Give me space, and I'll give you the show!

Nigel Kellaway

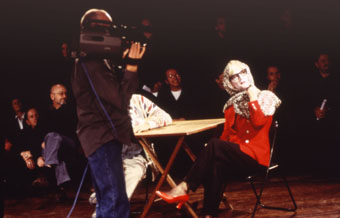

Peter Oldham (camera), Nigel Kellaway, The Audience and Other Psychopaths

photo Heidrun Löhr

Peter Oldham (camera), Nigel Kellaway, The Audience and Other Psychopaths

What follows is the text of Nigel Kellaway’s contribution to Scrapbook Live at Performance Space, Sydney, a series of presentations dedicated to the relationship between performers and the theatre and other spaces in the building for some 20 years (see Regrets & recollections: Sydney dance/performance 2001 in this edition for more on Scrapbook Live). Kellaway has performed in the theatre space with the One Extra Dance Company, the Entr’acte ensemble, The Sydney Front and performed with and directed The opera Project, as well as performing his own solo projects, The Nuremberg Recital and This Most Wicked Body. He knows the space intimately and seems to have exploited almost every one of its possibilities.

For his presentation, Nigel used one of the PS gallery spaces decking out the long room with suspended costumes or patterns or fragments of costumes: “Give me the frock and I’ll give you the show.” As each was lowered, he spoke of the costume, the show and its relationship to the theatre space.

* * *

My Name is Nigel John Kellaway.

I was born on the 30th September 195….I am an actor.

I have stuffed 20 or 30 dolls with the sawdust that was my blood.

Have dreamt a dream of a theatre in this country.

And have reflected in public on things that were of no interest to me.

That is all over now.

Well, no it isn’t–or so it seems not.

They were the opening lines of a production I co-performed in 1994. It wasn’t on this particular rectangle of floor.

It was in that other space, just down the corridor–12.67 x 22.75 metres, lighting rig at 5 metres.

The walls shifted from a very light grey, and darker and darker, to black over 20 years. It is that space that I wish to celebrate this evening.

In the 20 minutes allotted this evening, I would dearly love NOT to talk about MYSELF, but what has made the Performance Space such an extraordinary centre for the development of movement language over the past 20 years.

But that is not the brief–so I will glance at just ONE history that refers to a performer’s experience of this space.

20 years– the regular phone calls from Mike Mullins in 1983 at 6.00 of a Sunday evening–begging me to volunteer to make pre-show coffee–no kitchen or alcohol–just a kettle, some instant coffee and the gully trap in the courtyard to wash out the cups. (Mike was taking a rare evening off.)

Numerous short appearances, and 33 -35 full length works. (Lost track–the list [of productions detailed by the Scrapbook Live curators] in the other room has forgotten some also.)

What do I talk about? How do I edit?

Well how about a cliche? Nigel and his frocks (“Give me the frock, and I’ll give you the show!)

Well, actually there are only 9 (that I’VE worn)–and here are the remnants. Hardly representative of the entire opus– but they do comprise a kind of scrapbook–a glimpse–a ragbag.

The first one is hardly a frock–though it’s imbued with similar deviant persuasions…

It’s a kind of skin, a nudity (and that’s another cliche attributed to Nigel’s work–hey, you just put it on–it’s a bit foreign–you hide behind it–and it saves on the design and dry-cleaning budget.)

Nigel Kellaway, El Inocente

photo Heidrun Löhr

Nigel Kellaway, El Inocente

COSTUME 1: TIGHTS

At 8.00pm on October 14th 1981 some closely focussed lights came up slowly on 4 dancers (2 bare-chested men in flesh coloured footless tights, 2 women in matching leotards). Lynne Santos, Kai Tai Chan and two dancers making their Sydney debuts–Julie Shanahan and Nigel Kellaway.

The music was Bach.

The work was originally titled THE IMPORTANCE OF KEEPING COMPLETELY STILL.

Ironic, hey? Sounds a bit like a William Forsythe title, but we hadn’t even heard of him in those days.

Jill Sykes wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald:

“Kai Tai Chan is continuing to sharpen his ability to choreograph straight dance pieces, though this work doesn’t reveal much of an advance. The most accomplished dancer is Julie Shanahan, but everyone made a distinctive contribution.”

With a first Sydney review like that I knew I had a golden future ahead of me!

