VR at MIFF: A World Apart

The virtual reality packages at this year’s Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF) were everything the rest of the festival wasn’t. For a start, there were no queues around the block to get into the venue — in fact there was no queue at all. Eight of us in the session I attended assembled in a nondescript office foyer in Melbourne’s CBD, from where we were led into a darkened room with a circle of swivel chairs. There was none of the shared anticipation of a big festival event. Instead, we simply sat down, donned headsets, put on earphones and became immersed in our own, solitary worlds.

There has been much talk in recent years about a looming VR revolution, as technological capabilities, costs, and standardisation of equipment have all reached the point where content producers and funding bodies have begun to pay serious attention to the form. My first encounter with virtual reality was a viewing of Lynette Wallworth’s wonderful Collisions at ACMI earlier this year. That work was based on the recollections of Nyarri Nyarri Morgan, an Aboriginal man who witnessed one of the nuclear tests conducted in the South Australian desert in the 1950s. At the time, he had no idea what he had seen. I emerged from that experience feeling I’d witnessed the future of cinema — or the birth pangs of a whole new medium. After experiencing four additional works at MIFF, however, I’m not so sure VR is quite the radical new form it initially appears — or that it is necessarily effective for storytelling. Collisions worked because it allowed viewers to experience something of Nyarri Nyarri Morgan’s dramatic memory of the nuclear blast and its impact on the surrounding landscape. The rest of the work was a philosophical rumination on this experience, rather than a detailed story. In contrast, three of the four VR works seen at MIFF were very much driven by narrative journeys, and were less effective as a result.

Longing for Wilderness

Longing for Wilderness

First in the package was the three-minute Longing for Wilderness by Marc Zimmermann. It began at pavement level, bitumen stretching in every direction, buildings walling me in. The harsh sound of a car alarm blared in the middle distance. Then, slowly, I started to move. Initially, I was facing the flashing lights of the car emitting the alarm, so the movement carried me backwards, away from the vehicle. As I grew accustomed to the VR environment, I swivelled in my chair to face the direction I was travelling. The buildings around me thinned out as trees replaced brickwork. Overhead a brilliant galaxy of stars became visible as the city lights faded. Eventually I was propelled over a vast canyon, suddenly suspended over a landscape of jagged, snow-capped mountains that plunged steeply into thick forests in valleys below. It felt like an illustration from a child’s fairy tale — that is, it felt wholly unreal. After a few moments of turning this way and that to explore the 360-degree vista, the scene faded to black. Technically impressive, the work felt entirely obvious, the clichéd daydream of an urbanite with no real experience of places beyond humanity’s realm.

Sergeant James

Sergeant James

Moments later I was in the next work — Alexandre Perez’s seven-minute Sergeant James – set in a cramped space topped by wooden boards, surrounded by narrow openings on three sides. Toys spilled out everywhere beyond the enclosed space. It took some time, and a lot of looking around, to realise I was under someone’s bed. A figure entered — glimpsed as a pair of feet — while James, the boy whose room I was in, jumped up and down, bending the boards over my head. When his mother turned on the lights, James said he was worried that someone was under his bed. Telling him not to be silly, mum flicked the lights off. In the darkness, the toys slowly came to life.

The effect was mildly creepy, partly because in the immersive environment you weren’t sure where the next slithering toy snake, or rampaging mechanical locomotive, was going to come from. But again, the scenario simply felt too hackneyed to really be effective. By the time James rolled off his bed, hit the floor and pointed his toy gun directly at me, the reflexive joke felt like it had gone on several minutes too long.

The Extraction

The Extraction

The one Australian work in the selection was Khoa Do and Piers Mussared’s six-minute The Extraction, set in a Melbourne of the near future. Or more precisely, inside an armoured vehicle of the near future. I was in the position of a woman who had just been “extracted” (from what, or from where wasn’t clear), while two guards talked in concerned tones about the blood on my legs. The picture kept flickering, as if the character herself was viewing this world via a screen. There was much shouting as one guard realised the other was an enemy and shot him dead. Moments later the vehicle was attacked, and b-movie zombies ripped open the metal walls. The scenario was confused and, again, horribly clichéd, with the zombies looking more like rejects from a high school Halloween ball than figures of terror.

