BEAP: interactions, intersections

Melinda Rackham

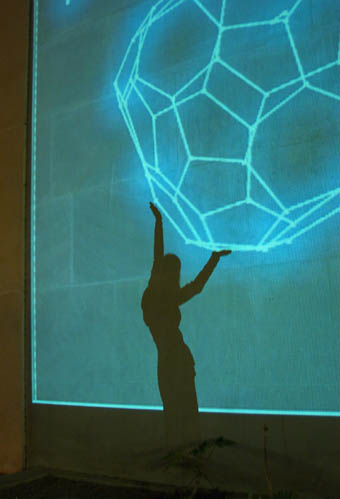

Victoria Vesna & Jim Gimzewski, Zero@Wavefunction, nano dreams and nightmares

The first Biennale of Electronic Arts Perth (BEAP), directed by Paul Thomas, had an ambitious multi-threaded program encompassing 3 exhibitions, along with several conferences, forums and symposiums, seeking to both present electronic artworks and investigate their theoretical and philosophical aspects.

BEAP’s themes, including biotechnology, consciousness, locality, virtual reality, and alternate and experimental modes of projection sparked debate, with many artists and theorists at the CAiiA-STAR Consciousness Reframed Conference focusing on notions of reality and how interacting with electronic arts alters consciousness. But what does this actually mean in practice? Immersion, curated by Christopher Malcolm at the John Curtin Gallery, responds by showcasing electronic installations from both Australian artists and Internationals (mostly associated with CAiiA) whose practice deals with interaction, artificial intelligence, portals and alter-realties.

The main gallery was dominated by the elegantly simple Zero@Wavefunction: nanodreams and nitemares, a collaboration between Victoria Vesna and nanoscientist Jim Gimzewski (both USA). The artwork’s interactivity is based on the way a nanoscientist manipulates an individual molecule billions of times smaller than common human scale but projected on a massive scale. The viewer stands in front of a tonal projection casting a larger than life shadow which activates the software nano-molecules or buckyballs. These respond via sensors to the movement of your shadow, changing shape and direction so that you can manipulate the molecule through the interface of your body. The resultant human interaction is incredible: normally staid audiences lose their self-consciousness and jump, dance, and move their arms and bodies to shift and alter the projections in a truly immersive virtual shadow play.

On the opposite end of the scale of ethereality is Ken Rinaldo’s Autopoiesis where we are spatially engaged by 10 giant metallic and vine branch robotic arms or tentacles suspended from the ceiling, moving in response to gallery viewers and each other’s movements. The artwork/organism modifies its behaviour over time. It’s silent when the gallery is empty, however when one enters, the arms jump into action like synchronised swimmers, or Star Trek borgs communicating with each other via audible telephone tones. Rinaldo’s work also places our bodies in dialogue with what seems to be alien intelligence—bringing into focus the symbiotic relationship between biology and technology.

Nigel Helyer injected some contemporary political content with his subtly minimal sound installation Seed. The gallery audience utilises headphones attached to land mine detectors to hear the exoticised Arabic music emitted from small mines placed on mini Persian carpets. Other Australian works included Chromeskin, the result of a 3-year collaboration between west coast artists Richie Kuhaupt and Geoffrey Drake-Brockman, and Lynne Sanderson’s Somnolent Fantasies. Stelarc was well represented, from documentation of his 1970s skin piercing performances through to his current technologically augmented practice, with the sculptural metallic Exoskeletons of his performances on display—works that make it obvious that electronic arts have antecedents in performative art practice.

Skylab was another collaborative work, a 3D video installation by Biennale advisor David Carson with 3-D video artist Brian McClave (UK) and George Millward, a UK based atmospheric physicist and experimental electronic musician. Dealing with regional issues, it was viewed through 3D glasses, evoking a cosy retro cinematic feeling. The large-scale back projection created a mesmerising Turell-like space, where image and text free-floated with astronauts, combining NASA footage with local media snippets detailing the fear of space junk falling onto Perth.

Even more locally based was Screen, an exhibition of WA artists curated by Pauline Williams situated over 6 locations across the city, as well as tucked into a long corridor at John Curtin Gallery. This limited space on the way to the toilets was utilised to great advantage by Rebecca Dean, Paul Caporn and David Fussell with their blue lagoon video, performance and text installation, documenting love gone wrong against a background of idyllic palm-tree wallpaper scenes in individual toilet cubicles.

Screen also previewed the new CD-ROM (strangely categorised as an “interactive film”) from Perth producer Michelle Glaser (see RT48) and a talented production team. The psychoanalytic Dr Pancoast’s Cabinet de Curiosities has a 1920s illustrative aesthetic reminiscent of a medical textbook. The viewer is quickly engaged by exaggerated mouse movements, either pulling phallic-like objects or rubbing the mouse furiously to move to new screens, find more information, or stimulate sex organs. Via this voyeuristic screen frottage we enter the doctor’s intimate arena of naïve erotica viewed via keyholes and peep shows. His phantasies immerse his patient, a certain Miss Smith, in a carnivalesque atmosphere of exquisite caricatures and evocative soundscapes. It feels nicely naughty, and again on the collaborative thread, is best viewed with a friend.

BEAP was not without teething problems. The geography of Perth and the scattered locations of events, as well as the CAiiA conference being held in 2 venues, meant a lack of cohesion, some confusion, and hours of daily travelling for conference delegates. Additionally, the restrictive opening hours of John Curtin Gallery meant it could not accommodate the large audience for the major drawcards, Canadian Char Davies’ Osmose and Ephémère, the best-known Immersive Virtual Environment works available today. These ground breaking breath-navigated, individual head-mounted display worlds from the mid 1990s rarely travel because of the expense and the logistics of their installation. Simply extending gallery hours, or at least opening on Saturday, would have made them more accessible to both local and visiting audiences.

Then there was the glaring divide between the space and resources allocated to installation and screen-based work. BEAP Director Paul Thomas’ belief that net.art doesn’t belong in a gallery meant this medium was not well represented. This was unfortunately demonstrated by the staging of Robert Nideffer’s (USA) online proxy.com and creepycomics.com as a short series of slides projected high in a tiny room. Proxy.com (http://www.nideffer.net/homey.html) is a great online work, however it takes time for individual set-up and to acquire the skills to play. I highly recommend viewing it online as it immerses you in a world of electronic characterisations and interactions. However it was a poor curatorial choice in this context, as it does not lend itself to casual gallery viewing, which many other online interactive pieces are specifically designed to do.

Overall BEAP was a very successful event celebrating electronic arts and developments in science, technology and philosophy. It did bridge the ambiguous spaces between the audience and the artwork, providing alternate modes of interaction and engagement. As well, the focus on interaction is a timely reminder that, as galleries and museums start to acquire electronic works, they are best valued by their shared experiential potential rather than as discrete objects. By coming to terms with its staging problems and omissions BEAP in 2004 should be an event to look forward to.

Biennial of Electronic Arts Perth (BEAP), July 31-September 15, www.beap.org

See also Stephen Jones on BEAP.

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. 11