(Sorry Jill, although I don’t want to abuse your professional distance, I’m probably going to have to mention you on a few occasions this evening–you must surely have one of the longest histories of involvement in and support for the Performance Space. You have been here since that first night of my association with the Space, and probably before then–and there is just no getting away from you!)

And too often, all we have left of a show (as years pass) is a handful of reviews.

What else was happening in this city? What were our histories?

Graeme Murphy had recently transformed the Dance Company of NSW into his very own Sydney Dance Company.

Heiner Müller was ripping European theatre apart (though we really hadn’t heard much about it in those days).

We were trying to remember Heidegger’s Phenomenology, Jean Paul Sartre’s Existentialism.

Grotowski had already crippled a number of young Australian bodies, but teased them with one brand of enlightenment.

Some of us had heard of Pina Bausch, but it really wasn’t for another 6 months until that full hurricane of her influence was going to hit our shores.

Some of us were still wondering whether Baryshnikov was the greatest dancer ever born (the impossible is so alluring, isn’t it?).

Russell Dumas was playing to 30 or 40 people a year in his occasional Sydney appearances at the Cell Block.

There was an influx of artists and loose collectives congregating in Sydney at that time–some from interstate, some returning from Europe. And some notable locals finding a new voice.

And in Adelaide, at the 1994 Festival, Tenkei Gekijo performed the interminable Mizu No Eki (Water Station). Within a month Nick Tsoutas had Groteski Monkey Choir and several associates climbing ever, ever, so slowly over chairs to peer at a snowy TV screen in this space– call it appropriation if you wish, but we were being oddly activated by the foreign!

COSTUME 2: GIVE ME A ROSE

I survived an extraordinary 4 years with Kai Tai, launched myself as a director and then ran away immediately to Japan–not for the art– for love.

Not a word of Japanese and $40 in my pocket–but love does that to you, at a certain age.

But I was a diligent contemporary dancer and did my compulsory 6 months with Tanaka Min.

Until the fearsome Alison Broinowski (1st secretary at the Australian Embassy at the time) took me on a personal project– off to Suzuki Tadashi (I had never heard of him–neither had anyone else in Australia, except for Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter)–and some of Australia’s physical theatre changed a bit–The Suzuki rash, I call it affectionately.

Go all the way to Japan to rediscover the ancient Greeks!

I’m being frivolous, but this frock is the proof: Clytemnestra in Give Me A Rose To Show How Much You Care , January1986. It was all a bit of a surprise for Sydney audiences. I think they were hoping for something a tad more “Japanese”.

Taka, my partner, arrived from Japan on the morning I opened. He stuck with the show through the season. He didn’t have much English, but still managed the box-office and washed the stage floor every night. Cute, eh? Doubt he’d do it now.

But as you can see I practiced the art of serious applique. Don’t laugh–it was an apprenticeship for a long career of tight budgets.

COSTUME 3: WALTZ

In January 1994 The Sydney Front trashed its storeroom—almost everything off to the tip–a cathartic experience–just the odd wedding frock and crinoline survives.

The Sydney Front first applied to the Australia Council through the Dance Board–unsuccessfully. We applied a lot–always unsuccessfully.

Especially when we devised a project (63 actually) we later called The 63 Blessings.

We became, briefly, terrorists, but of a cuddlier variety than our recent friends.

This is a pattern for the costumes we all wore for our first work in 1987–Waltz.

$140 worth of black polycotton clothed all 8 of us. The cast cut them out and Mickey Furuya and I spent 2 days sweating over an overlocker.

Combined with our next work this became The Pornography Of Performance, and with that, The Sydney Front was well and truly launched.

We began with a handful of ancient Greek monologues, and via Peter Weiss, Peter Brook and Heiner Müller we arrived at POST MODERNISM –it took us ALMOST by surprise!

The Sydney Front went to Brisbane–Expo 88–7 fucking months all together in the same house–2 street parades, on stilts, 7 days a week.

COSTUME 4:NUREMBERG

It was time to re-find an individual voice!

The Nuremberg Recital, 1989–a solo work.

Jill Sykes described it as “an economical 50 minutes”.

Don Mamouney pronounced me Australia’s greatest clown–in retrospect, that was quite nice–perhaps even accurate!

But, at least I mastered the art of burying a zip–hand stitched–not a bad job at all–for a first try!

