RealTime dances: the big picture

RealTime’s coverage of Australian contemporary dance was unprecedented. Until their first edition in 1994, the major papers mainly covered established companies and artists presented in ‘legitimate’ theatres, and Dance Australia magazine rarely veered beyond major dance organisations in preview or review. There were very few other outlets for dance criticism so that, more often than one might expect, RealTime was the only place that independent work (the largest sector in the field) was reviewed. This was recently pointed out by Branch Nebula who have depended on RealTime’s support as their only review outlet since 2008 (Brannigan, Interview with Branch Nebula Part 1). Due to the commitment of editors Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter to this breadth and depth of coverage, RealTime has been pivotal in writing the story of Australian contemporary dance since the 1990s, mapping national trends by carefully holding ephemeral works in excellent writing that speaks to us across decades. The discourse has fed the form, filling in blank spaces in the mediascape and the archive, and giving voice to artists themselves.

Following the trend that emerged from the critics imbedded in the New York experimental art scene in the second half of the 20th century, local writers responded to the work of peers and colleagues in the supportive context of RealTime where the review form’s documentation function was taken seriously. As I’ve noted elsewhere, RealTime offers readers consistent coverage of an artist, tracking their ‘moves’ over a number of years (Brannigan, Introduction: RealTime Dance).

Key fellow-writers over many years have included Jodie McNeilly, Pauline Manley, Julie-Anne Long and Philipa Rothfield—all involved in our local scenes as dance artists, dramaturgs, curators and pedagogues—writing alongside journalists, academics and freelancers like John Bailey, Maggi Phillips, Ben Brooker, Jana Perkovic, Anne Thompson, Varia Karipoff, Linda Marie Walker, Carl Nilsson-Polias, Kathryn Kelly, Jonathan Bollen, Rachel Fensham, Douglas Leonard, Sharon Boughen, Sarah Miller, Andrew Fuhrmann and Jonathan Marshall, as well as Gallasch and Baxter. Artist-writers were a part of the mix, such as Eleanor Brickhill, Zsuzsanna Soboslay, Martin del Amo, Vicki Van Hout, Nikki Heywood, Tony Osborne, Bernadette Ashley and Jane McKernan. RealTime’s commitment to developing a field of criticality for dance through numerous workshops and masterclasses has also paid off with a new generation of dance writers emerging in the 2000s, including Jessica Sabatini, and Cleo Mees.

The local activities in each Australian state and territory have also met on the pages of RealTime, a rare thing given there is no national dance festival and despite strong links between individual artists across state lines. In 2010, Sophie Travers surveyed the issue of national touring, a huge deficit that has unfortunately only worsened in the last decade (Australian Dance: Unseen at Home, RT95 Feb-March 2010). While Dance Massive as been touted as an Australian dance festival, it remains Melbourne-centric and thus hasn’t solved the problem of repertoire mobility. Andrew Fuhrmann’s review of the 2017 festival included two Melbourne artists of the four he covered, however Melbourne artists actually made up three quarters of the Dance Massive program (Experience into Dance: Translation and Failure, RT38 April-May 2017).

Byron Perry, Stephanie Lake, Alisdair Macindoe, Conversation Piece, Lucy Guerin Inc, 2013, photo Ponch Hawkes

Victoria

Melbourne has a reputation as the spiritual home of dance in Australia, housing the Australian Ballet and its school and the Dance Department at the Victorian College of the Arts which established the first conservatoire model dance degree in Australia, producing some of our best dancers and choreographers, alongside the Deakin University dance program which established the first Australian Dance BA focusing on Education. There is no doubt that the city has the busiest dance scene and RealTime has documented the institution of Chunky Move (1995) (Chunky Move, Wet and Bonehead, RT24, April-May 1998) and Lucy Guerin Inc (2002). Jonathan Marshall surveys Guerin’s body of work on the cusp of this change (Between Temperature and Temperament, RT52 Dec 2002-Jan 2003) as a hub of opportunity and resources for the community. Lineages flowing out of this infrastructure are recorded in reviews of the second generation choreographers such as Stephanie Lake (Marshall links her style to Phillip Adams in Stephanie Lake, RT57 Oct-Nov 2003), Antony Hamilton (Jessica Sabatini, Breaking Through the Fog of Myth, RT122 Aug-Sept 2014), Byron Perry and Jo Lloyd, whose early work was supported by Guerin (Philipa Rothfield, Lateral Moves, RT70 Dec 2005-Jan 2006), Lee Serle (see Bernadette Ashley on his The Three Dancers for Dancenorth, From Picasso to Music to Dance, R134 Aug-Sept 2016) and Luke George (Virginia Baxter matches the energy of George’s Now Now Now in her response, Present Tense, RT102 April-May 2011). Strong links with visual arts venues and post-conceptual tendencies have distinguished the Melbourne field of work and shaped the emergence of the Keir Choreographic Award, Australia’s first choreographic prize.

