Notes from a floating world: ISEA2004

Lizzie Muller

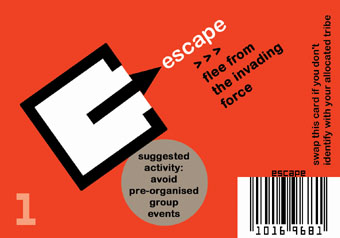

Leon Cmielewski and Josephine Starrs, Floating Territories game card

I am standing in the departure hall of the Helsinki ferry terminal. Long lines of new media artists, theorists, curators and funders queue alphabetically to check-in for the ISEA2004 (Inter-Society for the Electronic Arts) Baltic cruise. Among the passengers are many well-known names whose thoughts dominate the email discussion lists and websites that underpin the new media art community’s sense of identity. And here they all are in the flesh; the network embodied.

At 4 o’clock we set off. Outside it is pouring with rain. Those artists with work on the ‘sundeck’ look hassled and soggy; they’ve had 3 hours to install their complex artworks from scratch. Inside water is pouring in from the roof onto the DJs and slopping out of the hot tub over the floor. Surely it is not a good idea to mix so much electronic art with so much water. There is art everywhere; on the ferry’s television system, in the lifts, in the gym, even in the pool. But at this point it’s difficult to tell the difference between what is working, what has been broken by the rain, and what is still being set up.

The first artwork that makes an impact on me is Josephine Starrs and Leon Cmielewski’s Floating Territories. Each passenger has received in their conference pack a small card with instructions. I’ve got “Petition: sway opinion towards your own position—buy an influential person a drink.” I compare with someone else nearby, who has: “Converge: meet on safe ground—invite someone to collaborate.” There is a computer component to the work that maps personal family migratory history, but it is the cards themselves that are most interesting in this context. In their self-referential irony our instructions expose the solipsism of the new media art world, in which the behaviours we value—networking, collaborating and theorising—have become a kind of tribal dogma and a recipe for isolation, rather than engagement with people outside our field (or boat). The work alludes to the “floating world” prints which celebrated the sensual and artistic pleasures of 19th century Tokyo during its period of isolation from the rest of the world. In our own floating world we are getting our fair share of sensual pleasures as the evening wears on.

On deck 10 at Club Stardust, artists have taken over the karaoke machine. By midnight everyone is dancing in the ballroom and people are diving in the hot-tubs; the passengers are partying like it’s 1999. As I watch the new media art world frolic I wonder what this surreal knees-up says about this community’s self-image right now. It has an air of grand folly that implies self-confidence and a sense of reaching a certain zenith in development. Has new media culture reached, as Tapio Makela, Program Chair, writes in his rationale for organising this big party: “a stage where it has the maturity to be both sensual, technically advanced and critically aware”?

The major theme of the event, “Histories of the new”, also indicates an arrival at a key evolutionary moment, a point from which we must look back and take stock. New media art is canonising its heroes, pointing to its past, claiming its hard fought right to be taken seriously. As if to prove this point, that evening at the performance of Séa.nce, by Norie Neumark, Maria Miranda and Greg Turner, we summon our collective laptop emotion to conjure up the spirit of Marshall McLuhan. “Who wants to ask Marshall a question?” asks Neumark. Someone types into the chat space: “Marshall, can the network save your life?”

On day 2, I begin to try and plan the speakers and events I would like to see. The event is enormously ambitious, over programmed and complex. Apart from the overarching history theme there are 7 others: “Wearable experience”, “Wireless experience”, “Networked experience”, “Interfacing sounds”, “Geopolitics of media”, “Critical interaction design” and “Open source and software as culture”. There are more than 300 presentations, picked from 1,300 entries by an international programming committee of 40. Once I have cross-referenced the theme I’m interested in against its timeslot and location, I begin to see the uselessness of planning in the face of such chaos. I decide to follow my nose and take my chances.