Simon Wise designed the lights, Chris Ryan stage-managed, and Sarah de Jong (the composer) arrived with the opening 10 minutes of music at 7.45 on opening night

–but she DID drive me to the airport at 9.00am after the closing night bumpout for The Sydney Front’s first European tour.

I LOVE COMPOSERS!

The Berlin Wall fell—and The Sydney Front took a year off.

COSTUME 5: DON JUAN

Ah, Don Juan, 1991!! My personal favourite of all The Sydney Front shows.

The first frocks for The Sydney Front that I didn’t have to sew myself. Thank God–nothing I sew would survive 120 performances

–the show hung around for 3 years. John Baylis and I drank a lot over those years.

We were both apprehended, after one performance, by a security guard close to our hotel in Soho, London, as we emptied our bladders on an apartment wall late one night. Threatened to call the police. We were of course outraged by the prudery. “Fucking Poms” we spluttered.

We may have been derelicts, but we had some seriously good reviews in our pockets.

COSTUME 6: FIRST AND LAST WARNING

First And Last Warning , 1992

Hey, there are 200 of these [slips worn by the audience] stored between my and Clare Grant’s roof cavities in Newtown.

We even invented a size 28 (had them especially designed for Eugene Ragghianti, Leo Schofield, et al).

Mine was a size 12, and I can still squeeze into it (perhaps not the prettiest sight–though it probably never was).

I was feeling a bit shitty at that time (had no idea in those days what “anxiety disorder” meant) and demanded that I was not going to perform–well at least not until the last 10 minutes when I could have the stage totally to myself (what a prick!).

I sang a song and then reminisced about all the famous people I’d met (I was practicing the “embarrassing moment”). Nureyev, Pope John Paul 1st, Frank Thring. They’re all dead now.

Which leads me to reflect on where my peers from 1981 are now. Most of us are still alive but not many of us are still regularly practicing. Australia is not that comfortable about performing artists over the age of 40 tackling anything too adventurous. Try to name 5 contemporary performance artists actively creating fulltime, in Sydney, over the age of 50.

But sorry, I’ve digressed.

COSTUME 7: THIS MOST WICKED BODY

The work that I quoted at the beginning of my presentation was from This Most Wicked Body, 1994.

I incarcerated myself in the space for 10 days–nearly 240 hours, and danced, shouted, flirted, ate, fucked and slept a little.

I toiled over the presentation of a person I was not. The work was, rather, about what a space, THIS SPACE, could (might) create and nurture–a troubled man, a man in crisis, a man possessed.

It was a celebration of a very special theatrical space–a space in which the wonder and beauty of the body can be shown in all its grubbiness–boldly, no apologies– a body that can say “I hate myself”, “I hate you”–and then say sincerely and humbly “Thank you”.

Indeed, this space is the Mecca of both License and Indulgence.

Jill Sykes wrote: “Kellaway delivers all this in a deadpan voice, varied only by the number of decibels. His body is the more eloquent of his communication skills, emerging here in its most specific form of ballet, with its symmetry and strict turnout, and the inward-turning irregularity of butoh.”

(Sorry, Jill. I’m only quoting the irritating bits from your reviews. You’ve also written enquiringly and positively about my work over the years–and for this particular work you drew out many of the essential dilemmas posited.)

What did The Performance Space represent? Sarah Miller [former Artistic Director, currently A.D. PICA. Perth] and I were both serving on committees of the Performing Arts Board of the Australia Council at the time. I reflected on and argued for what HYBRID practice meant–it all seemed second nature to US–how come no-one else seemed to be quite cottoning on? We wanted recognition for not only OUR process, but one that was emerging all over this continent ……. and it was soon tucked away under the banner of New Media.

What a cop-out! I was nurtured by an environment in this space that allowed me to explore beyond one particular sphere. This was not just a dance space, it wasn’t just a gallery, or a theatre space. It was a place of dialogue. And that impact on individual artists doesn’t happen overnight–it takes years–many of them quite unconsciously–you learn new processes–slowly.

COSTUME 8: TOSCA

Ah, TOSCA!!!

My first opera Project frock–Annemaree Dalziel designed–and I only got to wear it for 10 minutes.