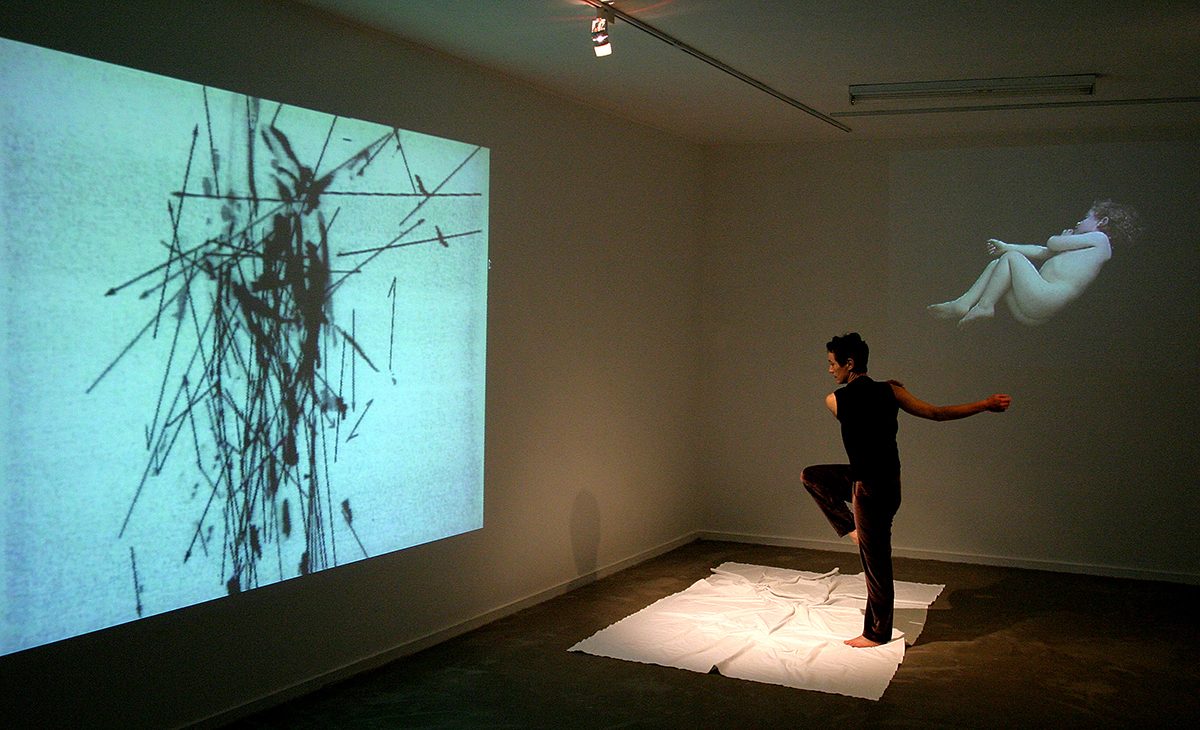

Victor Bramich, Lisa Griffiths, Shona Erskine, Nalina Wait, Fine Line Terrain, Sue Healey, 2004, photo Alejandro Rolandi

New South Wales

The Sydney dance scene encompasses Sydney Dance Company, Bangarra and the independents, the latter being strongly linked to Performance Space historically. Performance Space and RealTime were synonymous for me in the 1990s and early 2000s and One Extra (directors Graeme Watson, Julie-Anne Long), Dance Exchange (Russell Dumas) and Rosalind Crisp’s Omeo Studio completed the picture. As well as reviewing works made by Sue Healey, Rosalind Crisp, Shaun Parker and Martin del Amo, RealTime has since tracked the shift to a fragmented but exciting diversity of venues alongside the demise of access to the larger presenting venues in Sydney, not just for the small-scale works but our major dance companies also. (Gallasch comments on the ecological challenges in Sydney in Readymade Work’s Very Happy Hour, RT Online 1 May 2018).

