A conflict of interests

Rennie McDougall on criticism & its contradictions

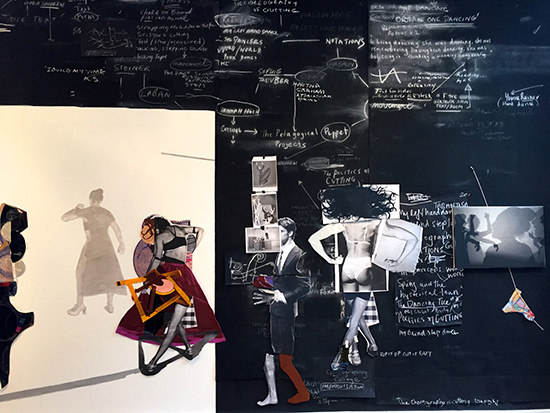

Image: Sally Smart, The Choreography of Cutting, 2015 (detail), installation view; Purdy Hicks Gallery, London

“So you want to be a critic? Isn’t there a conflict of interest?” Or so I’ve been asked, since starting to write.

This conflict of interest—between someone who dances and someone who thinks deeply about dance and writes about it—rings true as long as dancers are perceived as merely physical agents, incapable of deep scrutiny, and critics as crotchety outsiders.

Regardless, popular logic agrees: artists and critics are rivals. Criticism (reflection) is secondary, while art (experience) is primary. Certainly most criticism assumes a secondary position, directly responsive to someone else’s art. What about a criticism in which the primary subject is the critic, observing the critical mind in a Proustian way, whereby “the seeker is at the same time the dark region through which it must go seeking?”

…here Matthew Goulish in 39 Microlectures: In Proximity of Performance (2000): “If a critic believes in his or her own power to cause a change in audience thinking, that critic lives in delusion. Any changes of this kind are peripheral effects of a more central event. Criticism only consistently changes the critic—whether further narrowing the views of the art policeman, or incrementally expanding the horizons of the open-minded thinker. If we accept this severe limitation—that in fact the first function of criticism is to cause a change in the critic—then we may begin to act accordingly.”

Criticism at its most enthralling, is more like a thought process rendered than a judgement delivered. The critical mind arrives on the page structured, the order of words fixed, linear. This form is a necessary part of the translation: “to preserve the works of the mind against oblivion” (Coleridge and Valéry). The mind itself however abounds with contradictions, tangents, multiple voices, fog.

Thought process is action. Can writing be said to be in action? The mind wanders…

…to Roland Barthes in The Pleasure of the Text (1973): “[The text] produces, in me, the best pleasure if it manages to make itself heard indirectly; if, reading it, I am led to look up often, to listen to something else.”

…now Maggie Nelson in The Art of Cruelty (2011): “True moral complexity is rarely found in simple reversals. More often it is found by wading into the swamp, getting intimate with discomfort, and developing an appetite for nuance.”

I’ve never taken to the notion that ‘Opinions are like arseholes; everybody’s got one.’ Just because everyone has an arsehole, doesn’t mean the arsehole is not without its pleasures. Doesn’t everyone also have a face, eyes? Are those features rendered redundant because of our daily encounters with them? And, while everyone may be capable of having an opinion, not everyone is equal in the powers of articulation.

… now Oscar Wilde—flaunting his snobbishness ironically as much as taking himself seriously; an enviable skill—in The Critic as Artist (1891): “More difficult to do a thing than to talk about it? Not at all. That is a gross popular error. It is very much more difficult to talk about a thing than to do it.”

All this navel-gazing, this centring of the critic, may also arouse suspicions of snobbery, of self-indulgence. Remembering Goulish’s ideal of the critic as “incrementally expanding the horizons of the open-minded thinker,” I imagine such horizons calling for a vast outward-looking. That in locating myself as a site for change, what I actually reveal is not myself, but the world around me.

…now Eileen Myles in Inferno (A Poet’s Novel; 2010): “‘World’ always just means mind.”

…now David Riesman in The Lonely Crowd (1950): “…of course, one must always ask whether, in changing oneself, one is simply adapting to the world as it is without protest or criticism.”

