Innovations for the ear

Samara Mitchell engages with Project 3

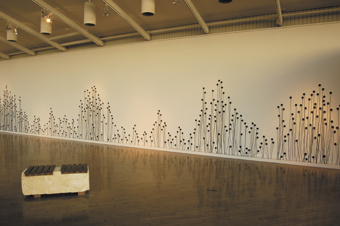

Robin Minard, Silent Music

photo Paul Armour

Robin Minard, Silent Music

She churns the contents of her bag around like lottery balls in a cage, looking for the keys to her apartment. Her uncapped lipstick stuck with bag-grit hits the circular staircase winding back down to the foyer, wet with second-hand rain from dripping umbrellas. A small maintenance-bot passes, climbing above her as it polishes the balustrade. Unlocking her front door she is greeted by an intimate composition of insects and trickling water quietly broadcasting from tiny speakers, fashioned within a Nouveau frieze of audio-poppies that adorn the stairwell and reach for the light streaming from a rooftop window.

Project 3 is an ambitious and provocative showcase of contemporary and historic electronic arts presented by the project’s artistic director Michael Yuen and produced by Three Reasons. Building upon an existing repertoire of works and ideas emerging from Projects 1 and 2, Yuen’s program encompasses a series of sound installations, performances, artists’ talks and public projections as part of the 2006 Adelaide Festival of the Arts.

Sonic Space

At the opening night of Sonic Space—Project 3’s concert of contemporary and iconic modernist sound compositions—I was immediately drawn to an installation of delicate matt-black speakers and cabling that climbed the pristine white walls of the ArtSpace gallery. Silent Music has travelled around the world in various guises, developed by the renowned Canadian-born composer and public sound-artist, Robin Minard. Formally the work simulates life on a variety of levels from poppies in tall grass to a cluster of single-cell organisms. Leaning in close to this exquisite installation, you hear a multi-channelled composition of water and insect sounds trickle from the ornate field of speakers. Like the designers and architects swept up by Art Nouveau in the late 19th century, Minard seems to have taken inspiration from the natural world without disdain for the artificial. In the wake of research into Artificial Life, Silent Music is a poetic response to the propositional complexity of inorganic nature.

The concert opened with Black Aspirin, composed by Christian Haines. Soaked and wooden sounds descended from ceiling-mounted speakers, like heavy drops of rain striking eaves, gutters, or instruments left out of doors. It is difficult to resist the temptation to compare these sounds with meteorological events as they affect the listener physically in the same way that elemental forces do. At one point during the piece, a storm cloud of audio above the audience bottomed out and a ferocious downpour of carefully orchestrated white noise ensued. An elderly woman in the front row clamped her hands over her ears, clearly not coping with the assault on her senses. Although the sound grew louder at this point, I don’t think the audience was beleaguered so much by the volume as the deluge of audio layers. Surrendering to a piece like Black Aspirin is an exhilarating, transforming and strangely comforting experience: like listening to a torrential rainstorm from the vantage point of your own lounge room.

The evening proceeded with a selection of historic experimental works pioneered by composers such as Conlon Nancarrow and Alvin Lucier presented by Tristran Louth-Robins. Nancarrow, a contemporary of artists such as John Cage and Elliot Carter, toyed with the inherited traditions of scoring musical events. It may have been his former career as a typesetter that drew him to experiment with the musical machine language of the player-piano, which he did almost exclusively in his later years as a composer. Audiences attending the concert were treated to a rare delivery of Nancarrow’s work on a pianola, or player-piano, specially acquired for the program. Dubbed as “impossible music” due to its polyrhythmic complexity, it is rare to see Nancarrow’s player piano works ‘live’ outside a musical conservatory or museum. Beginning with a style reminiscent of music-hall theatre, a Nancarrow piece may swiftly spiral into contrapuntal orchestrations on the exceptionally free end of the jazz spectrum. Whereas one can imagine a phantom player at the keys in the early stages of Nancarrow’s composition, such a ghost would need to grow extra arms, legs and perhaps even a tentacle or two in order to play the rest.