After a series of Spring Dance programs (2009-2012), the Sydney Opera House closed its doors on Australian contemporary dance (except for Bangarra) until Fiona Winning’s arrival there in 2017 as Director, Programming. A modestly numbered, but highly proactive new generation of artists including Ivey Wawn, Angela Goh, Bhenji Ra, Rhiannon Newton and Amrita Hepi, have occupied galleries, clubs, and public spaces (Cleo Mees on Rhiannon’s work at Firstdraft, Dancing into Infinity, RT Online, 29 Aug 2017 and Laura McLean on Goh and Ra at the same gallery, Techno-Shapeshifting, RT Online 26 April 2017).

Beyond the inner city, Western Sydney’s FORM Dance Projects at Parramatta Riverside, Campbelltown Arts Centre and Newcastle’s Catapult Dance nurture and present important new work. See Pauline Manley’s comments on culturally sharp programming at FORM (Common Anomalies: Dancing with Difference, RT Online 21 November 2017), the editorial Growing Choreography in Newcastle (RT Online 16 Nov 2016), and my interview with then Campbelltown Arts Centre CEO Lisa Havilah and curator Emma Saunders (RT93 Oct-Nov 2009). Havilah’s collaboration with Saunders and Susan Gibb in 2009, What I Think About When I Think About Dancing, set the scene for this expansion of dance in Sydney and pioneered new curatorial directions across dance, performance and the gallery.

Western Australia

In Perth Sarah Miller’s tenure as Artistic Director at PICA (Perth Institute of Contemporary Art) imbedded contemporary dance in that institution’s programming. Dancers Are Space Eaters, launched in 1996, was perhaps Australia’s first contemporary dance festival (Rachel Fensham and Sarah Miller, For the Thinking Dancer, RT 11, Feb-March 1996; Grisha Dolgopolov, Who Said? RT34 Dec-Jan 1999). Miller was also a reviewer of dance for RealTime; her 2001 review (RT 37 June-July 2000) of a Paul O’Sullivan and Sue Peacock double-bill mentions other key figures of a generation: Stefan Karlsson, Olivia Millard, Sue Peacock, Sete Tele and Claudia Alessi (and I would add the important Chrissie Parrott). The Dance program at the West Australian Academy of Performing Arts supports local artists with teaching and is another source of new generations of dancers and makers.

Coverage of Perth artists by Jonathan Marshall, Maggi Phillips and Nerida Dickinson saw the emergence of a new generation including Paea Leach, Aimee Smith, Laura Boynes and Olivia Millard, and the MoveMe Festival (Marshall, MoveMe Festival 2016: The Call to Dance, RT Online, 24 August 2016). Strut Dance, established in 2003 by Sue Peacock and Gabrielle Sullivan, joined Dancehouse in Melbourne and since then, Critical Path in Sydney to create a network of like-minded organisations servicing artist development.

Queensland

The Queensland scene has been diverse geographically, culturally and generically, with Dancenorth, directed by Kyle Page, touring internationally and operating from Townsville, Bonemap in Cairns and Gavin Webber and Grayson Millwood with their company, The Farm, on the Gold Coast, bringing a European style of dance theatre to the state and beyond. Dance reviewers included the late Doug Leonard, Julia Postle, Shaaron Boughen, Bernadette Ashley (responding to Dance North over many years), Rebecca Youdell and Kathryn Kelly.

In Brisbane, from the 1990s on the Suzuki Method was influential via the companies Zen Zen Zo and Frank Theatre (John Nobbs, Jacqui Carroll), as have been circus and performance. Lisa O’Neill (ex-Frank) and Brian Lucas (including his work with Expressions Dance Company) have been key players, and mentors, alongside newcomers like choreographer Lisa Wilson, while QUT dance graduates feed the local dance scene. The influence of South Pacific cultures is felt in the work of Polytoxic (Efeso Fa’anana, Leah Shelton, Lisa Fa’alafi; see Unpacking South Pacific fantasies, RT72, April-May 2006) and Indigenous culture in the works and advocacy of Marilyn Miller and BlakDance, the Brisbane-based peak body for Indigenous dance in Australia. 2017’s Supercell Festival of Contemporary Dance revealed the potential of a much-needed international dance event.

