Joseph Mitchell, interview, OzAsia: Epically Personal

If there has ever been a necessary moment for Australians to be ‘taken out of ourselves,’ to evaluate our cultural and political place in the world as geopolitical tectonic plates shift us away from the US, it is now. Once ‘outside’ we can open up to and appreciate cultures substantially different from our own, look back at ourselves and acknowledge the art growing here that tells us how Asian-Australian our culture has become, alongside and entwined with our European and Indigenous heritages. With an intensive program, at once accessible and provocative, Adelaide’s annual OzAsia Festival continues to temporarily relocate and enduringly reshape our collective imagination with intensive and seductive programming.

When we meet in Sydney prior to the launch of the 2017 program, I ask OzAsia’s Artistic Director Joseph Mitchell about the progression of his programming over his three festivals since 2015. He tells me that after “breaking down the fourth wall” with immersive contemporary Asian works (including visual and performance art) in his first festival, in his second he focused on works that commented on their countries of origin (including the strange cultural and economic relations between America, Japan and Korea in Toshiki Okada’s wonderfully absurdist God Bless Baseball), “along with a brushstroke picture of the city/rural divide” (as in the wildly funny and socially critical Chinese production Two Dogs, an exemplar of the merging of traditional and modern popular performance).

In his third festival, Mitchell says he’s “going in deeper with a large focus on very personal and intimate stories told from Asia and with more Asian-Australian collaborations, in the arcs of dance as well as in theatre.” As our conversation continues, it becomes clear that the ‘personal’ will be framed within mythology, history and gender as will a focus on artists who are setting the agenda for furthering 21st century Asian and global culture.

Next week we’ll survey collaborative Australian and other works in the festival’s program and, shortly after, the visual arts component. This week Mitchell and I focus on the major theatre and music components.

Until the Lions, Akram Khan Company, photo Jean Louis Fernandez courtesy OzAsia 2017

Akram Khan Company, Until the Lions

At first glance, British choreographer Akram Khan’s acclaimed Until the Lions, a dance adaptation of a story from the Mahabharata, seems an unlikely ‘personal’ tale. Mitchell explains, “It is a big work, with a big set, but it’s a particularly individual story. The creators, Khan and poet Karthika Nair, have focused on a story they convey from a female perspective about a princess, Amba, who is abducted by a general, Bheeshma, and she seeks venegeance.” Nair had gathered stories about often unacknowledged female characters from the Mahabharata in her book of poems Until the Lions, which became the title of her collaboration with Khan. In an unusual twist, Amba kills herself, is reborn and changes gender to defeat Bheeshma. Nair has explained the title: it’s based on an African saying about who gets to tell the story after the hunt — usually the hunter; but the tale is not properly told until the lions speak; as it should be for the women in the male-dominated Mahabharata.

Although British reviewers have praised the work for its adroit abstraction and use of symbolism, Mitchell says, “dance theatre is such a loose term, but Until the Lions is a narrative told through dance in 55 minutes. “As with a play, “you need to watch and decode to understand.” A YouTube trailer offers glimpses of an engaging blend of the literal and its abstraction, particularly in fight scenes.

Recalling Mother

Mitchell describes Recalling Mother as conversational performance but also as another very physically expressive work. Singaporeans Claire Wong and Noorlinah Mohamed are friends who explore their relationships with their non-English speaking Cantonese and Malay mothers, taking turns to play each other’s mother in mother-daughter dialogues. Mitchell tells me that when the work was first performed almost 12 years ago, the emphasis was on comedy and the language and culture-clash tensions “between tradition and Singapore’s slightly hybridised Western identity. The humour is still there, but the artists don’t remount the play so much as recreate it now that one of the mothers has dementia and the role of carer and a sense of mortality have entered and intensified the sentiment. The show runs for 75 minutes but with a Q&A which the artists see as part of it, because they feel audience members need to debrief about their own relationships with their mothers.”

In an interview, Noorlinah Mohamed said of Recalling Mother, “It is perhaps the first and only theatrical project, that when restaged, is always revisited as a new creation. The work is a living durational performance where life and art parallel and inform each other.”

