New media hum

Mike Leggett enters the hive of international digital media/web artists ≈and Jane Prophet

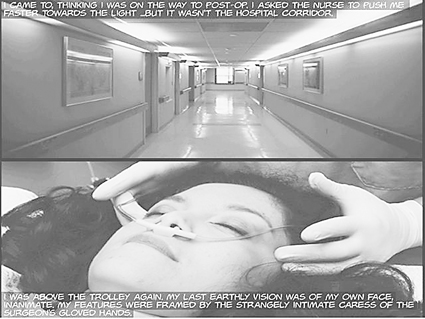

Jane Prophet, The Internal Organs of a Cyborg

Whereabouts at a film festival would you find “a chatterbox road-movie without the car and without the conversation”? Well, clearly not anywhere near the hype of Hollywood nor the profundity of a weekend conference, but actually in Wax, located in the bowels of the Melbourne Town Hall.

David Blair’s theatrically-distributed electronic 90-minute feature WAX or the discovery of television among the bees (1991) was seen previously in Australia during the Third International Symposium of Electronic Art (TISEA) in 1992. Waxweb, a “hypermedia” version of that work, then passed through various pupations including a version seen on the Burning the Interface International Artists’ CD-ROM during 1996/7.

Now in its final form, the principle of the piece is straightforward enough—“the first time user can watch the movie play from beginning to end. Then or later, any of WAX’s 1600 shots can be clicked, leading the viewer into a 25-section matrix unique to each shot. There, similar pictures, descriptive text, and moving 3D images interweave, coherently leading the viewer from one media to the next, within and between shot matrices, always moving in and out of the time of the movie…the perceived boundaries between the movie and the surrounding composition will dissolve, sending the movie into extended and apparently endless time, as if it were a temporary, grotesque world.”

Now that the work is described as a “micro-fiche lithograph on CD-ROM”, Blair sees other authors of the fantastic (Borges, Rimbaud) as his precursors who worked with words and to which, with words, he adds the “gathered material” of photograph, movie and sound; and employs hyperlinking software to enable through “micro-compositions” the free association of “storyettes” and the fabrication of a “story or writing machine.” A brief engagement with collaborative writing approaches, through the Waxweb website in the mid-90s, was abandoned in favour of the principles of the auteur.

“The viewer need only watch the movie, or click a few times. To completely support this activity, the author has created more than 1 million picture, hypertext, and 3D links; the animated 3D scenes would play 40 hours if placed end to end. But this is not a database…It is a movie composition, made for many sorts of viewer pleasure.”

Waxweb resists any sense of immersion in the labyrinth that might be expected of a neo-symbolist work. It is “a composition” with a foundation of words and word play that, combined with the “faux documentary” of the Wax movie, barely suppresses the absurd and the ironic. The frames launched by the browser become like postage stamps lined up within the pages of an album, providing pathway options a plenty, and eye-watering dismantlement of the girders, struts, plates and rivets of Blair’s composition, each one indexing a virtual point in film time.

Blair identifies the bensai, or narrator-lecturer present at the screenings of silent films in Japan until the 1930s, as the proto-interactive interface designer. Over the last few years, The Telepathic Motion Picture of The Lost Tribes and Jews in Space have been in initial development (mostly in Japan during a 2 year stay), and having secured completion funding, will become more resolutely a “unified cross-media project” encompassing DVD and website elements.

David Blair, an American in Paris, was a guest of The Bug, a title given to a series of events hosted by Cinemedia and the Melbourne International Film Festival during July and August, a chrysalis within the buzzing halls of Swanston Street, attached precariously to a basement room used as the Nokia Festival Club.

Kevin Murray selected 13 interactive CD-ROM works for the now fashionable exhibition element of the film festival, the budget also funding another overseas artist, London’s Jane Prophet, to talk about her work, both guests later giving similar presentations at Artspace, Sydney.

Their work was linked, so to speak, by the honey bees’ hexagonal cell. Swarm, an installation and interactive website by Prophet, offered visitors an immersive entry into crowd consciousness. Using the metaphor of the hive to collect and relate stories, and the simulation of bees on a large projection screen that responded to the presence of visitors by mapping movement around a mat in front of the screen, the experience of telekinesis and noisy play between visitors using the installation contrasted with the quiet area behind the screen in which the collected stories were related.

