Abstraction. Sick.

Darren Tofts

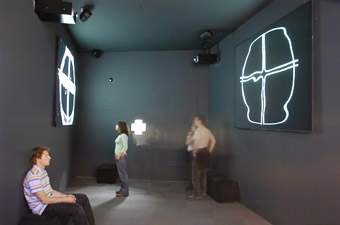

Bosch and Simons, Aguas Vivas (2002-2005)

photo Christian Capurro

Bosch and Simons, Aguas Vivas (2002-2005)

… art is not necessarily expression. – Samuel Beckett

What would be the ultimate compliment for an exhibition devoted to abstraction in the digital age? A ripped remix of key phrases by Ihab Hassan or George Steiner on the aesthetics of silence, a surround sampling of Susan Sontag’s styles of radical will? No. In the early 21st century, abstraction is sick. Let me tell you why.

White Noise is an overpowering and considerable sensory experience. Curated by Mike Stubbs to showcase the “ongoing relevance” of abstraction in the contemporary art world, it brings together a range of Australian and international works that explore the impact of ‘new media’ on the concept of abstract art. The installation of the works has been astutely designed to maximise our experience of the untranslatable, tantalising illogic of sense at the heart of abstraction. Visitors descend into the Screen Gallery and enter a darkened cabinet of curiosities to be explored via a vertiginous corridor of illuminated frames. Within it, glowing didactic screens recede to a vanishing point, drawing us in like knowing sentinels. The art seems to have already begun. On my first visit to White Noise I shared the experience with a cacophony of primary school kids. One of them disappeared into an installation. Immediately there was an exclamation of such import that I thought he had entered a portal to another world. “Sick!”

And he had. This is exactly what a show like White Noise should do. It should be confronting, intriguing and memorable as an event for the curious and informed alike. This kid had clearly encountered something that was unlike anything he had ever seen or heard before. And may never again. And he had experienced it in a context that was just as engaging and otherworldly as the most chilling ride he went on at Movie World last holidays. The work in question was Peter Bosch’s and Simone Simons’ Aguas Vivas (2002-2005), a mixed media installation in which perturbations on the surface of a moving drum of oil are captured simultaneously as real-time video and still images. If asked what it meant he would have phoned a friend.

For the critically informed cognoscenti of abstraction, White Noise was a bit of a mixed bag. The talking point was undoubtedly Ryoji Ikeda’s spectra II (2002), a beautifully unnerving, immersive work that accommodates one visitor at a time in a ritual of solitude. The journey through a darkened, claustrophobic corridor is punctuated only by the occasional pulse of sound and strobing light. The work’s encroaching terrain samples, in miniature, the architectural topography of White Noise as an enigmatic walk through sensory stimulation, the experience of which is always solitary, beyond communication and thus purely abstract. Another stand-out work was Black on Black, White on White (2005) by local artist Jonathan Duckworth, a beguiling, minimalist exploration of the limits of perception, in which the viewer is challenged to wrestle with the polarisation of light itself. Keiko Kimoto’s Imaginary Numbers (2004-2005) is a visually stunning journey into the metaphysical conundrum of nonlinear systems, which produces a series of dynamic portraits of the beauty of chaos.

On the down side there was a lot of similarity in terms of changing colour fields, data streams and pulsing lights. There was room for variation, too, in the selection of artists. It felt a bit like an Ulf Langheinrich mini-retrospective, with 3 of the artist’s works represented. Which isn’t to say that I didn’t appreciate their presence. Drift (2005), a work commissioned by ACMI, was an isometric workout for the senses. High resolution imagery of glistening octopus flesh writhes strangely on the screen. This is the most illustrative image to be found in the entire exhibition. As it morphs slowly into abstraction, it reveals the infravisible weirdness that haunts all representation.

For me the most pleasing component of White Noise was the Abstraction Now collection of online projects (a series of works originally exhibited in Vienna in 2003). The work here, too, was mixed and, in some instances, little more than exercises in the style of abstraction. But what was most satisfying about it was the assumption of digital literacy in its projected audience. There were no didactic panels alerting us to the fact that these were ‘interactive’ works. Nor, for that matter, was there any sense in the works themselves that explanation was required, either directly by way of instructions to the user or in their aesthetics. From the point of view of abstraction we should expect nothing less. From the point of view of media arts culture nor should we either, as such work should by now be accepted as part of contemporary art; especially so in the context of ACMI’s curatorial commitment to interactive works. The haptic lexicon of point and click, scrolling and rollover was thoroughly subsumed into the interaction, eliciting a dexterity that has become second nature in the age of the human-computer interface. This allowed for a deeper exploration of the works in the context of the exhibition’s thematics, rather than awkwardly foregrounding them as media art works that still require explanation and justification.

White Noise admirably reinforces the long-held tenet of abstraction that art doesn’t have to be about something to engage an audience. The street will always find a use for such things. It is to be hoped that White Noise is a sign of things to come at ACMI, which has the opportunity to cement its curatorial place as a space of bewilderment as much as certitude, exhibiting work that confounds and confuses every bit as much as it pleases the eye, or satisfies the desire for narrative. Recently a cabinet containing Stanley Kubrick’s Oscar for 2001 and his 1997 Golden Lion was installed at the entrance to White Noise. A cabinet of an altogether different kind. I presume it was a commercial for the forthcoming exhibition of the auteur’s archives in November, rather than a reassuring emblem of order in the midst of dangerous abstraction. For the time being anyway abstraction rules, okay. Sick.

White Noise, curator Mike Stubbs, Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Aug 18-Oct 23

RealTime issue #70 Dec-Jan 2005 pg. 24