What does The opera Project want? An ensemble of artists–our peers–those we share knowledge with. It has to be flexible–that suits both the artists and the funding bodies. Perhaps what The opera Project has succeeded in doing, if nothing else, is to draw mature artists back to the Performance Space on a regular basis– back home.

Our “opera” is about the body and the space we find ourselves in.

In this building it is always the same 4 walls.

The feet are placed– the arms reach out– they lead the eyes.

A pyramid, grounded on this floor, and yet in relationship to the extremities of the blackened space and the imagined beyond.

Think about the Pyramids of Giza.

They were built by humans–with vision and skill. But they weren’t created in a moment–it took hundreds of years of transferred knowledge.

It’s always an issue when one makes work about culture, rather than about society of the distilled “NOW”. Performance Space has, over the years, balanced both these issues.

I am in an environment where I am drawn to talk to people. People even talk to me!

I’m an artist enchanted by 19th century opera, the movies of Luchino Visconti and his ilk, point shoes, good Italian tailoring…

….and at the same time I’m committed to contemporary hybrid performance.

Weird–but I feel comfortable.

Katia Molino, Nigel Kellaway, El Inocente, Performance Space, opening May 2

photo Heidrun Löhr

Katia Molino, Nigel Kellaway, El Inocente, Performance Space, opening May 2

COSTUME 9: EL INOCENTE

El Inocente, 2001.

What a tragic rag–I made it–I don’t do pretty these days–I do drab–it’s so much less stressful.

Poor Katia Molino and Regina Heilmann– they had to wear identical costumes— but then, of course, those two women would look beautiful in anything.

Due to certain vagaries in the levels of government funding, an extraordinary patience was demanded over 3 seasons (2 of them developments) and 18 months by the Performance Space and its audience.

After the eventual bona fide opening night this year, Tess de Quincey asked me when the trilogy might be performed again. I immediately assumed that she was referring to our Romantic Trilogy (The Berlioz/Tosca/Tristan). But no, she was talking about the 3 showings of El Inocente–all a bit different, and all staged in a single evening, demonstrating a process.

I thought the idea ridiculous (as well as impossible), but I have to acknowledge that for so many people associated with this space, the “process” is incredibly important–and there is belief that “process” can be celebrated and performed in a satisfying and theatrical manner.

We won’t ever do it–but Tess had articulated a concern.

Colin Rose in The Sun Herald would beg to differ: “the dullest, most humourless and most pretentious hour I’ve spent in the theatre for many an evening–Kellaway makes a ridiculous spectacle of himself … and a question for Kellaway: does the word “tosh” mean anything to you?” Frankly, Colin, NO. But top that for inspirational comment – perhaps only James Waites in RealTime …

But, hey!, I won’t go on.

CODA

It’s not just the press!

The dance world, too, is a hideously vicious world, where-ever you might be. It promotes a culture of the body, and that is an intensely personal vision. Young children are drawn into this culture, and gaze endlessly at their image in the studio mirror–a scary inward vision. This is a culture of “me, me, ME!”.

I have listened to dancers scream for 30 years about the lack of support and camaraderie in their profession, and then watched them stab a colleague in the back. I’ve done it myself.

The Performance Space introduced me to a sometimes different world–a dangerous world, but a potentially supportive one. Any dance artist who has been associated with this space is a privileged one.

My anecdotes are personal– My work is public–That is all that matters. My work acknowledges various extra-theatrical issues–but it comes back to one simple concern–my work is about a body (sometimes several bodies).

That space (out there!) has allowed me to move that body and my imagination. I have been a musician, an actor, a dancer–a body. Only THAT room would have permitted me such freedom.

I have worked many other spaces that have insisted that I stand still– that I define my practice in a brief sentence. It’s too easy, as you tour your work or processes to other contexts, to appear radical and fresh in that foreign climate with its different histories and experiences. But the demands are actually greater when you strive to entertain/provoke a similar/familiar audience over 20 years. It’s not just preaching to the converted–it’s attempting to invigorate an often jaded palate.

I’m a notoriously lazy person, but this space has demanded that I keep moving.

And so to you and a thousand artists (some of whom I’ve never met), those who have contributed to this extraordinary space: I very occasionally hate you, but more often I love you.

THANK YOU.

Nigel Kellaway, Scrapbook Live, Performance Space, Sydney, Sept 30

RealTime issue #47 Feb-March 2002 pg.