Malthouse: vision and delirium

John Bailey

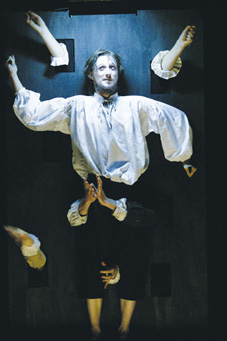

Matthew Whittet, Journal of the Plague Year

photo Lisa Tomasetti

Matthew Whittet, Journal of the Plague Year

Ham Funeral & Journal of the Plague Year

Though Max Gillies’ The Big Con was the official titleholder, it was The Ham Funeral and Journal of the Plague Year which really inaugurated Malthouse Theatre’s first season since its transformation from Playbox. Both shows opened in the same theatre on the same day, featured the same cast and, perhaps most importantly, the same director: Malthouse’s new Artistic Director and very visible face of the overhauled company, Michael Kantor. After the many changes announced since his appointment, this was the opportunity to see precisely what sort of theatre Kantor is committed to producing.

The more striking of the 2 works was Plague Year, written by Tom Wright after the story of the same name by Daniel Defoe. The play is structured as a series of tableaux covering 12 months in the plague-infested London of 1665, and features Robert Menzies as Defoe, guiding us through a society whose external sickness is mirrored by an internal decay. The rest of the ensemble take on multiple roles as denizens of this Dante-esque world.

One of the difficulties posed by the task of adapting Defoe’s tale stems from the original’s status as a kind of mockumentary: billed as journalism, many of the text’s stylistic devices exist almost purely to test the credulity of its reader. An abundance of trivial details, diagrams and first-person reminders of the narrator’s position as a kind of embedded reporter work to bestow an aura of authenticity. Lacking this requirement, however, the staged adaptation struggles to find a reason to include such devices; Wright must not only convert Plague Year to a new medium, but reinvent its generic setting as well. In fact he inverts the original by shifting it into the realm of the fantastic.

In freeing Plague Year from its original meanings, there is the danger that it will not find anchor elsewhere. Though a vague air of allegory permeates the production, it isn’t clear how we are to interpret the significance of events, an especially peculiar fact considering that a fatal pandemic plague has such obvious metaphorical resonance. Contemporary events are occasionally invoked (a passing reference to biological weapons, for example), but these potentially fertile references are rare.

Kantor’s ‘more is more’ approach sees the employment of a bewildering array of theatrical modes: mask, dance, farce, song. There is a sense that the real theme motivating directorial choice is simply the theatre itself as a vehicle for the production of wonder. If this is the case, Plague Year is an unabashed success. However, I find it slightly (though thrillingly) problematic that this production relies on an apocalyptic vision to achieve its effects. Apocalyptic visions can be seductive: lacking the psychological intimacy of tragedy, they instead use impersonal destruction to connote cleansing, starting over, even the possibility of rapture. Certainly, the mounting chaos engulfing Plague Year’s narrator is played out with ecstatic abandon, at one point incarnated as a very literal carnival. Here Kantor and Wright’s earlier work with Barrie Kosky’s Gilgul Theatre is revealed. Kosky has long been an exponent of carnival, grotesquery and excess.

The gleeful, heterogeneous vulgarity of Plague Year is echoed in the excesses of The Ham Funeral, but is moderated by the play’s iconic status as a misunderstood moment of shocking modernism in Australian theatre history. Viewing the work now, one can’t help but measure it against that which came before its controversial 1961 opening in Adelaide. More damagingly, one must compare it to what has appeared since. It’s not an especially challenging work to audiences weaned on absurd irony, black humour and alternatives to realism. It’s still a powerful piece of writing though, with Patrick White’s control of language shining through from the first lines of dialogue. The Ham Funeral is White doing his best Peggy Lee: if that’s all there is, then let’s keep dancing, break out the booze and have a ball. It’s revelry borne of despair, though there are times when this dips dangerously towards undergraduate angst.

An anonymous Young Man (Dan Spielman) moves into a squalid hotel/rooming house run by the basement-bound Mr and Mrs Lusty, a bloated, gluttonous pair. When her husband dies abruptly, Mrs Lusty announces a grand funeral featuring the titular ham, a dramatic absurdity which doesn’t bear quite the same vulgar connotations it may have when White first penned the play in 1947.

The performances are uniformly strong: Dan Spielman brims with confidence in a daunting role, inhabiting the character while retaining its ambiguous status as stand-in for White himself. In contrast, the rest of the ensemble tackle their roles with a vigour verging on the (entirely appropriate) hammy. Julie Forsyth and Ross Williams are the grotesque landlord and lady of the Young Man’s lodgings, and their bawling, belching banter carries most of the piece’s comic weight. Forsyth’s Mrs Lusty is a delirious rendition of the monstrous feminine, the antithesis of the somewhat ridiculously angelic woman upstairs (Lucy Taylor), whose disembodied voice and spectral presence obsesses the Young Man. He finds his libido pulled in contrary directions by carnal Lusty and her lofty, intellectual opposite–the symbolism is laid on with a trowel. The Jungian figuration of these and other characters comes across a little creakily, and this is perhaps the one area in which White’s script has not aged well. At the same time there is a joyous eulogising of outdated theatrical forms. The Young Man asks us “Is this a tragedy, or just 2 fat people arguing in a basement?” The answer to that question, I expect, holds the key to your appreciation of the piece. Both Journal of the Plague Year and The Ham Funeral are actors’ pieces, and it would seem that the new Malthouse is very much an actors’ theatre.

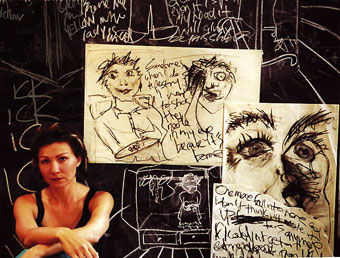

Anita Hegh, The Yellow Wallpaper

photo Peter Evans

Anita Hegh, The Yellow Wallpaper

The Yellow Wallpaper

Another work which used a classic text as the launching point for a performance testing the boundaries of theatrical convention was Anita Hegh and Peter Evans’ The Yellow Wallpaper at The Store Room. The slim volume written by Charlotte Perkins Gilman in 1899 offers us a narrator confined to her room for a “rest cure.” We are made witness to her slow descent into madness as the room’s wallpaper begins to take on an hallucinatory life which mocks and mirrors the woman’s own incarceration.

Hegh’s performance is all in this production: a plain set and simple lighting allow us to focus on her hypnotic portrayal of a woman driven to hysteria by patriarchal dictates. If the style of presentation is not overly embellished, neither is it minimalist: Hegh’s monologue is occasionally interrupted by pre-recorded voiceovers continuing the narrative, and at times she dons a pair of sunglasses and grabs a microphone to continue her tale as a spoken word slice of punk protest. The performance is note-perfect, reverent to its source but willing to stray from it, illustrating the power of the performer to reinvest texts with new meanings.

Journal of the Plague Year, writers Tom Wright after Daniel Defoe, director Michael Kantor; performers Julie Forsyth, Dan Spielman, Lucy Taylor, Ross Williams, Robert Menzies, Marta Dusseldorp, Matthew Whittet; The Ham Funeral, writer Patrick White, director Michael Kantor; performers as above; Malthouse Theatre, April 11-May 8

The Yellow Wallpaper, based on the novella by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, director Peter Evans, performer Anita Hegh; The Store Room, Melbourne, March 15-April

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 pg. 29