Documentary: Illuminating the dark

Simon Enticknap

The President Versus David Hicks

There’s an air of hopelessness and sad failure permeating the subject matter of this year’s AFI documentaries which, nonetheless, makes for some very good films. At the end of Helen’s War: Portrait of a Dissident (director Anna Broinowski), the war in Iraq is continuing and any sign of peace or imminent worldwide nuclear disarmament seems far-fetched; Lonely Boy Richard (director Trevor Graham) concludes with Richard Wanambi heading for a long stretch in prison (and, depressingly, looking forward to it); and the absent subject of The President Versus David Hicks (directors Bentley Dean and Curtis Levy) is still in limbo at Guantanamo Bay. Then there’s Mart Bakal and Vincent Lee in The Men Who Would Conquer China, (director Nick Torrens) representatives of a new wave of Sino-capitalists who confidently expect their latest venture in China to propel them towards billionairedom. It doesn’t seem fair somehow.

The Men Who Would Conquer China is the outsider in this year’s selection. It has no Australian content; Mart is a New York banker, Vincent is a Hong Kong financier and, by and large, that’s where we see them operating, apart from various excursions to Chinese provinces where they inspect businesses ripe for outside investment/plunder.

Both Mart and Vincent have their own motives for wanting to capitalise on China. Mart wants to make some serious money but he also has a startlingly naïve conviction that globalisation is good and that the world is a better place for being branded and homogenised in an American form. Vincent wants to be rich too, but he must also please his father and establish a position for himself in the upper echelons of the Chinese business and political system. To a degree then, their agendas differ and the film works well when it reveals their personal antagonisms and frustrations with each other.

Equally, it doesn’t seek to glamorise the business of capitalism, which mainly seems to consist of sitting around in boardrooms, on planes, at various dinners and banquets. There is obvious wealth here but it’s not the wealth of consumption. Rather, it’s a restless, blind impulse to find new formations, to buy and sell. Mart and Vincent are nominally in control of this process but are also beholden to it. Torrens’ film benefits from a familiarity with the protagonists but nevertheless maintains a low-key critical distance.

There’s a telling scene early in Helen’s War when Dr Helen Caldicott encounters dozens of copies of Mike Moore’s Stupid White Men in an American bookshop, but only 2 copies of her latest book tucked away on the shelf. The anti-war movement has a new voice, a media-savvy, multi-skilled populist. “We’re saying the same things,” exclaims Caldicott, “except he’s funny. Well, I’m funny too.” Except she’s not. Caldicott doesn’t do funny. She’s driven, passionate, uncompromising, fearless and deadly serious, because these are serious matters: the destruction of the planet, the end of life as we know it and the prospect that Melbourne will end up looking like it does in Nevil Shute’s On the Beach, the book that started it all for Dr Caldicott way back when. She made a name for herself during the big anti-nuclear campaigns of the 1970s and 80s, but is anybody listening now? Does anybody care?

Broinowski’s film follows Caldicott as she tours the US trying to find an audience for her message, fighting for airtime and coverage, drumming up support. Caldicott’s views don’t change, she knows that she’s right and everything that happens is exactly as she predicted, but there are still shifts and new strategies. A book promo tour becomes an email campaign and a think-tank with some heavy-duty sponsors. Caldicott shows she can still cut it and there is poignancy in seeing her rage against the bomb, confronting a mortality that is both personal and global.

Lonely Boy Richard (RT58, p. 17) is a well-measured and considered piece about the impact of alcohol on remote Aboriginal towns in the Northern Territory. Without sensationalising or over-dramatising the subject, the film displays great empathy and patience, taking what could have been a throw-away news story and producing an insightful, albeit painful, portrait of a man, his family and a community.

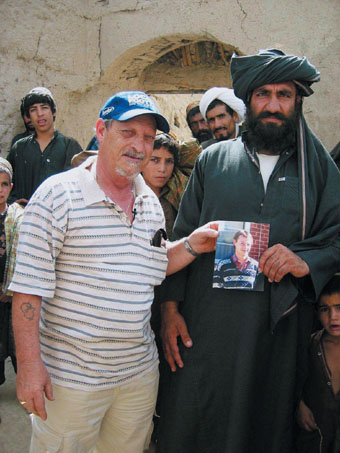

Dean and Levy’s The President Versus David Hicks has been widely distributed and needs little introduction. It is a chronicle of the times that uses the absent David Hicks as a prism for examining how ordinary lives can be touched and transformed by worldwide events. While everybody is implicated in the conduct of states in the ‘Global War on Terror’, Hicks is at the pointy end where its impact is most stark and pitiless. His father, Terry Hicks, steps into his son’s awful void and the film is as much about his journey as it is about retracing David’s.

Caldicott, Wanambi, Hicks, Bakal and Lee—this year’s documentaries are all about contemporary life stories of personal struggle and endeavour. Its pertinence and pathos should win The President Versus David Hicks this year’s award. Despite their general gloominess, this year’s films see Australian documentary filmmakers intelligently and sometimes provocatively engaging with the key issues affecting all our lives on the planet today.

RealTime issue #63 Oct-Nov 2004 pg. 23