Okay, how is cyberspace like Heaven

Darren Tofts enters Margaret Wertheims’ pearly gates

Cyberspace is the ostensible topic of this book. It is really a kind of Cook’s tour of space as it has been conceived and visualised through the ages, from the soul-space of Christian theology to the hyperspace of multi-dimensional physics. It is important to keep any discussion of cyberspace within a historical framework and Wertheim has done an admirable job in providing an extended cultural history into which cyberspace can be situated. Her argument is a fairly simple one and, as the title of her book suggests, it measures cyberspace against a quasi-Christian view of space as being transcendent, immaterial and other. “Cyberspace is not a religious construct per se”, Wertheim suggests, but “one way of understanding this new digital domain is as an attempt to realise a technological substitute for the Christian space of Heaven.” There is nothing particularly innovative about this suggestion, as cyberspace has been theorised elsewhere as a “spiritualist space” (Michael Benedikt’s “Heavenly City”, William Gibson’s Vodou pantheon in Count Zero). What perhaps is new is the sociological spin Wertheim puts on the emergence of cyberspace at the end of the 20th century: “Around the world, from Iran to Japan, religious fervour is on the rise.” But Heaven is something to be put off for later, so I will return to this issue directly.

Cyberspace is the ostensible topic of this book. It is really a kind of Cook’s tour of space as it has been conceived and visualised through the ages, from the soul-space of Christian theology to the hyperspace of multi-dimensional physics. It is important to keep any discussion of cyberspace within a historical framework and Wertheim has done an admirable job in providing an extended cultural history into which cyberspace can be situated. Her argument is a fairly simple one and, as the title of her book suggests, it measures cyberspace against a quasi-Christian view of space as being transcendent, immaterial and other. “Cyberspace is not a religious construct per se”, Wertheim suggests, but “one way of understanding this new digital domain is as an attempt to realise a technological substitute for the Christian space of Heaven.” There is nothing particularly innovative about this suggestion, as cyberspace has been theorised elsewhere as a “spiritualist space” (Michael Benedikt’s “Heavenly City”, William Gibson’s Vodou pantheon in Count Zero). What perhaps is new is the sociological spin Wertheim puts on the emergence of cyberspace at the end of the 20th century: “Around the world, from Iran to Japan, religious fervour is on the rise.” But Heaven is something to be put off for later, so I will return to this issue directly.

How has the West configured space? This is the question that shapes Wertheim’s discussion and the book is structured around a series of discrete moments in the history of space. It is a very linear, tidy history, beginning with the theocratic world-view, as articulated by Dante and Giotto, which, via the Copernican revolution, Newtonian mechanics and Einsteinian relativity, incorporates the outer reaches of contemporary cosmology. As earthbound physicists such as Stephen Hawking contemplate the infra-thin spaces of quarks and virtual particles, they once again turn our attention to the sphere of abstraction that exists beyond the physical world-view that has dominated consciousness since the Enlightenment. Wertheim’s contention is that with cyberspace we have returned to a realm not dissimilar to the Medieval conception of “Soul Space.” Consistent with the transcendent motivation of this space of spirit, Wertheim refers to “cyber-immortality and cyber-resurrection.” Enter the “cyber-soul.”

