All in the timing

Virginia Baxter talks to Leisa Shelton

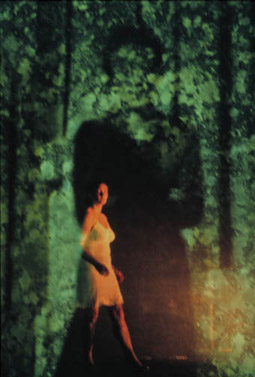

Leisa Shelton, The Inhabited Woman

photo Heidrun Löhr

Leisa Shelton, The Inhabited Woman

Three weeks before she begins rehearsal of her new work, The Inhabited Woman, Leisa Shelton and I are talking about timing. When she announced it, some colleagues wondered why she would be leaving her teaching at the VCA now, after 4 and half successful years. Surely, this is where it all pays off? Then there was her decision some years back to have a baby at which time friends said, “Why would you do that now, when your career is taking off?” And again, in 1989, after training in Europe for 6 years, she decided to return to Australia, she asked herself: Is this the right time? As worlds were opening—Bausch, Kantor, Mnouchkine? Then again, this was a good time for Australian performance—Lyndal Jones’ Prediction Pieces, Jenny Kemp’s Call of the Wild. Having chosen to stay, she looked around to see talented dancers working up solos in scout halls with no opportunities to perform.

But for Leisa Shelton each decision has turned out to be in some way timely. She feels a sense of achievement having been at the VCA in an era of shared vision with a team that included Richard Murphet and Robert Draffin, under the directorship of Lindy Davies. Her response to the Sydney artists’ dilemma in the 80s was to start Steps a curated program of physical performance at Performance Space which showcased the work of an extraordinary generation of performers including Roz Hervey, Kate Champion, Matthew Bergan, Sue-Ellen Kohler, Nikki Heywood and Anna Sabiel. And the baby? Well little Audrey is the envy of her playgroup. How many other kids have kept time with de Keersmaeker from their mother’s lap?

LS My background has always been physical theatre more than pure dance which is really what Steps was about and working with Meryl Tankard in Canberra (1990-93). If I was going to be called a “dancer”, I wanted to push open a bit what I knew dance as being from my training and work in Europe…And in Robert Draffin and Richard Murphet’s work the language is derived from the physical state or the physical manifestations of the being inside the world.

I see the training of an actor as being, from its base, physical but the approach is very wide and it’s internal far more than external …the internal is affected kinesthetically and physiologically. Ultimately the one thing that all good theatre training eventually comes back to is the breath and the breath is a physical act. It’s still a contentious issue—what is physical and what is vocal. Breath belongs in different areas in different ways. It’s a bit like water in the world.

Which is extremely contentious—apparently we’re in for a bout of water wars. In 2000 you collaborated with Richard Murphet on Dolores in the Department Store (see RT43). Does your new work together spring from that?

In the form, yes. The Inhabited Woman is a concept that I’d started work on when I was awarded the Rex Cramphorn Scholarship. (1993) The originating question remains: What are the voices and worlds that inhabit a woman as she wakes?

And how have your answers changed since your original conception?

At that stage I was in my early 30s and it was an almost preoccupying focus for me to have a child. The whole process was very fulfilling. But as I came out of the early baby time, the reality of having a certain career trajectory or momentum and being the mother came into real conflict….The ability of the 2 to function together I found was a myth. I started to read about other women….I became caught in what this was about, this expectation of “having it all” and the reality of, in some ways, being left with nothing.

While someone like Simone de Beauvoir set up a context in which contemporary women could see their lives, and could claim self again, in order to do that and to uphold her place in the mythic relationship with Sartre, she paid a very high price. And I guess between 35-40 [for me] a lot of things changed very quickly. That became a time to question what you can and can’t do any more and how you find the point of balance, the moment when you can say it’s enough. I am this good a mother. I’ve done this much work that I’m proud of….I can personally sit with that. Then I have these moments when I’m caught in or overwhelmed by a certain perception which says, Ah but…what you could have done!

