selection/placement and composed film score gave momentum to the repressive and limiting measures embraced by both bland industry acolytes and prissy arthouse proselytisers. This is why I mauled the audio-visual flaccidity of Lost In Space (RT25), Armageddon (RT27), Doctor Doolittle (RT26), The Truman Show (RT28), Virgin Suicides (RT39) and Run Lola Run (RT32). For the same reason, I pored over the sono-musical complexity of Lost Highway (RT19), Contact (RT24), Neon Genesis Evangelion (RT31), Magnolia (RT 36 and RT 37), I Stand Alone (RT32), The Straight Story (RT38), Bring It On (RT41), Cast Away (RT42) and Crazy (RT43).

Tom Hanks, Cast Away (2000)

Indeed, a running thread through the articles traces an aversion to condescending humanist proclamation, bordered by an attraction to post-humanist sonority and musicality. The more a movie asserted its hand-wringing, globalised anguish or fluffed-up its poeticised, narcissistic moralism, the more disdain I coughed onto its whimpering candle. The more a movie moved past humancentric posturing and patronising concern for ‘the world,’ the more I fanned the flames of its meta-discourse of non-holistic characterisation, conflicted ethics, ambivalent tone and psychological displacement. Why? Because while so much of the supposedly ‘informed/committed arts’ aspire to the latter, they end up too often voguing PC altruisms against a backdrop of naive utopian wishfulness. Personally, I don’t care at all how pathetically humanist and self-centred films like Armageddon and The Truman Show are, or whether such films continue to be made. I am more concerned when half-baked ‘art’ — as in ‘arthouse cinema’ purportedly opposed to ‘Hollywood fodder’ — replicates the same sappy greeting card sensibilities.

Yeah, but even when I think about it, this approach smacks of its own moralism. Fortunately, RealTime overlooked these infractions of authorial solidity. Keith and Virginia would usually query me over a lava stream of literary vitriol and request better justification for my assertion. This was always appreciated, because the core aim of Cinesonics was to be ‘hyper material’: each and every assertion had to be qualified by an adequate description of how the soundtrack materialised the moment under scrutiny. Prior to hitting the send button for each submission, I would often open the article and randomly highlight a small section of the text: whatever I picked had to have verbs and nouns strictly associated with describing sonic and aural phenomena. (I just tried it on some of the articles. It still works.)

Magnolia (1999)

Real time writing

The Cinesonics articles were written usually a few hours after seeing/hearing the film in the cinema, and were drafted to capture the isolated, episodic or continual flow of the film soundtrack’s eventfulness. On reflection, it makes sense that RealTime — with its roots in the performative arts — welcomed this approach to critical ‘real time’ writing on the cinema. I can’t think of any other film-related publication — then, before or now; indie, alt, industry or mainstream — that would get what I was after with this approach. I don’t care whether the Australian film industry and the various government, departmental, officiated, privatised, gonzo, alternative, advocated, sharing or streaming tentacles of its ‘moving image culture’ wither and die. I’ll always find some speaker cable in its viscera. I’ll hook it up to a sea-soaked battery and connect it to my pelvic bone. And I’ll still find plenty of cinesonic moments to thrill me.

In some fact-checking for this reminiscence, I stumbled across this:

“The relationship between sound and image in film has always presented filmmaking with interesting effects and problems. Probably the most primary source of textual conflict (where conflict generates meaning) is the sound/image relationship: an inexhaustible dichotomy in the construction of a film text. (…) The sound and image texts feed and feed off each other. Through modes of deconstruction, these texts can be dislocated, scattering the meanings contained within them.”

That’s me, 21 years old in 1981, writing a program note for my Super 8 film The Opening Ceremony Of The 1980 Moscow Olympics As Televised By HSV Channel 7. If I thought I’d changed much over the years, it seems I really haven’t. And if you don’t share my formative values and ideals (Count Yorga Vampire, Iggy Pop’s The Idiot, Roland Barthes’ S/Z, Straub & Huillet’s Othon, Lipps Inc.’s Funky Town) then feel free to dismiss all you just read – and start something new.

–

See also “Move fast and hear things: writing Audiovision,” Philip Brophy’s reflections on writing his 2015-17 column for RealTime.

Top image credit: Patricia Arquette, Bill Pullman, Lost Highway (1997)