Dawson City: Frozen Time: Twice born of fire

Two things born of fire preoccupy US filmmaker Bill Morrison in his new documentary: a city’s history and cinema itself. Dawson City: Frozen Time (2016) surfaces the archives of the photographs and early silent films from a chilly Canadian Gold Rush town to present a new vision of North American history and myth. The documentary follows Morrison’s earlier works montaged from rescued footage in varying states of decay and after being shown at the New York Film Festival last year, has finally entered the orbit of the Australian festival circuit, which has offered a select but fine collection of essay films this year.

First came Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro (2016) at Sydney Film Festival, which brought to life the words and spirit of James Baldwin to posit that the shame and responsibility for contemporary racism is on white people not black people — that white supremacy is not a blot on the surface of the USA but a brick laid in its foundation and a moral affliction for the dominant culture that makes black people its monster. Then at the same festival came a retrospective screening of For Love Or Money (1983), an almost-lost feminist history of women’s labour in Australia made entirely from archival materials. An exemplary and collectively authored work of the essay film genre, it was all the more striking given the absence of a continuous tradition of that strain of filmmaking in this country.

First Avenue in Dawson City (1898) courtesy of Vancouver Public Library, Dawson City: Frozen Time, courtesy of Hypnotic Pictures and Picture Palace Pictures

