OzAsia: The End: Almost human

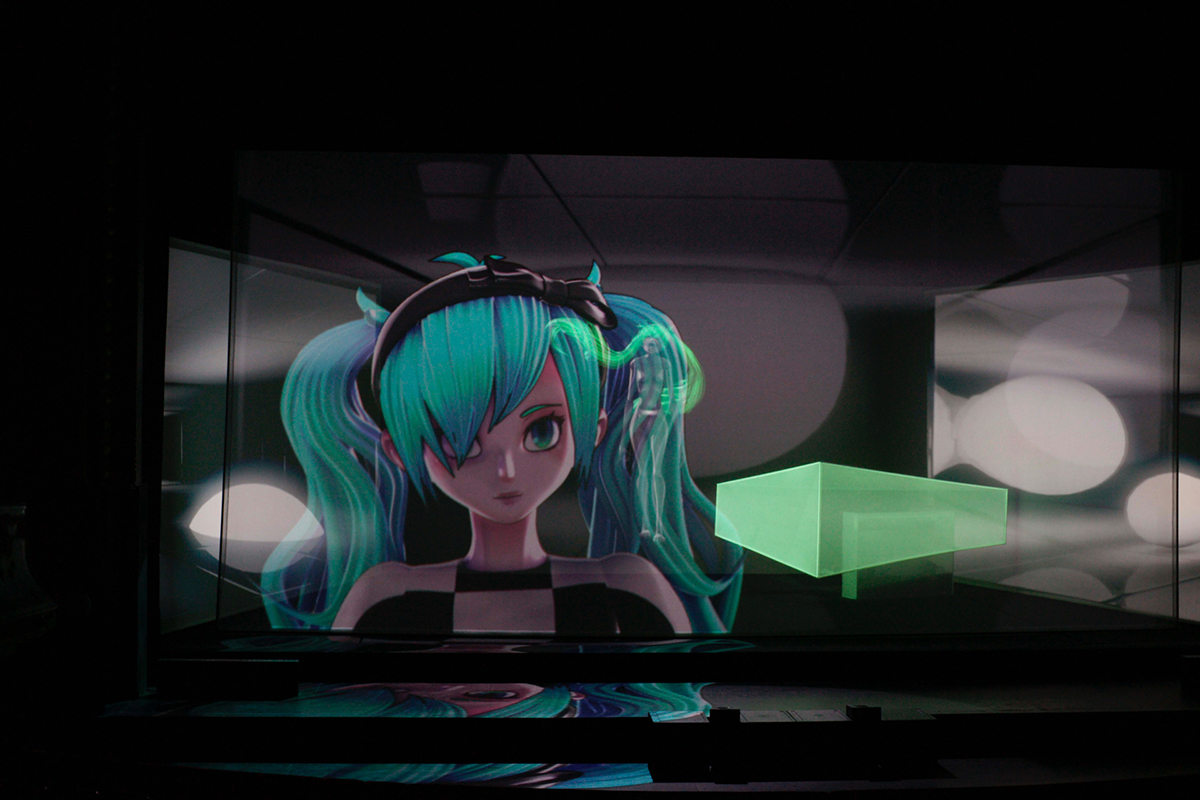

The End is a highly unusual meditation on mortality in which a virtual pop star suffers intimations of her coming death. The eternally 16-year-old, 3D-animated vocaloid singer Hatsune Miku (literally “the first sound from the future”) has a huge following in Japan and Southeast Asia, appearing on large screens in concerts and singing to live musical accompaniment. In The End, composer Keiichiro Shibuya, himself famous, and his team emphatically duplicate the concert feel with a big screen and powerful wraparound sound, but lift Miku out of the pop realm into an existentially fraught cosmos. She looks similar to her pop self — skinny, wide-eyed, ribboned turquoise hair flying wide — but the calculated cuteness and sexy teen moves have gone. So have the sexy outfits, replaced with a Louis Vuitton-designed range patterned with large and larger checks in a limited set of colours. Gone too are Miku’s multitudinous songs about love, replaced with recitatives and arias of contemplation and internal conflict. Also missing is the stable animated world that sustains her in manga and anime worlds. Instead, in fragile spaces that blur and fade, she is subject to ominously recurrent transmission glitches. And unlike her in-concert self, she rarely moves with simulated human agility; save when running though outer space, she is frequently still, seen in radically shifting perspectives, often face to face with us, or floating.

Shibuya and team have thus created a Miku who is transparently a virtual human, akin to Skeleton, the android who performed in response to the music of the composer and the Australian Art Orchestra in OzAsia’s Meeting Points: Scary Beauty. And akin too to the replicants in Blade Runner and so many other sci-fi creations, artificial beings for whom sudden awareness of mortality, in the face of their apparent perfection, is overwhelming — hence the play on “perfect”/’imperfect” in The End’s libretto.

The End, image Kenshu Shintsubo

Miku’s self is as unstable as the world around her — other figures appear, evoking other dimensions to her psyche. The End is not a monodramatic opera. Miku’s companion is a cute, tubby cartoon cat fixated on being her guardian, desperately hanging onto their bond as the singer slips from it: another instance of Miku’s removal from her teen world. More demanding is the arrival of a stranger emerging from the deep distance, at first glance another Miku but naked and with a skull face. The cat nervously exits and an exchange ensues between our heroine and her doppelganger to the opera’s end, face to face and then, curiously, by phone. At first Miku thinks the woman an imitator — “Are you on a diet, like me” — but reality gradually takes hold — a dry, musty, powdery odour, which prompts the donning of a gas mask. Miku’s other says, “When in the end they die [humans] smell the most.”

