Vince Gilligan & cable TV, the new arthouse

“Cable television is the new arthouse,” David Lynch said recently, and he if anyone should know. The statement is borne out by the Series Mania festival at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, the first local edition of an event that has run in Paris for years. The packed program featured previews of several brand new Australian TV shows, such as the Melbourne-made Sunshine, set in the South Sudanese community. There’s also much intriguing international content, such as the thrillers Your Honor and Supermax, from Israel and Argentina respectively. First and foremost, however, I’m here to meet the legendary Vince Gilligan ― creator of Breaking Bad, co-creator of Better Call Saul and the festival’s guest of honour.

Of the handful of genuine innovators in current American television, Gilligan may be the hardest to pin down. While he tends to present himself as a straight-up genre storyteller, TV history has seen few hits more unlikely than Breaking Bad, a slow yet grotesquely violent melodrama in which a repressed Albuquerque science teacher deals with his cancer diagnosis by becoming a meth kingpin. Intricately plotted and often unbearably suspenseful, the show also proposed the most corrosive view imaginable of patriarchy and capitalism, whether or not Gilligan and his team gave these abstractions a moment’s conscious thought.

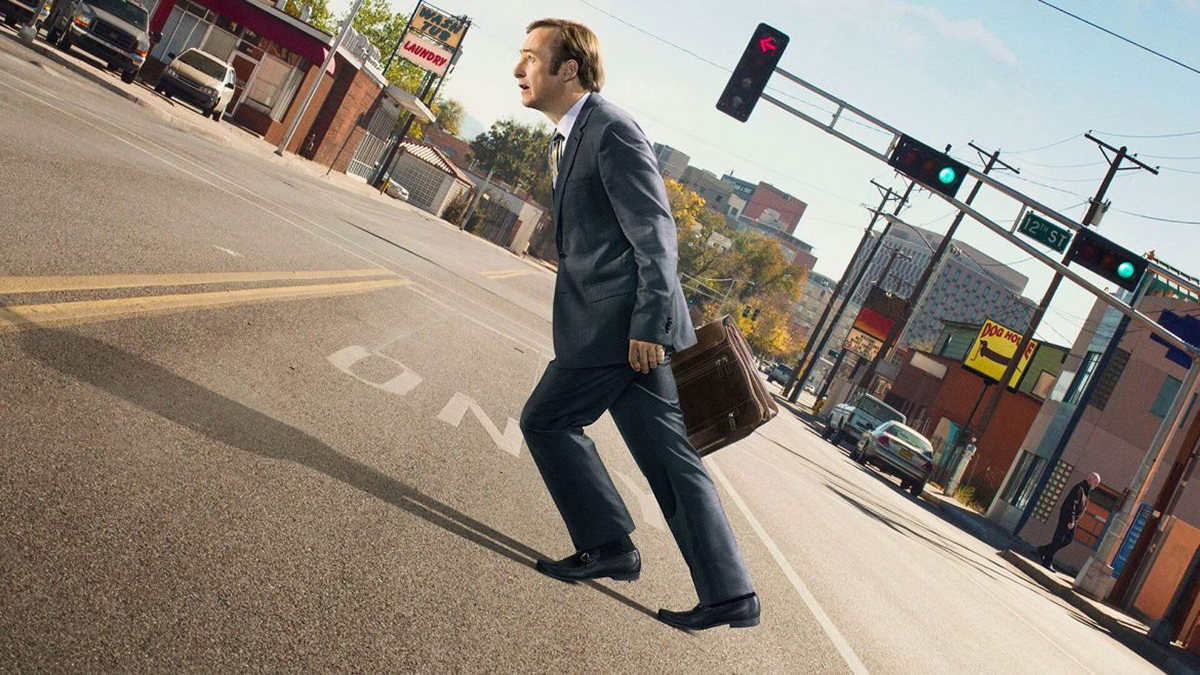

Better Call Saul is closer to art for art’s sake. Having conquered the universe, Gilligan and his collaborator Peter Gould set out to give themselves a treat, plunging into the earlier years of Breaking Bad’s most beloved comic character: shonky lawyer Saul Goodman (Bob Odenkirk), known in his younger days as Jimmy McGill. Like the small-town showman played by Jack Black in Richard Linklater’s great true-crime comedy Bernie (2011), Jimmy is both a folksy hustler and an artist after his own fashion, ruled by an imaginative temperament which impels him to colour outside the lines.