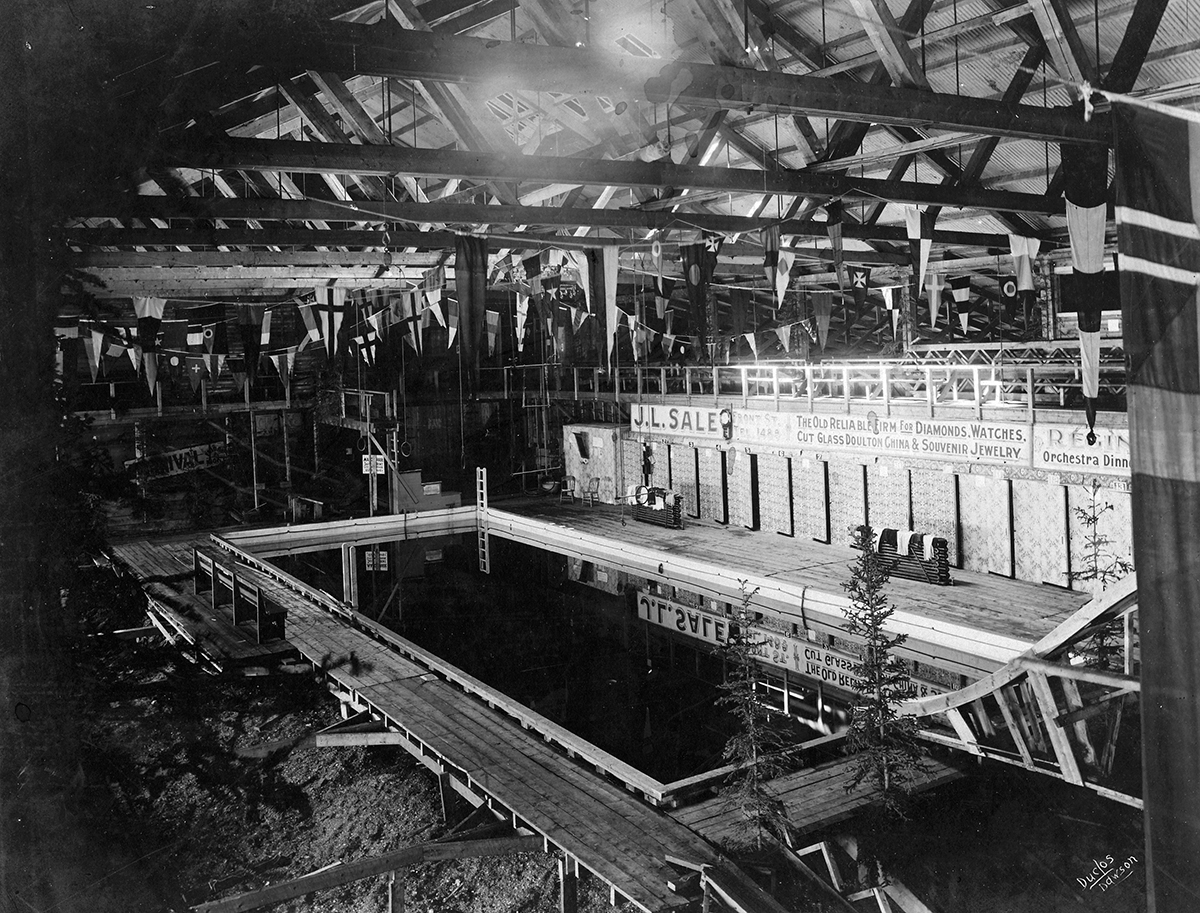

Dawson City: Frozen Time submerges itself in the archive to nudge to other parts of film history: it is in some moments a gold rush drama and in others a Western in the way that it summons an icy frontier, slowly encroached upon by tiny, impoverished, determined settlers. In Yukon, Canada, Dawson City was properly colonised in 1896 and experienced a fever dream of messy capitalist growth spiked by gold mining. For the final years of the 19th century, gold dust was the central currency traded in its brothels, bars and, yes, cinemas. Among the rickety buildings that sprang up in this period were theatres of silent films entertaining exhausted, drunken workers whose families had only just been sent for. Given the town’s remoteness, it lay at the end of the film distribution line: studios refused to pay for the cost of freighting cans of abundant — and dangerous — celluloid film back to California, and the town became a tomb for entertainment industry detritus.

Tonnes of reels past their economic use-by date were stashed in the basements of Dawson City’s frontier buildings, and were liable to burst into flame on account of their highly combustible nitrous base. As such, fire marked the foundations of both the town and early cinema: around once a year, until acetate stock was introduced, a nitrate fire would rip through the streets and colonisation would begin again. Cinema proprietors came to dump film reels by the tonne into the Yukon’s great ice floes: down the river they went, along with archived knowledge of the period’s early silent films.

Over the course of two hours, Dawson City: Frozen Time unfurls a slow-encroaching mystery to reveal the source of the visual material it uses: a self-reflexive discovery of a strange, surely impossible stash of celluloid, preserved in the Yukon permafrost and forever linking the concurrent birth of the gold rush, silent cinema history and the founding myths of this colonial town pitched so perilously in Indigenous snow. Along the way, we learn of Dawson City’s other connections to cinema: the film City of Gold (1957), documenting the Klondike Gold Rush, was the first to use the now-ubiquitous convention of zooming and panning over still photographs, laying the basis for Morrison’s own approach in form and aesthetic as director, writer and editor.

DAAA Swimming pool, courtesy Dawson Museum, Dawson City: Frozen Time, courtesy of Hypnotic Pictures and Picture Palace Pictures

It is of course extraordinary to think of the absence of any notion of cultural heritage in the early days of cinema: that film was so costly to make and transport, but would still be thrown into landfill or a river once its immediate economic value was spent. Nobody thought of keeping cultural objects for posterity. But Dawson City: Frozen Time is much more than a cinephile’s film. Bill Morrison ensures the inhabitancy of the region’s Indigenous people is quietly but tangibly felt, tracking moments in the life and death of Chief Issac of the Han-speaking Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in nation, Mayor of the township of Moosehide, where his people were dislocated, five kilometres downriver as Dawson City ballooned in population. The fragility and waste of the colonial project becomes a ghostly presence throughout the documentary, with overhead photographs later in the film showing how mining has carved the Yukon landscape into gloomy, grey pits of ever-greater scale. The ever-changing geography that cinema crosses becomes a way for Morrison to hint at boundless thematic rivers, depending on what viewers themselves bring to the viewing.

Dawson City: Frozen Time’s most intense quality is its richness, both visually and historically. Every little part of it is inflected with the weight of more than a century of time, every frame full with Morrison’s distilled intentionality. It is a long film, but to spend 120 minutes with it is to be pulled directly into its quiet, largely greyscale world. The flickering, floating footage on which it is almost completely founded, developing from black-and-white to colour, from silence to sound, doesn’t just lend the film its spectral feeling, but writes a new, modest chapter in the much-mythologised story of cinema and frontier America.