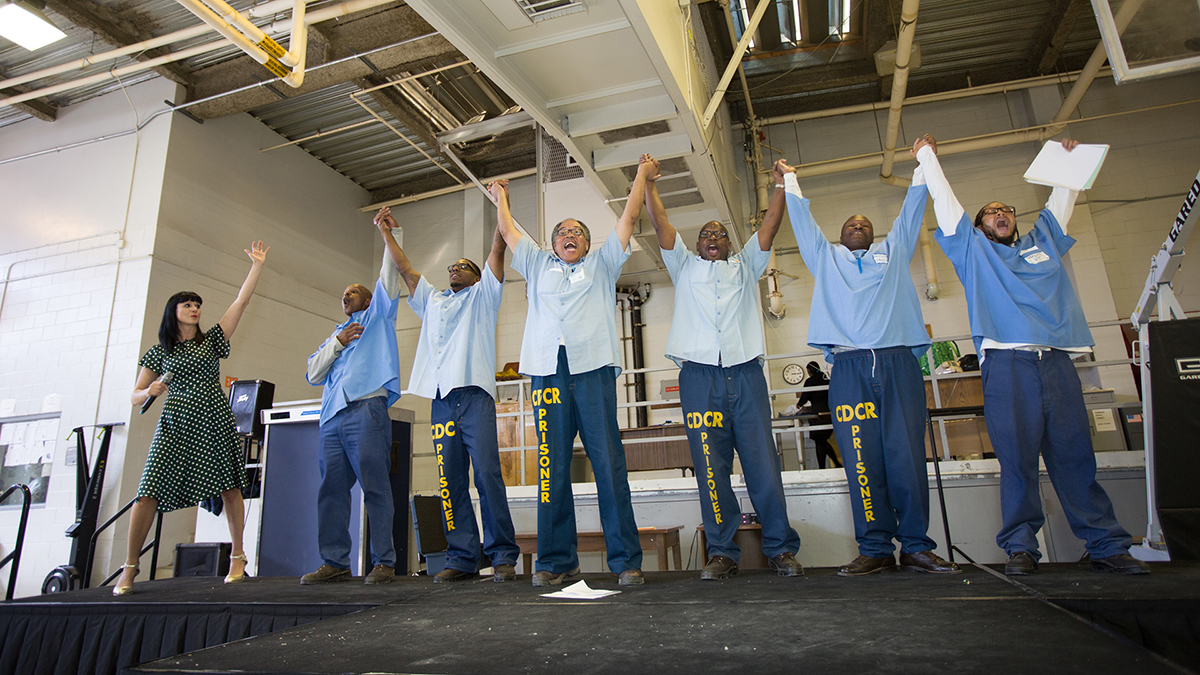

Step to the Line

The only work in the package that attempted to do anything remotely innovative with the VR form was, curiously, also the most conventionally filmic. Ricardo Laganaro’s Step to the Line was a twelve-minute documentary about a rehabilitative program in a maximum security prison in California. A series of jump-cuts took us from the wide-open desert spaces outside, to the close, metallic surrounds of the prison. I was there next to prisoners as they went through their program, privy to their conversations and up close to the soul searching provoked by their experience. I stood beside a prisoner as he recalled being molested as a child by his babysitter, who was herself a teenage mother. Later, the same man discussed the death of his fifteen-year-old son while he was incarcerated, and thus unable to help his boy. In between these conversations, I visited the man’s tiny cell, pressed up against the wall while he stood beside me, looking into my eyes. It was a powerful deployment of the sense of proximity engendered by the VR experience, and a thoughtful confrontation with a world most of us know little about.

The sense of empathetic connection with a foreign environment and its subjects in Step to the Line was powerfully heightened by VR’s immersive qualities. Like Wallworth’s Collisions, Step to the Line used the technology to create a sense of being there, experiencing what others have experienced, rather than attempting to tell a conventional story. Otherwise, it relied on ingredients seen in many effective documentaries – an open, reflective engagement with arresting characters in an unusual situation, and the avoidance of pat solutions to the issues depicted. Conversely, the other VR offerings in the package demonstrated that a cliché is still a cliché, even when virtually rendered.

VR: a world unto itself

Experiencing VR in the midst of a film festival provided a good opportunity to think about the new medium in relation to conventional cinema. When you first put on a headset, VR feels incredibly, almost overwhelmingly “real” – yet watching it alongside more conventional films, it actually felt more like an otherworldly experience. Cinema — or at least a certain kind of cinema — provides a representation of the world we inhabit. VR is a world unto itself, a world that feels quite separate from this one — and this feeling is physical, as well as mental. Having my senses and mind in one place, and my body in another, was quite discomforting after a time and I became nauseous and hot, a feeling intensified by viewing four works in a row. For this reason, I find it hard to imagine long-form VR storytelling being a pleasurable experience.

Telling stories in a 360-degree environment also demands that the viewer’s gaze be strongly directed, while the potentially significant differences in what each viewer sees means that the stories must be based on broad brush strokes and easily recognised generic tropes. This is why the medium works best, I think, when it relies primarily on immersing us in a sensory experience — the witnessing of an atomic bomb test, the inside of a prison — rather than a three-act narrative arc.

VR is also a starkly individualised, almost solipsistic experience. There is sometimes a certain connection with the characters in the VR world, as in Step to the Line. But the nature of this world made it hard, at least for me, to relate these figures back to flesh and blood people. Perhaps my perceptual apparatus is yet to adjust. Or perhaps VR is the quintessential representational technology of our time: disorientating, self-centred, exciting, world-changing — and rife with dissociative potential.

–

VR Package 1, SpACE@Collins, Gear VR Cinema, Melbourne International Film Festival, Melbourne, 3-20 August 2017

Top image credit: Step to the Line