The networking, at least, has become more systematic. There are official times for African, Asian, French and New Zealand network meetings. My nose-following strategy proves successful, leading me to the interesting Asia-Pacific session which highlights the problems and tactics of networking within a massively disparate region where many governments are either indifferent, or hostile, to collaboration with their neighbours.

The discussion foregrounds the topic of the “Geopolitics of media”, which really comes into its own in Estonia. We arrive in Tallinn on day 3, partied out and sleep deprived. Program co-chair Mare Tralle welcomes us with a reminder of how Estonian access to media and technology has been affected by politics. She describes the “void of media” left in the wake of the Soviet era, followed by the “e-euphoria” of 1990s Estonia, which was mixed with the “ultra right-wing political turmoil of regained independence.” She hopes that ISEA2004 will engage the Estonian public and provide “international reference points for re-assessing our local situation.”

We have 2 days in Tallinn. The conference venues are a 30 minute walk from each other, with simultaneous programs, and there are 4 exhibitions around the city. This leg of the journey is more like a hit-and-run collision than a profound engagement with Estonian culture.

I steal an afternoon from conferencing to pay some attention to the major exhibition, which explores the “Geopolitics” theme. Many of the works create or expose undercurrents of social and political exchange, such as Sarai Media Lab’s Network of No_Des, an absorbing hypertext world of found material from the new media street culture of Delhi. The show is an interesting portrait of international practice, but all the texts are in English—none are in Estonian.

The last leg of our journey brings us back to Helsinki and the opening of the major “Wireless experience” exhibition at Kiasma. I am weary of this wanton mobility. I don’t feel wireless and networked—I have never felt so encumbered, leaden and difficult to transport. In spite of myself I am cheered up by the first piece I see: Rebecca Cummings and Paul Demarinis’ Light Rain. My umbrella, which has been an unhappily overused companion on this trip, becomes a delightfully imaginative interface, resonating with melodies transmitted by an artificial rain shower.

One piece in the show goes down particularly well with the audience. Bubl Space by Arthur Elsenaar and Taco Stolk is a “concept device” that blocks mobile phone signals for 3 metres around the user. People queue up to try making a call near the device and are delighted when they can’t. What a good idea: poor us, all we want is a little bit of personal, communication-free space in the urban landscape.

Day 6 dawns and the adventure is nearly over. I am looking for synthesis, a way to draw meaning from this chaotic experience. Of course, when you go looking for synthesis you usually find it, but a keynote speech from Sarai Media Lab’s Shuddhabrata Sengupta called “The remains of tomorrow’s past, speculations on the antiquity of new media practice in South Asia”, gives me something richer. He begins charmingly, self deprecatingly, by telling us that if you put an Indian behind a lectern he will tell you he invented the world. It is a timely reminder that any view of anything can be only partial. His talk offers “speculations about the possibility of constructing alternative, non-transatlantic histories of ‘new’ media practice.” He draws together the threads of history and geopolitics and puts his finger on the source of what has been worrying me since we set off on this journey, what he calls the “immature solipsism of the North American and European media scene” and the making of an historical grand narrative of new media art. He weaves a story of the development of a touch-based system of telegraph in 19th century India with the internet, giving them a common point of inspiration in the Buddhist texts of “Indra’s Net”, a legend of a net with a jewel on each intersection that creates an “infinite reflection process.” His point is not to suggest this is the origin of modern communication technologies, but rather, to show the viability of alternative stories to prove the opposite: “nothing comes from just one place.”

Sengupta offers a solution: the proliferation of stories and versions, “an open source alternative history.” A resistance to the synthesis I am seeking. Suddenly the chaos of the past few days seems a positive quality, and I don’t feel the need to search for answers or order any more. It has been a crossing of divergent paths that can be grasped only subjectively by each person present. I’m content to go home with my own story of what happened at ISEA 2004, to read the catalogue and marvel at the things I missed, to hear the stories of others who seemed to have gone to a completely different event.

ISEA2004, Baltic Sea; Tallinn, Estonia; Helsinki, Finland; Aug 14-22

RealTime issue #63 Oct-Nov 2004 pg. 34