How is the woman “inhabited” in the work?

We started with a series of provocations and from that Richard has written the language…The metaphor has come from some reading I’ve been doing about the death of Virginia Woolf, her drowning, which I always found fascinating—that a woman could walk into a river, lie down and stay there.

With stones in her pockets.

A few. But not enough to hold her down. The water was very shallow, thigh high. She put herself under the water and lay down and drowned. The will and the need for that release was so intensely present in her that she could do that.

So the piece begins with a dream of walking into a river and submerging and staying under. The river returns throughout the piece and remains the metaphor for the woman’s desire to be something other, to go somewhere other, to inhabit a watery underworld. And the desire which the river continues to force forward and out of her, the sound of the river, the memory of the river, the return of images from the dream [all] force this desire inside her, out and into her home.

I wanted very much for this to be about the internal world of a woman which can be calmed and nurtured, or its difficulty be enhanced, by certain circumstances. But I wanted the woman’s world to be good. She is with a good man. She has a small boy of 3 who loves her. She has a beautiful home. She has all she should need and want. She should be happy. It’s enough. And for her it’s not. And it’s not about being in an abusive relationship, or difficult financial circumstances. It’s about a world inside her which is being denied. And the river forces it out of her. And she has to leave that world and find herself. She checks in to a hotel where she could be anyone and there she meets herself.

You have a team of young artists on the production working with film (Elspeth Tremblay) and sound (Katie Symes) and architect Ryan Russell. How do those elements work within the piece?

The river is entirely sound and image. At the moment, the film occupies the woman’s internal world or the perceptive world from outside. The dream is shown in film. Her imaginal world is projected in the space on a variety of surfaces at the same time as her inhabited state is present in the room. One of the ideas we’re working on is that when she finally does enter the domestic space—in which there is no man and child, just the voices of, sounds of—the film will show how the man sees her move through the room. The other side will show how the child sees her. In the middle is the woman who is neither one nor the other.

This is quite a task for a male writer

It’s like in Asian theatre when men play women because they understand them. They’ve witnessed them, watched them. Obviously the women that Richard Murphet has been in continuous contact with have affected what he’s witnessed…The writing for the women in Dolores… was glorious. His ability to write the minute detail, the complexity of the internal world is one of the layers of [his] Slow Love [1983, 2000] that I love. I always found it surprising that a man had written that. And The Inhabited Woman is very provocative, contemporary feminist writing, written by a man. And some people may have a huge issue with that. But I actually love it that a lot of that language hasn’t come directly from me. I’ll interpret it in a world in which we’ve chosen the elements together.

Is this exclusively a female experience you’re dealing with?

It’s inside a lot of men too. I don’t think it’s a mid-life crisis point but I think it affects a generation of women who are having children later, who have tasted a certain level of autonomy and self-driven life choices who find it very difficult. It’s a big thing for a woman to walk out of a family. So the struggle is to find a point of equilibrium. And I don’t think the examples are there. It’s ‘give in entirely and be this’ or ‘let go entirely and be this.’ But if you’re trying to tread the 2, then you’re just disappointing everyone.

Personally I feel like it’s an area that we’re not managing to cater for together at all as women because it’s layered with a certain level of guilt and desire to prove we can do it. And it’s all getting bottled inside us as we all try to make it work. Everyone’s watching to see who’s managing to make it work or failing to do so. And for others it’s the not-having-had the child that’s the constant….so that having had the child seems like you did the good thing without realising what it means to have had the child. So there’s no easy ground…And this is not an autobiographical piece—much as it terrifies me to realise how close, particularly over the last 3 years, the material of this work is—some of it is absolutely not my experience…I wanted to investigate the other, not go to the autobiographical place…and I have no answers. This piece unfortunately doesn’t answer things for anybody (WE LAUGH).

Expect something far better than answers in The Inhabited Woman.

The Inhabited Woman, Leisa Shelton, Melbourne Town Hall, June 19-July 6

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 9