Political theatre re-activates

Mary-Ann Robinson

Polyglot, High Rise

Four recent Melbourne productions dig into hot political issues around diversity, exploitation and conflict. Using humour and acknowledging complexity, this kind of work reinvigorates contemporary, issue-based theatre.

Beyond the Gate of Heavenly Peace centres on young Chinese people in Australia trying to study, work and survive. Some are ‘illegals’, with expired visas. They change names to make it harder for immigration officials to locate them. ‘Johnson’ and ‘Lincoln’ share a flat with 2 young women. Amongst them moves an older man, the spirit of China, the Australian goldfields, the past of all Chinese.

The writing is strong and phrases are memorable: “The Chiko roll was invented by a Chinaman out for revenge.”; “Maybe we are better people in a foreign country.” There is no simplistic veneration of freedom or democracy contrasted with the repression of China. Characters are complex, not good, not what they seem, apart from some 2-dimensional Anglo characters.

Judy, a self described “Chinese princess”, lost a lot when she came to Australia to make something of herself. She collects the rent, does the shopping. She has contacts. Yet Judy tips off immigration when one of the others has an expired visa. Why? There’s less competition when there are not so many of us. She is ambivalent about returning to China, but cynically founds a ‘Melbourne-Chinese Pro-democracy Movement’, to which she has no commitment. As a result, she is accepted as a legal migrant. Playing the system works.

The rhythm of Beyond the Gate is the slow, regular beat of conventional theatre, with few changes in pace. However, a striking live music combination of violin and electric guitar works with the performers and video backdrop of Tiananmen Square, soldiers, and Melbourne freeways in the rain, to yield an insight into lives lived quietly, out of sight. This was director David Branson’s last work [see Obituary page 12].

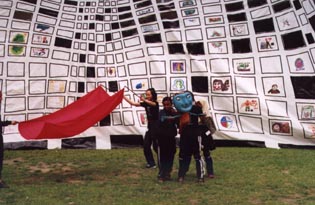

Polyglot’s High Rise—a puppetry adventure was based at the Carlton Housing Commission flats. High wind and belting rain drove Sunday night’s outdoor event indoors. Many performers and the bigger puppets remained outside. A lot was lost in this transition but the energy and engagement of all those involved was infectious, the audience drawn into a world of coping with adversity. Outdoors in Melbourne is like that.

A crowd of mainly non-residents jammed into a smallish space to see this classic community theatre piece: stories collected from residents dropped into a narrative device. A child chases her scarf one evening as it blows through various flats in the high rise. Stories are told by local gems like Johnny Shakespeare and Ernie Sims. Clusters of school children with wooden pigeon-puppets flap by as the scarf blows on to the next point. Brightly coloured wooden boats sail through as stories of dislocation from all over the world are told. The same old stories, but fresh and intense because they are true. You know the child is telling his mother’s story of walking across Somalia. You know he was born on that journey and his mother really lifted an abandoned child from the road and placed it under a tree because she couldn’t carry two. (A collective cringe as this child says his mother will never forget what Australia has done for her. So grateful. We’re probably all thinking of the others, the ‘queue-jumpers’.)

High Rise—the music, stories and puppetry—seemed to be owned by these people. Few teenagers, but that’s a different project. Perhaps the next step is to build something beyond these narrative devices which allow the telling of individual stories. Is there a new story that can be built and told through a project such as this?

Melbourne Worker’s Theatre’s Magpie program notes suggest another classic community project, earnest and didactic: a “reconciliation play”, exploring contact between Indigenous and non-indigenous people. However, beginning with loud Mambo (Mabo) music and jokes, the audience is drawn into a complicated world of hilarity and blackness, past and present.

There’s Captain Cook in full naval regalia, standing pompous in braid and hat, gazing into the distance, completely naked below the waist. Elsewhere, children prepare for an Australia Day parade. Little Moses wants to carry a spear. The teacher insists on clapping sticks. His friend ends up in a grass skirt, the ‘gentle natives’ amongst the awful cardboard tall ships and swagman’s hats. As we watch these snatches from times past and hear jokes from the MC—the black/white Magpie—we hear a terrible story. A middle class man (Henry) and his wife stumble into their lounge room, half drunk, in shock. He was driving. They hit someone. They panicked and fled. He drinks more. Should they call the police? They are immobilised by guilt and fear of the consequences of the terrible thing they have done. They left a young black man dying in the gutter. They try variations on the story: I wasn’t drunk. He stepped in front of the car. He was dead before we got to him. Someone else will stop and help.