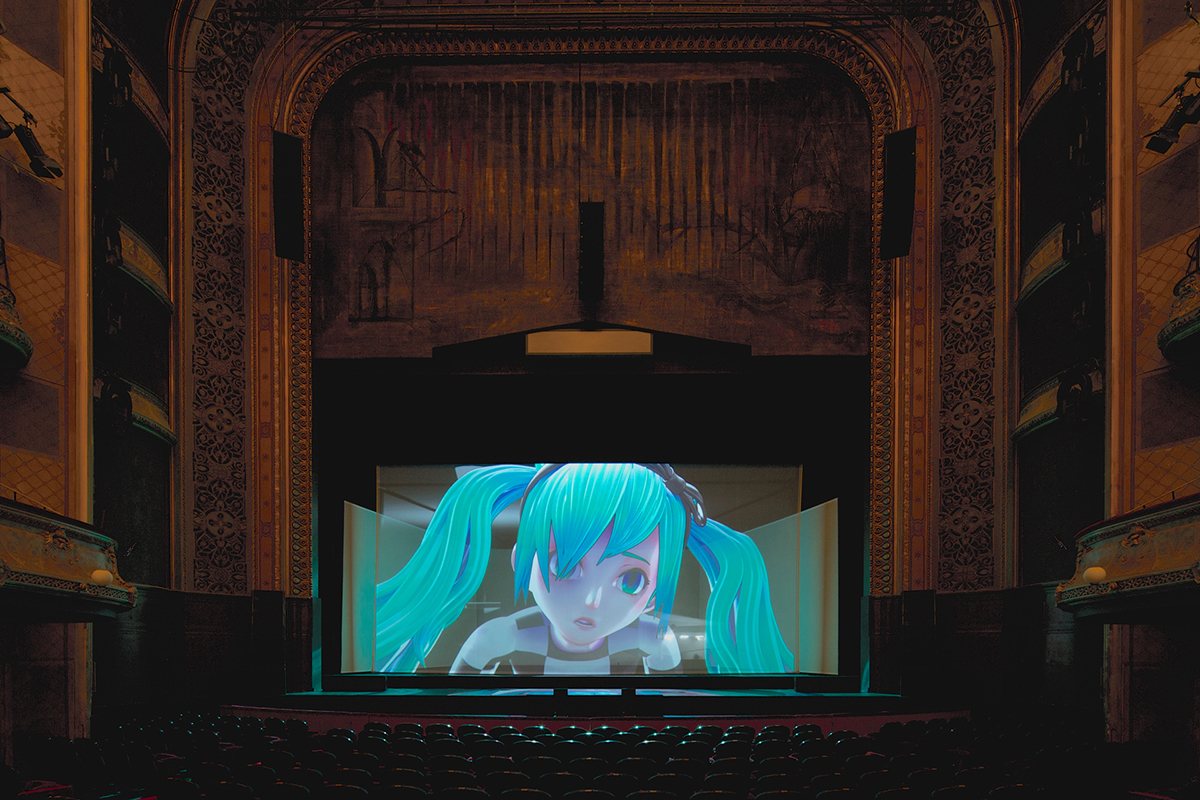

The End, Keiichiro Shibuya + Hatsune Miku, photo Kenshu Shintsubo courtesy OzAsia 2017

Keiichiro Shibuya + Hatsune Miku, Vocaloid Opera: The End

The sense of the personal might seem to evaporate when contemplating two works by a Japanese artist which feature non-human performers: one with a vocaloid (think singer + android) and a robot. Of Asian artists setting the agenda in performance, Mitchell sees Japan’s Keiichiro Shibuya, “with his bold sense of provocation,” as the standout exemplar. He has created The End, an opera for theatre without live singers or an orchestra for virtual pop idol Hatsune Miku. Mitchell says, “she is one of the biggest pop stars in the world. She has some 100,000 pop songs about teen love and relationship breakups, composed by professional teams but also by hardcore fans via purchased software. Shibuya had been a fan and when his wife, a leading fashion designer, died and he spiralled into depression, he latched onto thinking about the nature of death and how Miku will never die. He thought, ‘What if I go into her psyche and find out who this vocaloid is, loved by the world?’ So he asked the novelist, playwright and Artistic Director of chelfitsch, Toshiki Okada, to write the libretto and approached Louis Vuitton to design Miku’s outfits for a giant opera. It’s the most elaborate of her set-ups for an appearance and involves four screens and a mini-screen behind which Shibuya plays the music live.”

Mitchell notes that “When The End debuted Miku’s fans turned out: they were nervous, keen to support her doing opera, hoping she’d last the distance, but had faith in her and were very excited to see her dressed by Vuitton. It went to Europe last year, a bit outside her realm, but created a fusion of arts lovers and fans.” He does believe The End “has to be a dividing piece in terms of the operatic voice. However, the score and the libretto have all the hallmarks of great operatic tragedy and self-insight. At a time of the Australian Government review of opera, a decline in audience numbers and the large cost of the subsidy involved, we need to think about the artform and let it evolve; this work points a way.”

Skeleton, Ishiguro Lab, Osaka University, photo Justine Emard, courtesy OsAsia 2017

Australian Art Orchestra: Keiichiro Shibuya, Scary Beauty

Shibuya makes another appearance in OzAsia 2017 with Scary Beauty, again with a non-human performer — Skeleton, a singing robot with its own neural network — and, again, imagined as a large-scale work. But, says Mitchell, that would have taken years to develop, so the artist was commissioned to present a version of the work with the incisively adventurous Australian Art Orchestra, led by Peter Knight, as part of an afternoon of three discrete concerts featuring Shibuya, guzheng player Mindy Weng Wang and, in Seoul Meets Arnhem Land, Ecstatic Beauty, the pairing of Korean ‘street opera’ singer Bae Il Dong and Daniel Wilfred from the Wagilak clan in the Northern Territory.