Zoe Barry, Anastasia Retallack, Safe from Harm, choreographer Ingrid Voorendt with Restless Dance, 2008, photo David Wilson

South Australia

Writers Anne Thompson, Helen Omand, Linda Marie Walker, Jonathan Bollen and more recently Ben Brooker have covered dance in Adelaide where ADT (Australian Dance Theatre) has held its ground for decades. The company entered a new phase, extensively covered by RealTime, when Sydney-based choreographer Garry Stewart took on the directorship in 1999 and engaged with, among others, scientists and media artists. Leigh Warren and Dancers has also played a key role in Adelaide’s dance ecology, including collaborations such as Philip Glass’ opera Akhnaten with the State Opera of South Australia.

A local independent scene has produced notable female dancemakers such as Astrid Pill, Katrina Lazaroff, Fleur Elise Noble, Helen Omand and Alison Currie, Ingrid Voorendt, Gabrielle Nankivell and Larissa MacGowan (the latter two ex-ADT). Restless Dance Theatre, a rare disability arts company rooted in dance, was founded in 1991 by Sally Chance who was interviewed about its origins by Anne Thompson (Enabling Dance, RT22 Dec-Jan 1997). Subsequent artistic directors have included Voorendt and Michelle Ryan.

Adelaide is also the home of the OzAsia Festival which has recently come of age with a strong dance focus, connecting local artists such as Alison Currie with peers in the region (Brooker, OzAsia 2018 Performance: More Than Cultural Diplomacy, RT 5 Dec 2018).

Tasmania

Salamanca Moves 2016 in Hobart, covered by Lucy Hawthorne, showcased the local scene alongside international acts, putting local artists into dialogue with significant internationals such as Liz Aggis (Internationals, Locals, Any Body and Every Body, RT Online 19 Oct 2016). Tasdance, Second Echo Ensemble, and MADE (Mature Artist’s Dance Experience) and, at various times, independents like Wendy Morrow and Wendy McPhee, have all kept contemporary dance humming across generations, as reviewed by Sue Moss, Judith Abell and Diana Klaosen. Tasmania is also home to youth-focused companies Stompin and DRILL. Many emerging Australian choreographers have cut their teeth in our most southern state with Tasdance and Stompin in particular.

Northern Territory

RealTime has followed Northern Territory’s community-based dance company Tracks, which consolidated under the name in 1994, the same year as RealTime’s founding (Joanna Barrkman, Tracks: New Venue, New Artists, RT57 Oct-Nov 2003). Tracks has featured strongly in many Darwin Festivals including a collaboration with Darwin-based choreographer and Larrakia man Gary Lang (Malcolm Smith, The riches of rusting RT64 December-January 2004). Lang is artistic director of NT Dance Company; Fiona Carter reviews his work Mokuy (Healing the Pain of Loss, RT121, June-July 2014).

ACT

Coverage of dance in Canberra (from 1980 to 1996 once home successively to Human Veins Dance Theatre, Meryl Tankard Company and Vis-a-Vis Dance) was largely limited to reviews of QL2 Dance and its impressive youth group Quantum Leap (Zsuzsanna Soboslay, Sharing Country, RT117 Oct-Nov 2013.

Deanne Butterworth, Kylie Walters, Jo Lloyd, Shelley Lasica’s Action Situation, 1999, photo Kate Gollings

A visual arts dance paradigm, Keir Awards & Post-Dance

The Keir Choreographic Awards were established in 2014 though a partnership between philanthropist Philip Keir and the Australia Council for the Arts. Some of the teething problems were recorded in RealTime; Keith Gallasch documents the controversy over ‘form’ that the first iteration precipitated in an article that called for a public discussion that has never happened (Was There Dancing?, R123 Oct-Nov 2014). That the judging panels have included so many visual arts specialists indicates the current liaison between dance and the visual arts, a tendency that emerged from the intermedial hotbed of Brussels in the early 1990s in the pre-‘conceptual’ work of Meg Stuart. Since then, it has been connected to a trend towards ‘non-dance’ led by primarily male French choreographers and expressed fully in Boris Charmatz’ Musée de la danse. This has resulted in many and varied experiments across disciplinary borders, including local artists such as Lizzie Thomson, Matthew Day, Brooke Stamp and Angela Goh. Shelley Lasica has occupied this terrain since the early 1990s and RealTime has covered her body of work extensively, with special attention to her work from Philipa Rothfield (see for example, A Differential Tale, RT30 April-May 1999).