Two stories interweave. This haunted couple react to the accident as we learn about the man killed. He was Moses and he had a life.

The action takes place in numerous sites, at times diluting the intensity through its distance from the audience—not so for audience members dragged on stage to sit in the “cheap seats”! Magpie generally avoids clichés. Moses does a stretch in prison, but just as you fear the vision of him hanging by a sheet, there’s a surprising turn. He argues with an inmate who wants a cigarette. Moses says the man should say sorry first. He refuses. They banter and fight. Fucken this, fucken that. Resigned, Moses hands him the cigarette packet. He takes one and then chucks the packet on the ground. They look at each other. The white guy picks up the packet, throws it at Moses and mumbles “Sorry.” These were electric performances pushing old arguments and tensions in new directions. The depth of exploration of these urban Australian lives includes full black/white humanity in what could have been political diatribe. Even the Anglo characters are interesting.

Secrets is the annual performance of the Women’s Circus. Eleven years on, people come out on a cold night and pay to sit in a big windy shed to see a play about sexual abuse. What does that say? We can handle politicised theatre when it is like this. A row of old offices high up at the end of this huge shed is painted as a little set of suburban kitchens. Doors slam. We hear shouting and see the peeking through blinds, seeing what goes on but saying nothing. Keeping secrets.

Below, the huge space fills with masses of women belting around at full throttle. Chants and songs blend the wildness of kids’ music with that sinister edge to childhood innocence in a world of dark secrets. Two beautiful clowns are old style ‘50s Mums’, trying to get on the trapeze without showing their undies, clutching handbags and gloves: feminine modesty as a historical joke, a physical gag. There are the benign, friendly adults on stilts towering above the kiddies in gingham dresses in the schoolyard. Then there are the other adults who come at night, in the dark: “There is a small spot on the ceiling and I am not here.” Women’s stories of abuse are told simply and elegantly in narrative or physical form. Stunning images include black figures hanging from blood-red tissue, spinning in huge space. Another image is of a woman climbing the backs of others and falling, defeated. A later mirror image of this event shows a joyful ascent and release as her body is supported, thrown into space, trusting, caught and held by others. Even the riggers and techies bring a physical beauty of their own in the fast and easy competence with which ropes are flung, dropped and caught up again. This circus has always been physical and political, but is developing their style of sophistication and patterning, evident in the writing and performance of Secrets.

To roll along on waves of laughter as you understand the losses of urban Aboriginal people; to bounce with joy at the physical exuberance of women who have been abused and told their tales and learnt to fly like children again. Old-style didactic theatre is too heavy handed for this stirred-up cultural mix. A newer, politicised theatre has caught up with the present again.

Beyond the Gate of Heavenly Peace, director David Branson, writers John Ashton & Jian Guo Wu, performers Lorraine Lim, David Lih, Warwick Yuen, Virginia Cusworth, Minming Cheng, Phil Roberts, Fanny Hanusin and Ronaldo Morelos, Carlton Courthouse, Nov 7-24; High Rise, a puppetry adventure, Polyglot, Carlton highrise flats, Nov 17-18; there will be a version of this project performed at North Melbourne Town Hall in 2002; Magpie, writers Richard Frankland & Melissa Reeves; director Andrea James; performers Lou Bennett, Richard Bligh, Syd Brisbane, LeRoy Parsons, Bernadette Schwerdt, Maryanne Sam, Melbourne Worker’s Theatre, ArtsHouse, Nov 15-Dec 1; Secrets, writer Andrea Lemon, director Sarah Cathcart, Women’s Circus, Shed 14, Melbourne Docklands, Nov 22-Dec 8, 2001

RealTime issue #47 Feb-March 2002 pg. 35