Joseph Mitchell sees a widespread preoccupation with robots as workers and service providers as ignoring the rise of AI, which demands of us a better sense of what it is to be human; that, he thinks, can come through art and the challenges offered by works like Skeleton. This cluster of concerts should be a festival highlight, invoking living heritage and evoking possible futures.

Hotel, W!ld Rice, photo courtesy OzAsia 2017

W!LD RICE, Hotel

The personal is given an epic dimension in W!LD RICE’s Hotel, 100 years of Singapore’s history performed over five hours. Mitchell describes himself as a slow decision-maker, but within minutes of seeing Hotel he knew he had to program it: “We have to do this, no matter what. It’s one of the best theatre works I’ve seen in the last few years and has never had a bad review. You can see it all at once or in parts and is a bit like watching a Netflix series — there are 11 stories of some 20 minutes each, with characters and incidents overlapping, characters ageing across 40 to 50 years and told through the lives of ordinary people — from British colonialism to the Japanese occupation, independence and the explosion of today’s queer culture.” The hotel is unnamed, but it’s easy to guess it’s Raffles and all that it has symbolised. Mitchell feels that, like Australia’s widely played Secret River, Hotel is a story that needs to be told. Read more about Hotel, Mitchell’s first large scale work for OzAsia, here.

Niwa Gekidan Penino, The Dark Inn

Although enamoured of earlier works by Kuro Tanino and determined to program him in OzAsia, the auteur’s most recent work, The Dark Inn, proved to be Mitchell’s ideal choice. “The early work was really ‘out there.’ Kuro’s a trained psychiatrist who has worked with a lot of people who don’t see the world the way we do, so he created theatre from their viewpoint. The sets were crazy, with strange dimensions: there were penises across the stage. I saw The Dark Inn in Kyoto last year and agree with people who think this is Kuro’s masterpiece. It won the Kishida Prize for Drama.

“A dwarf father and his tall son are travelling puppeteers booked to play in a country bathhouse but arrive to find a disparate bunch of characters who are not expecting them. In the kind of revolving, multi-level set Kuro’s famous for, with a Japanese bath, steam, inquisitive characters and odd conversations, the play is more about inner states of mind than a straight narrative.” Mitchell adds, “After appearing in major US and European festivals, this is Kuro’s first visit to Australia and is a great opportunity for audiences and those attending the Australian Theatre Forum during OzAsia to see new directions offered by this kind of work.”

Darlane Litaay, Tian Rotteveel, Specific Places Need Specific Dances, photo courtesy Indonesian Dance Festival & OzAsia 2017

Specific Places Need Specific Dances

The collaborative dance work Specific Places Need Specific Dances foregrounds personal desire. Darlane Litaay from Papua New Guinea and Tian Rotteveel from Germany, investigate “waiting in different places, sharing culture and exchanging daily habits” (program). Each visits the other’s home country out of curiosity, says Mitchell, “Darlane to experience Berlin’s underground club and dance scene, Tian to see traditional male garb and in particular the penis horn. To Western eyes, these can appear sexual and as empowering the male figure. There are readings you can take from this work about exchange, sexuality, queer culture and male identity. For me, this is a work which sits at the cutting edge of contemporary dance.” Two more artists, in their Adelaide premieres, confirm Mitchell’s commitment to dance that draws on tradition and local cultures while venturing in new directions.

Aakash Odedra Company, Rising

Aakash Odedra will perform a self-choreographed contemporary Kathak piece and works made for him by Akram Khan, Russell Maliphant and Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. Maggi Philips wrote of the performance at the 2015 Perth Festival, “Odedra’s presence and collaboration with an impressive list of contemporary choreographers delivered a sense of celebration awakened in a performance which gathered strength from tradition and experimentation alike, yet was humble and projected humankind as simply strange and remarkable in a world of mystery, beauty and pain.”

Eisa Jocson, Macho Dancer

Eisa Jocson, who has appeared in Performance Space’s Liveworks in Sydney and Melbourne’s Asia TOPA, performs her eerie, gender-bending solo work Macho Dancer, drawn from her personal observations of Filipino club dancers. She said in an interview in RealTime, “Macho dancing is performed by young men for both male and female clients. It is an economically motivated language of seduction that employs notions of masculinity as body capital. The language is a display of the glorified and objectified male body as well as a performance of vulnerability and sensitivity.”

I wrote of this striking performance in 2015, “Jocson becomes a young, gum-chewing male dancer passing though a series of telling phases in which he is variously proud, defiant, calculatingly erotic and sulky; at one point he stops dancing and withdraws into upstage shadow — a tease or a moment of existential doubt?”

We’ll tell you more about Joseph Mitchell’s third OzAsia Festival in coming weeks, but already I feel a sense of eager anticipation building around the prospect of entering the idiosyncratic worlds of Akram Khan, Keiichiro Shibuya, Kuro Tonini, W!LD RICE and Darlane Litaay and Tian Rotteveel, with their offers of opportunities to redefine art and self.

–

OzAsia Festival, 2017, Adelaide, 21 Sept-8 Oct

Top image credit: The Dark Inn, Niwa Gekidan Penino, photo Shinsuke Sugino courtesy OzAsia 2017