There is a certain kind of logic in Wertheim’s account of a re-emergence of a conception of space that dominated an earlier age. However I have a number of problems with her anachronistic misuse of cybercultural terminology. For instance, Dante does not represent himself in The Divine Comedy as a persona but as a “virtual Dante”; the Arena Chapel in Padua is a “hyper-linked virtual reality, complete with an interweaving cast of characters, multiple story lines, and branching options” (the italics, which are telling, are not mine); Medieval thinker and theologian Roger Bacon was “the first champion of virtual reality.” To be fair, such throwaway lines detract from what are otherwise interesting discussions of the ways in which the techniques of representation yielded to the pressures of verisimilitude and the desire to create in the Medieval viewer/worshipper a more vicarious sense of presence, of actually being in the scene or space being described. This is in itself a fascinating issue, for as writers such as Stephen Holtzman and Brenda Laurel have suggested, VR concepts such as immersion have a respectable ancestry and their logic has hardly changed. This doesn’t give us licence, though, to return to the Middle Ages armed with cyber labels for our predecessors and certainly not with such abandon (The Divine Comedy “is a genuine medieval MUD”). Giotto was without question a pioneer in the “technology of visual representation.” He was not, though, our first hypertext author. We can perhaps claim that there was something hypertextual in the way the narrative is presented in the Arena Chapel, but we have to evaluate this against the rigid, hierarchical manner in which the Medieval mind read the world. Wertheim is sensitive to this, but fails to account for it adequately. She also fails to note that just because we have hypertext it doesn’t follow that it represents an episteme or way of seeing that residents of the late 20th century all share. Most visitors to the Arena Chapel today would more than likely read its narrative as a causal sequence of events. More to the point, they would presume that there was one.

The other major problem I have with Wertheim’s argument is the contention that cyberspace is “ex nihilo”, a “new space that simply did not exist before.” Contrary to Wertheim’s surfeit of space, I simply don’t have the space to take issue with this position. However as a statement it points to a worrying element of contradiction in her argumentation. In the same chapter we are informed that with cyberspace “there is an important historical parallel with the spatial dualism of the Middle Ages” (we are also informed that television culture is a parallel space or consensual hallucination and that Springfield, the hometown of the Simpsons, is a “virtual world”). In a book that attempts to synthesise such parallels and account for cyberspace as a return to a Medieval type of space, it is odd to read in the penultimate statement of the book that “Like Copernicus, we are privileged to witness the dawning of a new kind of space.”

The book is very distracting in this respect and it testifies to an unresolved tension within Wertheim’s assessment of cyberspace. While she is sensible and articulate in her delineation of space as it has been figured throughout history, she is still caught up with the novelty not of cyberspace, but of cyberspeak. There is not enough analysis of what type of abstraction cyberspace involves and how we actually relate to it spiritually or any other way. Too many of the familiar themes of cybercultural discourse are simply recapitulated, such as the possibilities for identity and gender shifting in MUDs, the liberatory potential for “cybernautic man and woman”, of avatars and interactive space and the hackneyed whimsy of downloading the mind into dataspace—et in arcadia ego. Any force that is generated by Wertheim’s main theme is lost as a result of the book’s straying off into the already said. How is data-space like the Christian concept of Heaven? This is an interesting question, but beyond the tropes of cyber-dualism and cyber-transcendentalism; nothing original in the way of a convincing answer is forthcoming.

The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace is consistent with much cyber-utopian criticism in its evaluation of cyberspace as a positive, therapeutic phenomenon: “There is a sense in which I believe it could contribute to our understanding of how to build better communities.” Well, I suppose we are still waiting to see if this will be the case or not.

In the meantime, how do we account for the fact of this new space? In response to this question, Wertheim advances her least convincing argument. Unsupported by any research and reliant entirely on speculation, Wertheim suggests that at a time of global religious enthusiasm “the timing for something like cyberspace could hardly be better. It was perhaps inevitable that the appearance of a new immaterial space would precipitate a flood of techno-spiritual dreaming.” As sociology The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace just doesn’t cut it. Despite the reservations I have with the book, it is nonetheless a useful study of the contemporary fascination with space and the historical legacy of Christianity, the history of ideas and the visual arts.

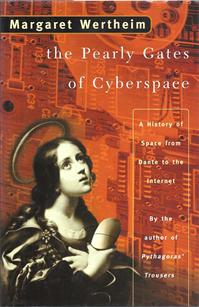

Margaret Wertheim, The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace, A History of Space from Dante to the Internet, Doubleday, 1999, ISBN 0 86824 744 8, 336 pp.

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 20