Justine Cooper: new media alchemist

Keith Gallasch emails Justine Cooper in New York

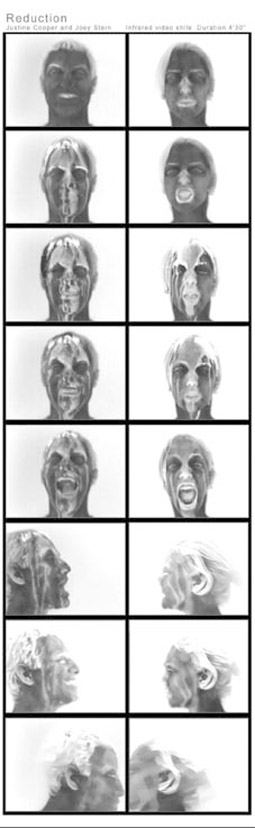

Justine Cooper, Reduction

“Moist is a video created using light microscopy. I use blood, phlegm, pus, cervical mucus and tears—fluids with emotive qualities—to translate out the biological self into meteorological or interstellar geographies.”

MAAP in Beijing 2002 catalogue

Justine Cooper is a leading Australian new media artist who has been working productively at the nexus of art and science with some outstanding creative results. Back in 1998 an image of her foot, scanned using Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the work titled RAPT, appeared on the cover of RealTime 26. RAPT attracted great attention (Cooper writes about the work in the Tofts, Jonson & Cavallaro collection, Prefiguring Cyberculture, Power Publications, 2002). She has subsequently created a number of significant works and exhibited internationally in over 30 shows in 12 countries across 5 continents, most recently as part of MAAP in Beijing 2002 with the large scale video work Moist, and this year at the International Center of Photography, New York and the Earl Lu Gallery, Singapore. As well 2 of her videos have been exhibited this year at the Julie Saul Gallery in New York. Reduction, a striking video work for 2 performers was part of the Another Planet collection of Australian video curated by Keely Macarow (see review RT 54) and shown in Chicago and New York.

It’s fascinating to see you working in a variety of formats from gallery installation to animation, with performers, to creating components for use in live performance. How have you arrived at such a diverse way of working?

My first encounter with the collaborative process was at the age of 5, in the surgery room of my parents’ veterinary clinic. I opened sutures, squeezed the bag on the anaesthesiology machine, powdered gloves and kept my eyes open. It only took another 25-30 years before I went back to the ‘theatre’ for a collaborative work called Tulp with Elision [the Brisbane-based new music ensemble] and composer John Rogers.

I was commissioned to be the visual director. But in general I try and match an idea to a medium, and that’s partially led to working across disciplines. I like the sense of alchemy that comes from combining varying sets of skills and fields.

Is there a unified aesthetic behind these impulses and creations?

The more work I make the more I begin to see my own patterns or themes returning in different incarnations. Sometimes the connection is fleeting, but it gives me a sense of the matrix I’m working within. I think there is an aesthetic of pacing. The rate at which elements move and unfold has a certain consistency, even when one piece is quite abstract, and another one is more narrative.

You have been strongly associated with science in your work. What is the connection and the inspiration for you—awe, critique, the artistic potential?

My interest in science has evolved. RAPT used a medical technology, it didn’t use science. That’s a distinction not always made—science versus the technologies of science. RAPT came out of an interest in trying to map a shift in the way technologies (not science) affect our concepts of space and time. That was a rather large supposition to make. But I’m not doing science, I don’t have to prove anything, I don’t have to have consistent results. I don’t have to ask how? Rather I can interpret in anyway I choose: I can ask why?

So I attempted to define that cognitive shifting through the prism of the body. What I mean is that we are accustomed to the physical boundaries of our physical selves, and they are fairly consistent from one individual to the next. So it was a natural starting point. I then exploded that physical body via technology. RAPT both disrupts time—in the animation the body is built and dismantled—and space. In the installation you can walk through my thorax, for instance. So I saw the artistic potential, and it was a natural fit to use a machine (MRI) built for bodies. Scynescape and Moist used other forms of imaging—SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy) and light microscopy, respectively. Both ‘processed’ and created the content through imaging systems used in science. Scynescape maps the external body at high magnification while Moist used bodily fluids, but both rebuild a corporeal landscape that is unfamiliar.

I absolutely think there is an aesthetic quality to these visualisation tools. If you talk to histologists [cell and tissue scientists] many would say they were attracted to the field in the first place because it is so ‘aesthetic.’

If I were to talk about more recent work, like Transformers, there I actually start to build content that engages with ideas from science, particularly molecular biology and genomics. And the body that I’ve been using all along stops being my own (as representative of a universal one) and starts becoming a body with individuality—an identity.

There is a more critical element to Transformers because the subject is loaded. How is identity a merger of science and culture? There’s an element of intangibility and contestation there. It can’t be locked down into a percentage. There’s not an empirical assessment process. Any time you broker a relationship between two or more entities there has to be a real assessment of what’s at stake, what the benefits are, where’s the added value?

How did you go about creating your video work, Reduction, with the performers and with what technology?

Reduction was a collaboration with Joey Stein. We had access to a thermal infrared camera, which registers heat. If you look closely you can see the tracery of veins and arteries running beneath the skin. While it is a camera, it must be connected to a computer to actually interface with it. We needed to control what was going on within a very prescriptive framework. So that was one consideration in making a performative piece: we could choreograph it.

Each performer was shot separately with the idea that this could actually be a 2 channel work, the channels on side by side monitors or screens. That type of presentation would accentuate the ambiguity over whether the characters are trying to communicate with the audience or each other. The ‘language’ they use is pretty responsive and primal. Originally we were looking at dead or near extinct languages, and then ended up layering another ‘aural performance’ over the visual track, where the sound is created by recording the performers responding with a small delay, which was then re-aligned in post-production.

What is the value to you of working in New York?

New York is difficult in terms of accessing facilities; or rather it takes longer. However it does have a much stronger tradition of philanthropy and corporate giving. A work like Reduction can be done at little cost, but the projects I am interested in developing now are more ambitious, involving public spaces and large technical and equipment costs. My hope is that I can make them happen. I didn’t come to New York simply because there is more money here—the cost of surviving here is considerably higher after all. There are opportunities, though, and I feel I’ve been very fortunate in both Australia and New York. I see my path as more of an orbit, moving through both places on a regular basis, working on projects in both countries.

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 4