Rhea Seehorn, Bob Odenkirk, Better Call Saul

In truth, Jimmy’s creative and destructive tendencies are impossible to separate: the resulting moral ambiguity lies at the heart of the show, and is only heightened by our knowledge that the character is doomed to devolve into the ruthless dirtbag Saul, who routinely proposes killing people or as he euphemistically puts it, sending them to Belize. In this sense, Saul is as much tragedy as comedy. But is Jimmy solely to blame for his own moral decay, and does he deserve all the suffering he’s in for?

Gilligan’s equivocal reply suggests the question is still in play. “Jimmy McGill is a sweet guy who is a bit of a rascal, but by and large, especially in the early days of Better Call Saul, many of the morally questionable things he does are to help people in need, friends and clients and whatnot. And it’s kind of a shame that he’s going to have to become this calcified individual with a smaller heart, if you will, and someone who does not seem to care as much about doing the right thing, once he becomes Saul Goodman.”

Not that this transformation looks like occurring any time soon. Breaking Bad was known for its deliberate pacing, but Saul pushes this even further, as if testing its ability to create fascination through the mundane. Recent episodes have featured a lengthy set-piece centred on a Bingo game in a retirement home, and a scene in which Jimmy’s fellow lawyer and paramour Kim Wexler (Rhea Seehorn), preparing a legal document, hesitates endlessly between a semi-colon and a full stop.

“We try to have a pretty accurate internal clock,” Gilligan says when asked about the philosophy behind this. “Are things slowed down enough to be even more interesting, because people are used to the opposite? Or at a certain point, is it too slow, so it suddenly becomes dull? I guess the answer is slightly different for each individual viewer, but we try to use that slower pacing, ironically, to increase tension rather than to lessen it.”

Like Breaking Bad before it, Saul is full of enigmatic visual symbols, especially in episodes directed by Gilligan himself. The grid patterns that recur from shot to shot could represent either Jimmy’s chequered moral nature or the cramped spaces, physical and spiritual, in which he’s forced to function. Gilligan, however, is having none of it. “I’m not sure I was aware of that,” he says politely. “I’m going to look for that now. I mean, we’re always looking for interesting framing, and maybe that grid pattern is something that subconsciously appeals to us.”

Bob Odenkirk, Better Call Saul

Not much more emerges when I try to find out if any novelists have influenced Gilligan’s approach to storytelling, given his pioneering use of multiple seasons of TV to tell a single story with a beginning, middle and end. “Well, I hear a lot about Charles Dickens,” he starts out, before admitting that he’s read only A Christmas Carol. “I need to read more Dickens,” he muses. “Such a wonderful writer, and one that I am woefully not as well-versed in as I should be.”

Before meeting him, I’d imagined Gilligan as a version of Kim, a perfectionist who agonises over details. In the flesh, he’s more like another character from the Breaking Bad universe, the criminal mastermind Gus Fring (Giancarlo Esposito), maintaining an air of calm courtesy while preserving his secrets. The closest he gets to personal revelation is when I ask about his collaboration with Gould, and if the pair have different strengths. “He’s much more of a grown-up than I am,” Gilligan says. “He’s not as emotionally volatile as I am capable of being, and I think that’s a good thing.”

The volatility may not be obvious on the surface, but Gilligan’s advice for Australian TV makers could only come from an artist of stubbornly individual temperament. “Take a look around, see what everyone else is doing, and go in the opposite direction. That is advice, I think, that works in any country, in any culture.” Rules, in other words, are made to be broken ― even, perhaps, in Belize.

–

Series Mania, Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne, 20-24 July

Special thanks to Imogen Craddock Kandel and Katrina Sedgwick.

Top image credit: Bob Odenkirk, Peter Gould and Vince Gilligan on set of Better Call Saul, photo Jacob Lewis/AMC