Contemporary Indigenous Dance

RealTime’s coverage of contemporary Indigenous dance has consistently identified exciting new artists in the field, and recognised the achievements of established ones. The editors’ support of artists such as Vicki Van Hout has done much to encourage and disseminate their work, as was recently recounted by the artist (Brannigan, Interview with Vicki Van Hout, Part 1) Keith Gallasch’s reviews of Van Hout’s work are exemplars of the role that the reviewer can take in bringing to light new artists and uncovering their innovations (Brilliance, Shimmer, and Shine, RT103 June-July 2011). Van Hout has gone on to write pieces for RealTime and her blog for FORM, providing an important Indigenous voice on dance, including her musings on an issue close to her heart: the tensions between Indigenous cultural protocols and innovative arts practices (Burning Issue—Authenticity: heritage and avant-garde, RT111 Oct-Nov 2012).

Torres Strait Islander Ghenoa Gela, winner of the 2nd Keir Choreographic Award in 2016, was reviewed by Andrew Fuhrmann who saw promise in the artist amongst stiff competition, and an investment by Keir in choreographers exploring non-Western cultural forms was continued with the excellent Javanese-Australian choreographer Melanie Lane taking the award in 2018. Broome-based Dalisa Pigram, co-artistic director of Marrugeku with Rachael Swain, has also been followed closely in RealTime (video interview by Gail Priest, We Can All Dream, RT125, Feb-March 2015). The magazine has also covered high profile artists such as Stephen Page and is Bangarra Dance Theatre artists Patrick Thaiday and Elma Kris. (RealTime mentored young Indigenous writer Rianna Tatana through her interview with Kris, Elma Kris: From a Torres Strait Islander Perspective, RT124 Dec 2014-Jan 2015.)

2000s and screen dance

I think my first article for RealTime was written in 1997 on the Microdance series of shorts made for ABC TV. RealTime already loomed large as my window onto the experimental arts in Sydney, Australia and the world. I transferred information in their advertisements into my diary diligently, and followed the careers of dance artists through the thick descriptions encouraged by a nebulous ‘house style’ that privileged careful accounts over reductive judgments. In RealTime I also found somewhere open to publishing articles emerging from my burgeoning interest in intermedial practices across dance and film/video. The magazine maintained a commitment to covering this niche field of practice, commissioning myself and writers overseas to cover the international field, supporting events closer to home through smart critique, and running a workshop for aspiring writers alongside the 2008 edition of ReelDance International Dance Screen Festival in Sydney (RT85 June-July 2008).

Interest from Australian funding bodies in the dance-screen nexus waned after the first decade of the 21st century, and the international scene slowed down as artists across the world seemed to shift away from this expensive mode of choreographic production that requires serious resources. The most recent coverage was of Samaya Wives’ (Pippa Samaya and Tara Jade Samaya) The Knowledge Between Us (2017), which won the Australian Dance Award for the awkwardly named Dance on Film or New Media prize (Gallasch, Samaya Wives: One-Minute Dance Award Winner, RT Online, 26 Sept 2017). Young artists do seem to be returning to the form, and there has been renewed talk of screenings at ADT in Adelaide and Lucy Guerin Inc in Melbourne.