However, rather than being repelled, Miku needs to connect with her effectively dead self to learn about dying, until she is ready to let go of her living self. The two engage in lyrical half-sung dialogues, voice pitches barely distinguished, heightening the sense of interior crisis.

The opera’s stage design lends weight to Miku’s plight. As well as a large forescreen, there are three more angled behind it providing gripping depth-of-field with projected images on each amplifying the play of intense intimacy and profound distance. It’s most powerful when, in a burst of emotional strength Miku becomes a universe-traversing dragon, her face staring out from between the beast’s open jaws as Shibuya’s score thunders with bracing prog rock grandiosity. Elsewhere the screens reveal depthless spaces in which undetailed Miku models or dummy body parts slowly tumble, painfully underlining her artificiality. In a fantasy of an imagined bodily self, we are plunged into Miku, coursing down the oesophagus and up to the heart, a jewel-like sculpture which, stuck with forks, transforms into the singer’s face as she asks herself “Why are you so scared?” and recalls a cut finger which she worries is a false memory.

The End, image Kenshu Shintsubo

The genius of the stage and projection design lies in its creation of an entirely abstract space — a white box, a perpetually transformable tabula rasa for the projections of the artists, Miku and ourselves. Within it floats another box, itself a screen, and within it in turn, the composer-performer, barely visible, the consciousness from which The End emanates.

As Miku’s end looms, running through space as if suddenly free to face death, she yearns nonetheless for connection: “I’d like you to watch me and I will watch you too,” and some kind of eternity: “A melody to sing over and over.”

The cat returns, huge, looming over Miku in a final effort to hold onto her (“You’re much too cute for a human being” and, contrarily, “Remember when we were one? You were much closer to a human being”), but, glitching, floats helplessly away like a balloon. To complete her individuation, Miku then breaks off a phone conversation with her doppelganger but not before the pair entwine, drifting in space, the skull face of her other becoming her own before dissolving into nothingness, the richly layered music speeding with the emotion of union and separation.

Miku appears to be about to take flight but disappears into total whiteness from which dark shards surge as Shibuya’s score with organ churns relentlessly. Miku reappears, floating on her back: head, arms, legs hanging limply — “Do I look like I’m dead or only asleep. It makes no difference for you.” In a series of single utterances she sings movingly of her self rapidly departing — she cannot see, turn, touch, grasp…

In the opera’s last phase the meaning of “you” becomes richly ambiguous – the ‘you’ that is her doppelganger, which is herself; the ‘you’ that is us, her audience; and some other ‘you’ — “You’ll be in my memory forever,” “I’ll scream your name but not be able to call you,” “I’ll no longer have to keep you behind my eyelids.” It’s known that the opera was composed in the wake of the suicide of Shibuya’s fashion designer wife, Maria, adding another layer of emotional response to The End’s sad tale of a puppet given provisional life. Doubtless for Shibuya, as for Miku,”Dying was disappearing for other people. But not for me. Dying was the furthest thing from my mind.”

The script was written with Shibuya by playwright and novelist Toshiki Okada, Artistic Director of the theatre company chelftisch (God Bless Baseball, OzAsia 2016; Time’s Journey Through a Room, Asia TOPA, 2017), an ideal librettist given his incisively spare and quite lateral approach to dialogue, which here conveys the naivety of not merely a 16-year-old, but a virtual one. The limits of Miku’s reality are occasionally underlined with the cat’s report of rubbish piling up in the streets or by the sound of a helicopter thundering over us, but otherwise the singer’s world is a small one if metaphysically big.

The End might work for Miku’s pop fans (the few I saw appeared fully engaged) given the creative boldness of much manga and anime. The composer also works within careful limits, with hook-like recititatives that almost bloom into song and with songs that resonate closely with each other, as if to leave us with one haunting melody, richly and variously textured with beats, electronics, piano, organ, strings and enveloping spatial flow. Miku’s voice (built from an actual one) sits on the borderline of real and synthetic, but inclines deliberately to the latter — complexly tuned and textured by Shibuya and his vocaloid programmer — than to her often quite realistic pop singing. This again gives strength to Shibuya and Okada’s vision of an innocent technical intelligence burdened with the weight of mortality in a work that simultaneously resonates with our own experiences of facing death, our own or of others, at whatever age. Miku invites and warrants empathy in Keiichiro Shibuya’s splendidly realised virtual opera, growing more human the closer to death she comes.

The End can be found on YouTube with English subtitles.

For more about Hatsune Miku go here.

–

OzAsia: The End, performer Hatsune Miku, performer, director, concept, music Keiichiro Shibuya, original book concept Toshiki Okada, Miku costumes Mark Jacobs (Louis Vuitton), visuals YKBX, stage design Shohei Shigematsu, spatial sound design evala, vocaloid programming PinocchioP, lighting Akiko Tomita; Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide, 30 Sept-4 Oct

Top image credit: The End, image Kenshu Shintsubo