–

Dawson City: Frozen Time, director, writer, editor, producer Bill Morrison, producer Madeleine Molyneaux, composer Alex Somers, Melbourne International Film Festival, Kino Cinema, 13 Aug; Sydney Underground Film Festival, Factory Theatre, 17 Sept

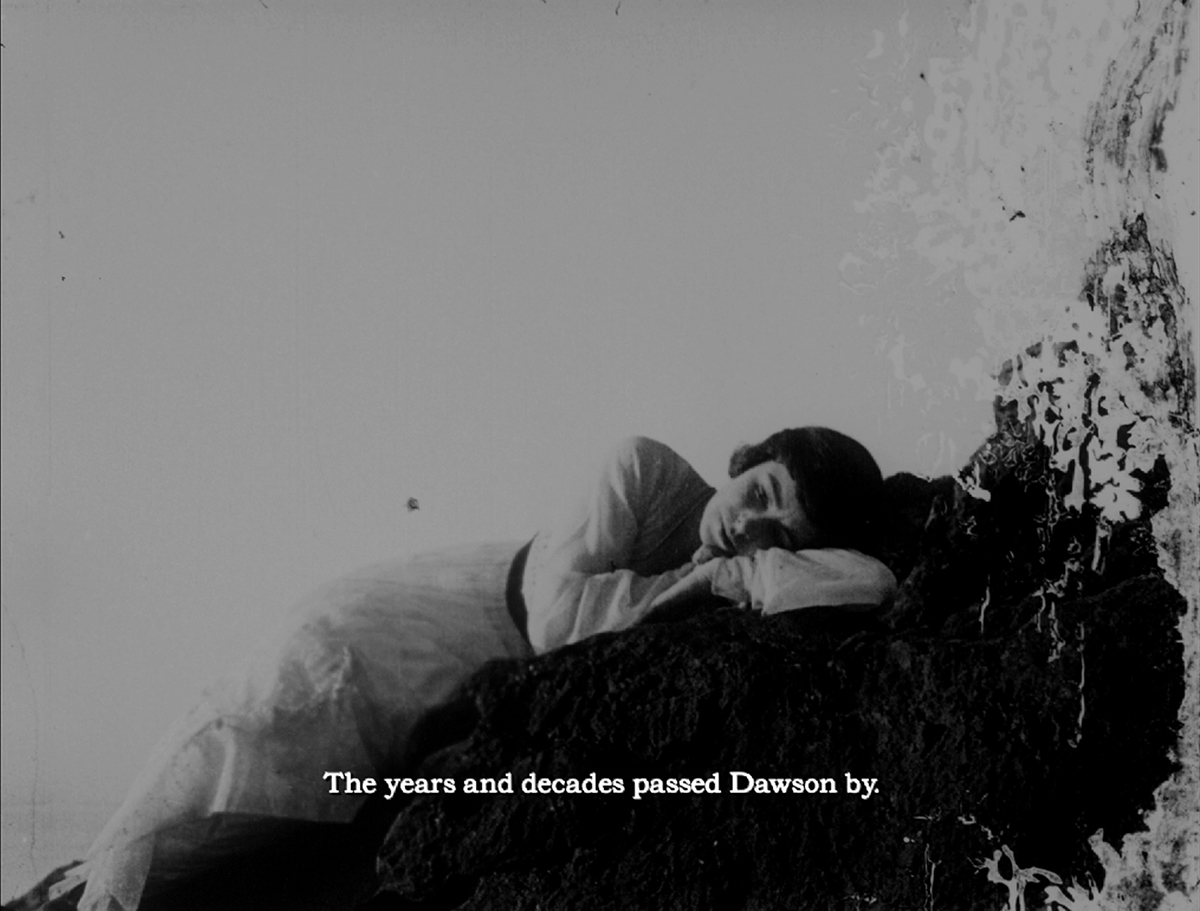

Top image credit: Dorothy Davenport in Barriers of Society (1916), Dawson City: Frozen Time, courtesy of Hypnotic Pictures and Picture Palace Pictures