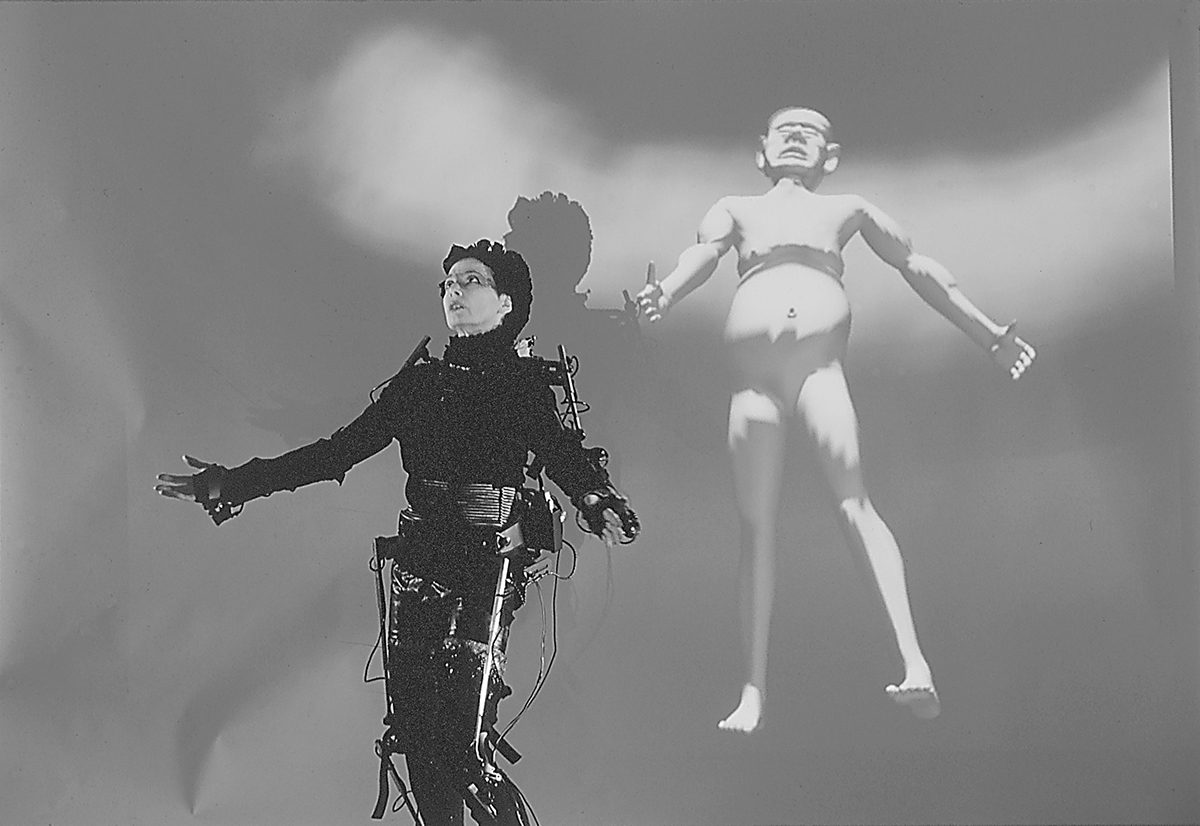

Dance and new media technologies

The investment of funding bodies in the dance-technology interface resulted in a flurry of activity across the end of the 1990s and beginning of the 2000s. Leaders in this field have been Company in Space (Hellen Sky and John McCormick) and Margie Medlin. Medlin joined temporary Australian resident Gina Czarnecki in scoring the prestigious Sciart award from the UK’s Wellcome Trust for her work Quartet (Brannigan, Music Makes Moves, RT 76 Dec 2006-Jan 2007).