Technosphere also explored artificial life (AL) paradigms through one of the earliest examples of website interactivity that enabled participants to design their very own ‘critter’, its appearance, its eating habits and demeanour, and then to receive on a regular basis email messages that kept the ‘parent’ informed about the progress of its progeny through a pretty grim daily round relieved only, it seems, by reproductive encounters, eating, combat and finally death.

Jane Prophet graduated in the mid-80s in performance-based art before completing a theory-based doctorate: “I’ve always thought of myself as a visual artist but at this email stage of Technosphere the experience on the net was not a very satisfying visual experience. However, in terms of receiving feedback about my work it has been phenomenal.”

Custom-coded software was developed by Prophet’s collaborators Dr Gordon Selley and Dr Richard Hawkes as there was no money to buy anything off the shelf—”proprietary software at least avoids the headaches of commercial upgrades.” It handles the multifarious commands generated by the site and results in the despatch of 20-30,000 email messages a day.

“In 1995 when we were applying for funding, there was really nothing like it, as art or as AL on the web, and we didn’t know if it would be interesting. In fact it was terrifyingly interesting to people, which is why it is still going, even though it’s ancient in terms of the net world. A month ago we had our millionth creature made now that we’re up to 70-80,000 hits a day—we shift about 2 gigabytes of data a day and replace a hard drive every 6 months—it’s a really busy site still…”

“Probably the most interesting thing about the project is its anthropological/sociological elements and how that has made all of us working on Technosphere think more about work on the net. For instance, whenever the site is closed for short periods regular users get very upset. Or if the site crashes and a backup version has to be restored, we get emails asking about the apparent resurrection of creatures who the system had notified ‘parents’ had perished! The current online version that appeared in 1997 actually responded very much to our users, the suggestions and ideas they had about the site. One of its options provides statistics about the creatures. The direction we’d like to go is more towards the provision of a social space—chat spaces—which currently people find elsewhere, tracing one another via the directory of users on the site. Users have developed their own networks, have even met one another for sex, and discussion of their AL progeny…”

Like Waxweb, Technosphere has become an ever-evolving project. Commencing in the early 90s as an excursion into the sublime and the picturesque of a landscape piece, its latest manifestation has become a real-time rendered, 3D animation which enables the ‘critters’ to be individually tracked through the terrain in which their ‘parents’ have placed them. Based on a modest PC platform, the new version is a permanent installation at the National Museum of Photography in Bradford, England, but still seeks the cash and in-kind investment to become a fully distributable AL artwork.

Internal Organs of a Cyborg shifts into the more familiar territory of the strip cartoon, and the less familiar tribulations of a 12 year-old substance abuser and implant junkie. The paranoid obsessiveness of this interactive futurzine has us traipsing through framings of hospital corridors, film noir streets, the streak and blur of paramedics and emergency vehicles. As the mouse rolls over parts of these images, as images and sounds morph and cut to exquisite medico/scientific 3D animations of, kinda, body and machines, we struggle to build the meta-narrative from the fragments through which we stumble, refracted like William Burroughs’ words and Linda Dement’s images.

Working with interactives on screen, the user struggles to construct within their head frame a sense of the space in which this piece is operating physically. This is not narrative cinema, where we have become accustomed to fragmentation and seek to link the end of one storyette with the beginning of the next, to create a linear whole, out of which a geographical space emerges in plan form that connects what took place on screen.

In Cyborg, as for Waxweb and many storytelling interactives, because what we encounter is fragmented, we have little to go on for the purposes of reconstruction, or rather mental synthesis. We are not sited in the comfortable immersive space of the cinema experience, observing, reflecting, maybe interpreting, but within the flux of possibilities of interactive multimedia, assessing the shards of image and word collisions, and creating meanings and connections that interrogate, like the rhythms and cycles of a mantra, the lived experience of the subject.

David Blair: www.telepathic-movie.org; www.waxweb.org; Jane Prophet, Technosphere.

RealTime issue #33 Oct-Nov 1999 pg. 18