Cutting the new media umbilicus

Melbourne Film Festival’s Mousetrap prompts Darren Tofts to revise the language of the new media arts

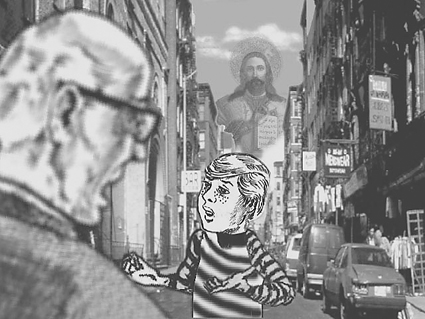

Rodney Ascher, Somebody Goofed, 2D computer animation and print ephemera

Why do we still talk of “new media”? Are we in the grip of a persistent cultural logic of digital neoteny? In a refreshing riposte to this desire to keep new media forever young, Mousetrap curators Martine Corompt and Ian Haig inform us that “in 1998 digital media is no longer a big deal.” While not overtly polemical, Mousetrap was as much an exhibition about digital screen culture, to be remembered for cutting the new media umbilicus. Any new medium is quickly absorbed into a culture (this is straight McLuhan 101), tarnishes with ubiquity, and ossifies into style. The laws of media are unforgiving. At a recent forum on visual design at Swinburne University, Christopher Waller (21C, Diagram) noted how the style of glossy, hyperreal power-imaging we associate with the 90s has already dated, and that nostalgia will eventually mentor its revival. Mousetrap demonstrated that la mode retro is a creative force to be reckoned with in contemporary screen culture, though not for anything of so recent a vintage. The diverse range of local and international work garnered for this exhibition declared a “longing for potentially obsolete analogue materials, such as over-exposed film-stock, yellowed paper and photographic grain.” Forget the future, digitally-created art looks like it has re-emerged from the past, “secondhand, tactile, decayed and disordered.” Pace Bruce Sterling, there’s no such thing as a dead medium. The experimental arts will always find a use for such things.

That out of the way we have another problem. Despite the diacritical impetus behind the exhibition, Mousetrap could not avoid falling foul of the regulation pigeon-holing as “multimedia” any artistic practice that in some way uses computers. The film festival organisers may have been trying to capitalise on the popular belief that the term multimedia is sexy. Or perhaps they simply didn’t know what else to call it. Either way, the work is partitioned off as being in some way different, and not necessarily integral to the screen scene created by the festival. To be fair, though, it is more important for this work to be included in such festivals than not. But the continued use of a term that has outlived its usefulness worries me. Multimedia was invented with a technical meaning in mind, referring to the incorporation of multiple signifying modes within the same apparatus. Inflections to do with new modes of creativity or sensibility made possible by this apparatus have never been part of its meaning. These days anything on a CD-ROM or the World Wide Web, or produced using Director, is automatically labelled as multimedia, often with little attention to what is actually going on from a representational or formal point of view. There is no question that discrete forms of screen-based arts, such as video, cinema and digital animation, will continue to thrive, and sustain their own forms of critical discourse. But at a time of energetic experimentation in the screen arts, as we are experiencing now, the continued use of narrow and historically specific terms such as multimedia is like the proverbial can tied to a dog’s tail.

It’s time we stopped using multimedia as a generic term to describe the very specialised and often idiosyncratic work being done by artists who happen to use computers. I propose the use of an alternative term which already has currency in the digital world (we’ll have to do something about that “digital” soon). The word is intermedia. Intermedia, with its suggestions of hybridity (a fusion or cross-fertilisation of different media forms) and intransitivity (between commencement and closure), recommends itself as a more apposite descriptor for the cultural production of the experimental screen arts.

The urge to graft and appropriate diverse media into a synthetic, intermedia environment has been around for some time (why multi rather than mixed media in the first place?). Digital techniques, while offering decisive enhancements, are best understood as enabling technologies that facilitate the importation of different signifying textures into a screen space, and the ability to recombine them in surprising, even unprecedented ways. As Ian Haig noted of the Mousetrap screening program, many of the works “employ digital tools to fuse together cell animation, live action, comics, stop motion animation and found imagery, often producing new hybrid forms of animation, which would not have been possible previously.”

The interactive exhibition offered a range of work that displayed the changing architectures of interface design and principles of interactivity. Presided over by one of the acknowledged masterpieces of intermedia, The Residents’ Bad Day on the Midway, it suggested a sharpened understanding of intermedia as being concerned with spatial relationships and immersive environments, rather than game-playing or puzzle-solving. This poetic was persuasively supported by Jim Ludtke, who emphasised in his artist’s talk the continued importance of exploration and narrative in intermedia (“the story’s the thing”). But the screening program was really the nodal point for Mousetrap’s intimations of intermedia. In bringing together national and international work that determinedly explores the poetics of hybridity, Corompt and Haig have charted more than trends and developments. Their astute sense of what is happening with the screen arts scene suggests that if there is such a thing as a digital body politic, it is being mutated from within by the recombinant force of bricolage. This process can be seen in the collagic, appropriationist style of Rodney Ascher’s punkish grapple with ultra-fundamentalism, Somebody Goofed (1997), which cleverly fuses 2D computer animation and print ephemera (comics, kids’ books, album covers) into a highly distinctive, estranging allegory of betrayal. It is also evident in Laurence Arcadias’ Donar Party (1993), a colourised steel-point etching twitched to grotesque life, which exploits the suggestiveness of a VRML walkthrough to document the pitfalls of a pre-electric surgical scene from the 19th century. As well, Adam Gravois’ atmospheric and decidedly low-fi Golden Shoes (1996) captured the dual intermedia aesthetic of recombination (it looks like a film, but it isn’t) and bricolage, the fine art of making do with whatever is at hand (such as low cost computers and software).

Mousetrap demonstrates that intermedia practice is more concerned with a type of sensibility or attitude preoccupied with all available media, than with the potential of digital technologies per se. Indeed, as Haig advances, the “works shown in Mousetrap expose the possibilities of what can happen when you fuse computer hardware and software, together with…an attitude which embraces the culture of underground comics, contemporary anime, and weirdo cartoons.” New media is dead, long live the re-animators.

Mousetrap, curated by Martine Corompt and Ian Haig, Melbourne International Film Festival; screenings State Film Theatre, interactives Melbourne Town Hall, July 23 – August 9

RealTime issue #27 Oct-Nov 1998 pg. 22