In homage to Alvin Lucier was a re-enactment of the American composer’s I am sitting in a room, in which a recording of an opening statement is folded back again and again into a series of recordings and re-recordings. After several iterations, the conversational fragments of this statement decay, and the audience is left with the compound feedback of the room’s variant frequencies. Lucier’s piece is intimately site-specific, relying on the nuances of each performance environment. It is possible that his work could also trigger a Zen-like total and utter annihilation of self, if not for the ‘get-up noise’ of scraping chairs, a few foldback yawns and the scratching of a reviewer’s pencil on paper.

Steve Reich’s Different Trains (1988) is evocative of the train journeys Reich made as a child, travelling between Los Angeles and New York visiting his estranged parents. Reich realised some years later that as a Jew, had he been living in Germany at the time, he would have been travelling on very different trains. The piece was originally performed by the Kronos Quartet. For the Sonic Space program, Reich’s piece was enacted with bittersweet aplomb by the South Australian based string ensemble, Aurora Strings. Different Trains is a minimalist ‘call and reply’ piece combining live performance, pre-recorded arrangements and sampled voice-overs. With great stage presence, the ensemble demonstrated a wonderful maturity of interaction with each other and with the pre-recorded compositions.

As Jon Drummond took to the stage to perform Sonic Construction 2, he had the delightful air of a guest conductor on The Curiosity Show. Coloured ink dropped into a clear vessel of water was relayed—using real time video—to software coded in Max, MSP and Jitter. The software interprets the motion and colour of the ink, triggering a sound event in a process based on the principles of granular synthesis. A sound ‘grain’ is the smallest (and therefore irreducible) particle of sound. The result is a drug-free and neurologically intact synaesthesia. Experiencing the seamless choreography of movement, colour and macro-sound in Drummond’s work lends itself to that phenomenal sensation of universal is-ness or, as a friend of mine once described it, that feeling you get when you sense the “thingy-ness of things.”

Street cinema

After a day of talks given by Drummond, Warren Burt and Robin Minard, Project 3 launched its Street Cinema program, exhibiting a selection of screen-based digital artworks over 9 successive evenings in Adelaide’s West End. The program included innovators such as Somaya Langley, Michael Yuen, Paul Brown, Warren Burt, Gordon Munro, Sonia Wilkie, Luke Harrald and Alex Carpenter, as well as James Geurts who received a commission to develop a work for Project 3. Enigmatically titled Gravitas, Guerts’ abstract video work is a painterly montage of what looks to be interference patterns from a psychic antenna, layered with thermal photographs of obscure figures and objects. The title is perhaps an intentional contrast to the nature of the piece which I read as being playful and conceptually unencumbered.

Perhaps less intentionally, several of the Street Cinema works within Project 3 bring the tenets and aesthetics of late abstract expressionism into the evolving realm of computational theory. Munro’s Evochord is a petri dish of genetic algorithms jostling to grow into something musical. Coloured points of light wriggle and swell to the discordant rise and fall of many singular notes. As if caught in a self-organising matrix, these lights collect briefly into homogenous groups of colour and sound to produce a sublime musical chord, before falling back into organised chaos.

Luke Harrald’s CONflict is a stunning synthesis of abstract sound and vision. On screen, delicate cathedrals of painterly light fade in and out to the bloom of a subtly shifting harmonic. Coded in MAX, the dynamic nature of this work is based upon the Prisoner’s Dilemma: a well-travelled model of logical probabilities used to explain the fundamentals of game theory. The screening of Monro and Harrald’s works feed directly from a computer as an application rather than being captured on DVD. This allows the process behind the development of the work to take effect: meaning that each time a viewer happens upon the piece it is unique, regenerated again and again from dynamic permutations of existing code. The difference between a static DVD recording and the use of a dynamic software application may be lost on the stroller who happens upon the work, watches for 10 seconds and moves on…but maybe not.

Innovation was evident in all the works, contemporary and historical, in Project 3, suggesting the capacity of artists and audiences to continually and mutually redefine relationships between consciousness and perception, art and nature.

Project 3, Contemporary and historical electronic arts, sound, video, installation and artist talks, artistic director Michael Yuen; Adelaide Festival of Arts, March 6-26

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 29