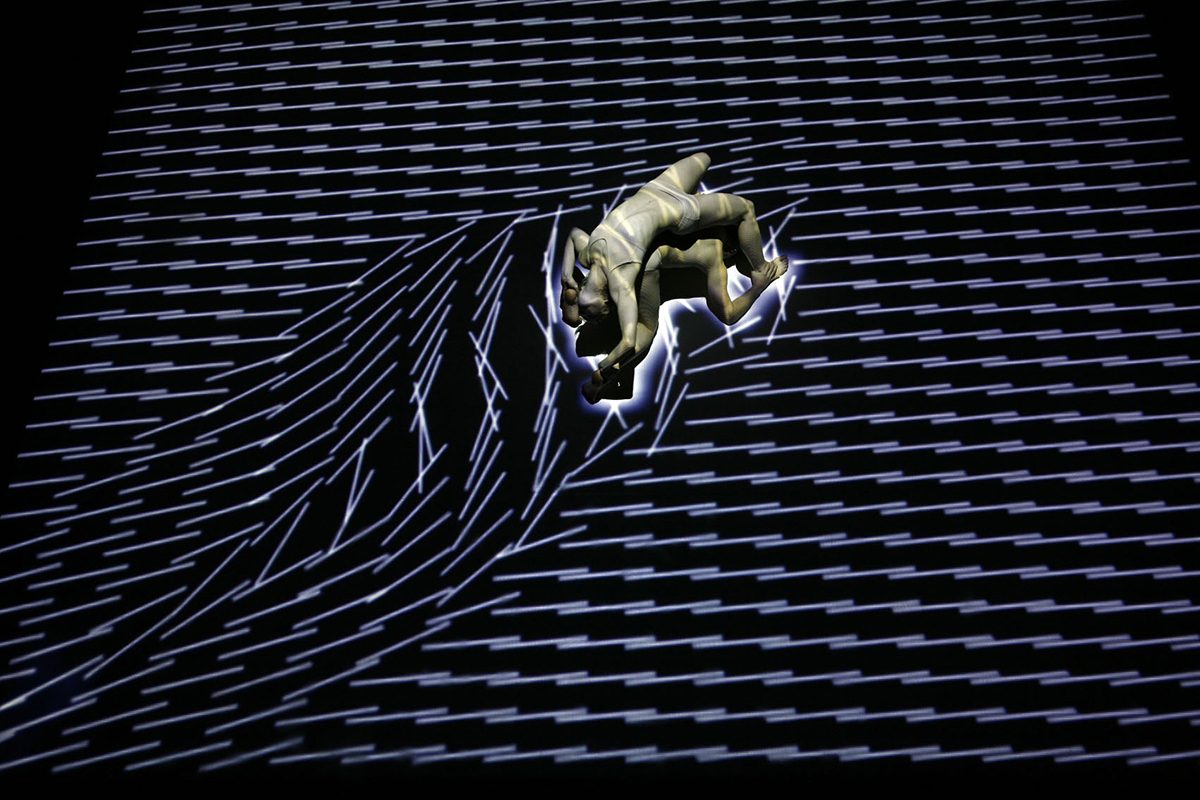

RealTime traced the development of the sub-field, and one of the most positive reviews was Gallasch’s snappy response to Gideon Obarzanek’s simple and moving Glow (Doubly Emergent: Chunky Move’s Glow at The Studio, RT78 April-May 2007). He writes: “The emergent art tool is at one with the dancer’s body in an account of an emergent organism, a huddled inhuman shape inching across the screen-floor.” In her role as Director of Critical Path, Margie Medlin championed this work. Her SEAM conference of 2010, sub-titled Agency and Action (the series running 2009-2014), was a singular event combining a new media performance program with a rigorous conference (Rackham, Mind, Play, Empathy and Machines, RT100 Dec 2010-Jan 2011).

Other publications

The booklet In Repertoire: A Guide to Australian Contemporary Dance (RealTime for the Australia Council, 1999, revised 2003) and the book Bodies of Thought: 12 Australian Choreographers (Ed. Erin Brannigan and Virginia Baxter, Wakefield Press-RealTime, 2014) are publications that draw on the magazine’s dance content as consolidated in RealTime Dance, an online resource established in 2014. In Repertoire is an Australia Council-commissioned snapshot of Australian choreographic works ready to tour in 2003. In RealTime Dance, Dance File lists Australian artists and companies alphabetically, with links to relevant RealTime articles as well as a considerable catalogue of international artists and companies.

Bodies of Thought is the first publication to bring works of key Australian choreographers together to map common approaches and themes nationally, combining interviews with critical essays supported by the RealTime archive. In this case, RealTime reviews are supplemented online with external reviews, putting RealTime into critical dialogue with other reviewing outlets. Added to this is RealTime TV which features interviews with Lee Serle, Anouk van Dijk, Dalisa Pigram, Tim Darbyshire and many others, and Dance on Screen which brings together writing on this genre.

Conclusion

Even with a most optimistic view onto the new era of democratised, online arts reviewing, it is hard to imagine another publication that could put contemporary dance into dialogue with the other arts in the same way RealTime has done. RealTime seemed to understand the leading role dance has taken, quietly and persistently, on numerous fronts; in innovating the review format, engaging with other media in an inclusive choreography with whatever materials were necessary, and the modelling of community practices so integral to the art form. The strength of the magazine in following the art form in its interdisciplinary adventures is dependent upon an editorial scope that takes it all in. For this reason RealTime’s editors Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter, and their vision for a publication where dance took centre stage, will be sorely missed by Australian dance artists and aficionados alike.

–

Erin Brannigan has written for RealTime since 1997, was the founding Director of ReelDance (1999-2008), has curated dance screen programs and exhibitions for international festivals, programmed and commissioned works for installation exhibitions and led Choreography and the Gallery: A One-Day Salon (Biennale of Sydney 2016, Art Gallery of NSW and UNSW). Erin is a Senior Lecturer in Theatre and Performance Studies at UNSW.

Top image credit: Be Your Self, Australian Dance Theatre, photo Chris Herzfeld, Camlight Productions