Who stole 'craft'?

Kevin Murray

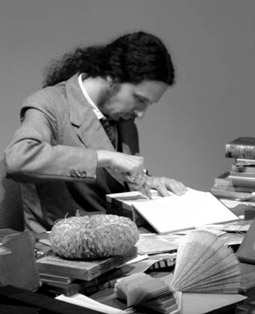

Nicholas Jones

photo Kevin Murray

Nicholas Jones

“Can I borrow a dictionary?”

Coming from Nicholas Jones, this seemingly innocent question struck terror in my soul. Jones carves books. A book to Jones is not a respected repository of knowledge, it is a raw substance ready to be transformed into a 3-dimensional work of art—a thing in itself. Using a scalpel (his father was a surgeon), Jones cuts through the raw pages to expose the stippled texture of the print. It’s a craft that Jones has largely invented for himself.

Jones was resident in a program called Open Bench, staged so the public could witness the theatre of craft process. Visitors could be seen pleading with Jones to save certain books that were lined up for his scalpel. Now he’d come into my office to “borrow” a dictionary.

“No, you’re not having it.”

“I just need to find a word.”

“You’re not having any of those words. They all belong in the book.”

Reducing books to their physical substance has the consequence of objectifying words as things to be possessed rather than shared. In a literal fashion, Jones is threatening what appears to be happening linguistically around the country. A word is being systematically removed from our official lexicon. That word is ‘craft.’

In titles of courses, exhibitions and magazines the word ‘craft’ has mysteriously disappeared. In its place is the much more happening word, ‘design.’ To an extent, this seems to be a natural evolution—design is the provision of objects for personal use in ways that reflect contemporary scale of manufacturing; design is simply an opportunity to capitalise on good craft. Isn’t ‘design’ just an updated form of ‘craft’?

But one suspects a sleight of hand. Take the case of a recent name change at the National Gallery of Victoria. With its move into Federation Square, the prestigious triennial prize exhibition titled Cicely & Colin Rigg Craft Award was renamed the Cicely & Colin Rigg Contemporary Design Award. It’s a neo-modern title for an ultra-contemporary building. But it doesn’t quite fit. In fact, designers themselves were excluded from the original selection process. Calling what is produced by weavers, textile printers and artists who featured in the exhibition ‘design’ takes our attention away from the process of construction. We are led instead to think about function, style, networks and product. The expressive capacity of these works is disabled.

Why is this happening? Some might see it as a sign of the creeping commercialisation of our cultural institutions. ‘Design’ provides a cover by which resources can be channelled away from the ‘drain’ of culture into the ‘investment’ of business. More apocalyptically, it may be seen as part of the escapist consumer culture that is seeking to transcend the physical world, whether through speed, screen or 4 wheel drives. This kind of ‘design’ is the ever-expanding monoculture of global elites. Don’t get me wrong. As far as monocultures go, design is wonderfully exciting—but it is perfectly able to stand in its own Nike runners without government assistance.

Whatever the reasons for the design push, it is for many a matter of concern. While arts funding has remained relatively true to its cultural mission, there is always the threat of commercial imperative.

But panic would be the wrong response. It is within exactly this kind of adversity that the craft ethic flourishes. In New South Wales, the Craft Advocacy Group has been militating against the decline of services for craft practitioners. In Victoria, anonymous missives called ‘squirts’ have been circulating with enigmatic demands such as “10% for craft.” But these ventures have limited success. While fuelled with a defiant spirit, such attempts sometimes become too absorbed in a righteous opposition and miss the opportunity to win minds as well as hearts. They play to the stereotype of craft as a reactionary movement, initiated by those clinging to the 1970s.

The fact is that craft is growing in new directions. In addition to the core of dedicated professional craft practitioners who maintain the skills and creativity of their medium, there are new energies coalescing around the applied arts. Craft has been embraced by the emergent ‘no logo’ generation, sceptical of the pre-packaged meaning of branded objects. Clothes are deliberately badly made—hems are skewed, sewing is wonky and edges are frayed. Hand-made is a sign of liberation. In Melbourne, the Stitches & Bitches nightclub knitting circle has become a legendary way for women to exert their gender in a testy environment.

In the new ‘hand-made’ push, craft is more about expression than skill. In the case of ceramics, a new generation has eschewed traditional pottery skills such as wheel-throwing and developed new forms of idiosyncratic expression. Sydney ceramicist Nicole Lister uses casting to give disposable objects a solid form. Melbourne ‘mud-maker’ David Ray gives the suburban table a Dresden-like ornateness. These makers shadow consumer culture, giving it a meaningfulness it would otherwise lack. Some go so far outside traditional skills that they end up inventing new crafts themselves, like Jones. The fascination with making will continue even in the absence of tradition.

The place of craft in the context of visual arts is also evolving. As a material art, craft becomes pivotal in the dialectic between the screen-based practice of artists like Susan Norrie and Patricia Piccinini, and the physical expression of painting or sculpture. These days painting has more in common with ceramics than it does with the ubiquitous video installation. Already in England, ‘craft’ has become a code for reaction against the celebrity YBAs famous more for their lifestyles than their art.

In the case of photography, the digital processes have inherited the mission of reproduction, leaving the darkroom with the alchemic remnants. We are beginning to see crossovers between craft and darkroom photography. Janie Matthews uses darkroom-like processes to print rust. Kirsten Haydon has produced a wonderful bridge printed on a grid of old metal slide containers. As the emergence of photography led to impressionism in painting, so the introduction of PhotoShop is generating a new craft of photography.

This does not put craft at odds with the digital world. Collaborations where the physical process of making incorporates the digital in a more intimate form are beginning to emerge. Also emerging is the use of craft as a lingua franca between indigenous and modern worlds. Contemporary visual art and design takes us further away from where we are. In Australia, the moral responsibility of place has been passed on to Aboriginal culture, leaving global classes the freedom to belong elsewhere. Your average minimalist urban living room is beautifully offset by the rough edges of an Indigenous basket. This ‘enlightened’ regard is merely another version of primitivism, where the remote culture is made exotic and dialogue avoided. It realises the ironic bargain invoked after the fall of apartheid: “You can have the crown, but we’ll keep the jewels.”

By contrast, craft is one of the few opportunities for reciprocal exchange between Aboriginal and Balanda (non-indigenous) people. The ever-growing Alice Springs Beanie Festival demonstrates how the humble craft object can bridge cultural divides. This festival has inspired others, such as the Melbourne Scarf Festival, which includes workshops in Islamic scarf-wearing.

So, even if they have stolen the ‘craft’ word, it’s only a matter of time before we find it again. The ‘design’ word is becoming so over-used that it is losing any reference beyond a short-term political kudos. The new ‘craft’ will be discovered as harbinger of a future utopia beyond the screen, promising a new existence of responsibility and enjoyment—a place they call the ‘real world.’

RealTime issue #54 April-May 2003 pg. 29