If a critic becomes the site for change, they must also remain the agent of that change, not merely swaying to culture’s presumptive values. If the disdain for the critic is born of the art policeman’s narrow-mindedness, the adverse risk for the critic is to become so agreeable as to become insignificant, a yes-man. In this era of aggregated scores and Metacritics—of generalised tastes—the critic has an indispensable opportunity to speak for him/herself and dissent from popular opinion, whether by challenging what is routinely lauded or celebrating what is routinely dismissed.

…now Margaret Atwood in Negotiating with the Dead (2002): “There has been a widespread suspicion among writers… that there are two of him sharing the same body, with a hard-to-predict and difficult-to-pinpoint moment during which the one turns into the other… that one half does the living, the other half the writing. As for the artists who are also writers, they are doubles twice times over.”

How to observe the exact moment of writing? Thoughts are collected over time, sparked by conversations, art, unremembered sources. Tenuous connections are made, consciously, or congealing peripherally in such a way as to be indecipherable when looked at directly. Time is needed so that the mind might work its way towards self-comprehension without conscious interference; a picture slowly fading into focus. Ideas that seem self-evident easily fall apart when I try to explain to others. The mind completes one puzzle, then language must complete the same puzzle over again.

Now sitting at the computer: a flurry of typing, fragments of thought all pouring out, sometimes with words I don’t know that I know, this unknown double emerges, needing translation, a clearer phrase found, or a murkier one, another memory, another writer who said it better, cutting and pasting, new meanings created with each rearrangement; and then I read it back and it’s no longer simply my voice. Now the writing talks back to me.

…now Rebecca Hilton (Australian dancer, choreographer), a maverick when it comes to succinct insights about one’s dancing, telling me “You pick up movement very quickly. That means you don’t really have to do the labour of processing the co-ordination internally; it just arrives full-formed, like mimicry.” I’ve since imagined my self-hood as a collage of copied behaviours, borrowed ideas, influences. Which leads to an inescapably philosophical question: What is the essence of a person uninfluenced? Is there even such a thing?

A critic’s opinion is never wholly their own. Might criticism, once translated and expunged from the critic, who has drawn on a multitude of other voices, belong equally to the reader who resuscitates it in the reading, coerced into voicing the writer’s collected thoughts as their own, if only momentarily?

…again Wilde: “The only excuse for making a useless thing is that one admires it intensely. All art is quite useless.”

If all art is quite useless, let’s acknowledge the critic is also useless. That affords some freedom at least. No longer beholden to the burden of functionality (and hopefully not aspiring only to evaluative authority), criticism might now aspire to admiration in the same way the artist does; admiration requiring of the reader a critical mind—the very thing the critic is trying to advocate and cultivate.

…now an older woman, I forget her name, a self-proclaimed veteran of New York dance audiences, telling me “A choreographer has to make a decision. And really what they choose is arbitrary, but you have to pursue the decision so that it can lead you somewhere. And that is when things can get interesting, but still the decision is arbitrary.” I like how counterintuitive that sounds.

…now Connor, a friend, over dinner at my local Nepalese Indian restaurant, in whose company conversations like this are chewed over for hours. I repeat, “An artist has to propose something, they have to make a decision and follow through. And I have always had a conflict with that, the decision moment, the taking of perceived sides, even among the arbitrary.”

Connor says something about power always calling for resistance. (Connor is preoccupied with power, and usually steers the conversation this way.) Wherever authority is claimed, resistance to that authority makes itself known. To consider this conflict, between authority and dissent, within your own thought process, and to make that conflict visible, the doors of a privately-working mind flung open, exposed, in action, risking humiliation and judgement; now here is a celebration of criticism.

…now Keith Gallasch, who edited this piece, suggesting about my first-draft ending that “it does not allow the critic a body of work—surely the writing is a representation of an experience—the review translates one experience into another for the reader, and decisively.” To which I responded, “I will have another look. I think the final paragraph could be clearer, as to my interest in things being decisive without necessarily being wholly conclusive.”

Rennie McDougall

Rennie McDougall is a performer, choreographer and writer, originally from Melbourne, and now living and working in NYC. Rennie currently writes for RealTime and New York performance blog Culturebot. He is currently studying for a Masters of Journalism, Cultural Reporting and Criticism at the Arthur L Carter Journalism Institute at NYU.

Rennie and the Editors thank Sally Smart for allowing us to use an image of her installation The Choreography of Cutting. Rennie sees the image as corresponding to “the critical mind…in a state of movement.”

RealTime issue #134 Aug-Sept 2016