Collective imagination: et al.

Simon Rees

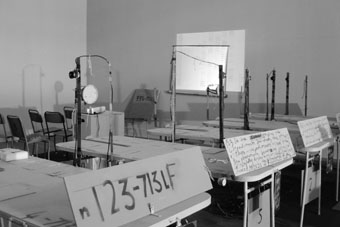

et al., serial_reform_713L (2003), installation view Govett-Brewster Art gallery, New Plymouth

photo Bryan James

et al., serial_reform_713L (2003), installation view Govett-Brewster Art gallery, New Plymouth

Prime Ministers in Australia and New Zealand rarely have anything to say about the work of artists. Likewise parliamentary debate hardly ever focuses on contemporary art, let alone individual practices. The memorable exceptions to the rule are the furore surrounding the acquisition of Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles (1952) by the National Gallery of Australia in 1973, the purchase of David Hockney’s A Bigger Grand Canyon (1998) by the NGA in 1999, and the gift of Colin McCahon’s Victory Over Death II (1970) to the same institution by the New Zealand Government in 1978. The latter example sparked debate on both sides of the Tasman about McCahon and his work.

Recently, the selection of the artist collective et al. to represent New Zealand at its national pavilion at the 2005 Venice Biennale provoked a parliamentary and media debate. Despite the rule of “arm’s length funding governance” (common to Creative New Zealand and the Australia Council), in her joint role as Prime Minister of New Zealand and Minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage, Helen Clark publicly criticised the selection.

Like Australia, New Zealand is in an election build-up, so any topic can quickly become controversial. And for a murky set of reasons et al. were made over as public enemy number one by a range of competing parties in politics and the media. The collective’s chief offence seemed to be that Joe journalist and Joe parliamentarian just didn’t get it. Clark, who claimed the arts portfolio on the strength of her love of opera and orchestral music even bowdlerised Ad Reinhardt’s ironical ruby: “I don’t know much about art, but I know I don’t like installation.”

Reading between the lines, what united the antagonists was a belief that any artist going to Venice needed to take on an ambassadorial role for the country’s art and to some extent, the nation. By extension the work in question should possess a healthy and identifiable degree of “representative-ness.” Yet et al. refuse interviews and make conceptual, not representational work. Herein lay the problem.

Et al. is a group of some 25 artists including minerva betts, lionel b., marlene cubewell, merit gröting and p mule. Best known to Australian audiences is contributing artist L budd, who presented work at the Bond Store in The readymade boomerang 1990 Biennale of Sydney. That exhibition concentrated on avant-garde movements and makers, with the focus on Dada and Fluxus providing a rich association for et al.’s practice and their emphasis on group production, installation and performativity. The catalogue entry was illustrated by a diagram that formed a target around a cluster of artists’ names. At the bullseye were listed: Tretchikoff, Norman Rockwell and Andrew Wyeth. This page work, which listed, among others, Pro Hart, was a catalogue of kitsch, eliding L budd’s antecedents and producing dummies, not doppelgangers. And the accompanying essay was an extended textual elision, a poem not prose essay containing every bad-faith idea about art that could be crammed onto a catalogue page. We were none the wiser.

This tendency has continued in the 15 years since that Biennale. In 2003 the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery worked with the artists to present the major exhibition et al. abnormal mass delusions?, encapsulating 20 years of work. Rather than take the form of a survey show—that would be too easy—the artists gathered materials from collections, studios and stockrooms around the world to make an environmental installation encompassing the work and re-editing it in new and exciting ways.

To start with the entire museum was painted “budd grey”, a harsh institutional colour prepared especially for the collective, that hovers somewhere between battleship grey and what we might imagine the world of Kafka’s autocrats looks like. (A false floor was laid, and painted, so that the visual effect was totalising.) Restricted access was the first installation encountered when entering the museum. A hurricane fence marked off the gallery in which it was installed from the viewer, and objects were heaped in piles to form a gestalt: there was no easy way of individuating works. The dominating objects were a building site porta-loo, a suitcase turntable playing a symphony and a set of antique speakers blaring a braying donkey (the call sign of the artist p mule). It was disconcerting for viewers to say the least.

The heaping of works in Restricted access was a hegemonic disavowal reflective of the way the collective resists singular identification. As such, it was a perfect introduction to the world of et al. The collective’s work spread, virus like, throughout the building in a concatenation of wires, obsolete audio-visual machinery, computers, scrawled text, furniture, books and aural bombardment.

The exhibition culminated in the new work serial_reform 713L (2003), a chamber filled with rickety institutional office furniture, angry green glowing PCs, a projection of scrolling digits (part random maths, part master code) and panels emblazoned with psycho-babble. With wires trailing across the floor and the harshest and loudest soundtrack within the building, the work emanated a malignant aura. Its referent was the outer limits of Soviet psychiatry and mind control experiments: the stuff that fuelled McCarthy-ite paranoia and films like The Manchurian Candidate (1962). Its subject was (probably) the continuing drift of the telecommunications, computer and media industries, not to mention government, towards mass duping.

Judging from the outcry from politicians and journalists mentioned at the commencement of this article, the tough aesthetic and honed critique touched a nerve. The will towards reiteration and editing has continued since abnormal mass delusions?. The porta-loo had new life breathed into it as Rapture at the Wellington City Gallery in May-August 2004. This time it was a self-contained installation, the major element of which was a massive and subterranean rumbling soundtrack that made the loo and the gallery shake to the core. There was also a small effigy of a mule and a projection of a computer plotting a sine or sound wave. The soundtrack comprised underwater recordings of the 6 under-ground nuclear explosions conducted by the French government in 1996.

Rapture is a cogent reminder of a disaster waiting to happen on our doorstep, and the evil of military technology at a time when threat and fear have been banished to the Middle East. Venice will hopefully provide et al. with another rich vein of architecture and history to tap into, and an opportunity to reconceptualise their shifting practice in even more remarkable and unremitting ways.

et al., the fundamental practice, New Zealand Pavilion, Venice Biennale, Italy; June-Oct 2005

RealTime issue #63 Oct-Nov 2004 pg. 6