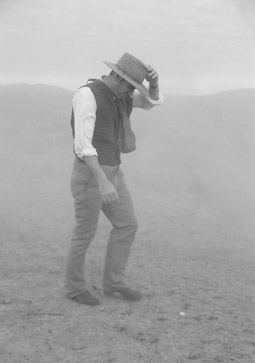

A (filmic) space between black & white

Jane Mills

Rachel Perkins, director One Night the Moon

photo Sam Oster

Rachel Perkins, director One Night the Moon

Looking round the Playhouse in Sydney’s Opera House complex, Kev Carmody rests his guitar and ironically mentions that when he’d last performed on Bennelong Point, he’d had to play outside in the forecourt. Next time, he promises, to loud cheers, he’ll be in the main theatre, where all the whitefellas get invited to perform.

With Paul Kelly and the entirely euphonious trio, Euphonia, Carmody was playing at Blak Screen/Blak Sounds, a 3-day festival celebrating the work of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers and musicians. Celebration was in the air, but politics were not forgotten: the event coincided with Reconciliation (formerly ‘Sorry’) Week.

Just as with Indigenous painting, there are signs that Aboriginal filmmaking is poised to challenge dominant, whitefella filmmaking, and take the artistic lead. Rachel Perkins’ new film, One Night The Moon, which premiered at this event, is a good example. Based on the true story of Aboriginal Tracker Riley in Dubbo during the 1930s, this extraordinarily powerful and startlingly original short film challenges many preconceptions about Indigenous cinema.

Paul Kelly, One Night The Moon

photo George Kanavas

Paul Kelly, One Night The Moon

Starring Paul Kelly as a white, racist farmer, it tells the story of a young, white girl (Memphis Kelly) who got lost in the outback and died due to her parents’ refusal to allow an Aboriginal tracker (Kelton Pell) on their land. With a boldness that catches the breath, Perkins has made a film whose originality lies in its operatic form, its refusal to obey the accepted rules of mainstream cinema concerning verisimilitude and realism, and its focus on the white family’s tragedy. Initially, the story was that of the black Tracker Riley but Perkins changed the focus to the white mother (Kaarin Fairfax). This disconcerts those in the audience who expect a black focus from an Arrente filmmaker. But, as Kelly says: “It is a story of knowledge offered and knowledge rejected, and the consequences that come from that, and that has great resonance for the history of both blacks and whites in this country.” And, as Perkins explains: “I wanted to make a film about the space between black and white Australians.”

Many of the films screened push boundaries in a variety of ways. None more so than those by Tracey Moffatt, whose landmark films—Nice Coloured Girls (1987), Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy (1990), Bedevil (1993)—challenge both societal and artistic conventions and, perhaps, helped create the pattern for the next generation of Aboriginal filmmakers. Not that Moffatt would necessarily agree that she has much in common with filmmakers who proclaim their Aboriginality. She sent a message from New York, where she now lives, saying she didn’t want to be known as an “Aboriginal artist.” While supporting her right to any label (or no label), it’s hard to see why she insists on the disclaimer. All her films screened—Lip (with Gary Hillberg, 1997), Heaven (1997) and Night Cries—display a strong political sensibility in which her Aboriginality, like her feminism, is impossible to ignore.

Night Cries, for example, weaves autobiographical material about the adoption of an Aboriginal child by a white family with a fantasy arising from the plot of Charles Chauvel’s film Jedda (1955). By proposing that Jedda didn’t die in the film’s last frames, but lived to become the middle-aged carer of her white adopting mother, Moffatt shows herself as preoccupied by issues of history, truth, survival and the need for radical change, as are many younger Aboriginal filmmakers.

There were several references to Jedda during the weekend. Darlene Johnson thinks “it’s an amazing film. In places the racism is so extreme that it’s almost laughable. But it also has a special place in our history. When it came out there was still apartheid in Australian cinemas: Aboriginals had to sit in different seats or couldn’t go to the cinema. But many Aborigines loved it. They saw Aboriginal people—stars—on the screen probably for the first time.” She also points to the huge amounts of documentary footage made by white colonialists in which Indigenous peoples had no involvement in their own representation; some of these images are used to powerful political effect in her film Stolen Generations (2000).

Johnson’s films cover a wide range of styles and subjects, from a mockumentary-style film about allergy (Dust Mite Be You, 2000), an award-winning short drama (Two Bob Mermaid 1996), to the heart-searing doco Stolen Generations (2000). But they all have one thing, at least, in common: “I guess they all have a ‘survival’ theme to them. Two Bob Mermaid, about a black girl who tries to “pass” as white, is very much about survival strategy. I wanted to explore that which is acknowledged and that which is disavowed: the conflicts and complexities of living in 2 worlds. Swimming is a metaphor for the need to negotiate these two worlds.” Criticised by some university students for representing Aborigines in a negative light—there’s a drunken female character—Johnson explains that she counters the stereotype by showing this character “as both a caring mother and someone who likes a good time and can get drunk—like anyone else.”

Erica Glynn is another whose films demonstrate a wide range of content and form. She describes My Bed, Your Bed (2000) as a comedy “that refused to idealise present day Aboriginal culture.” Her latest, Minymaku Way (2001), is a documentary about the work of the Ngangyatjarra, Pitjantjatjara, Yankuntjatjara Women’s Council in the remote desert communities of Central Australia. It shows the special malpa (working relationship) between some of the key anangu (Indigenous) women councillors and the white council co-ordinator. Once again, those who expect Indigenous filmmakers to focus on black culture to the exclusion of all white people, some of whom I spoke to during the weekend, criticise the film for its inclusion of a white voice and for its structure which reveals Indigenous community life to be complex. But the film gets its structure from the way in which the council itself works, not from the codes of conventional documentary filmmaking and as Erica reveals: “I don’t choose my films, they seem to choose me.”

The films of another potent filmic voice, Catriona McKenzie challenge preconceptions about Indigenous culture and filmmaking in very specific ways. Her 3 shorts—Box (1997), Road (2000), and Redfern Beach (2001)—have determinedly urban locations. They also attest to a wide knowledge and love of cinema from styles, genres and cinemas as diverse as Scorsese, Truffaut, social realism and magic realism.

Superficially, Ivan Sen’s films might appear to conform to the archetypal Aboriginal film. Journey (1998), Tears (1998) and Dust (2001) all represent Aboriginal teenagers living in outback or rural areas. But, ultimately, these impressive films by this assured, young filmmaker, whose love of the road movie resonates through almost every film he’s made, do not deliver the expected or the conventional. In her essay, “Well, I heard it on the radio and I saw it on the television…” (AFC, Sydney, 1993), Marcia Langton describes how myths of Aboriginality are created and perpetuated by filmmakers through the ways in which characters, typically, are de-conceptualised—socially, politically and historically. Sen’s characters all challenge colonialist representation by providing white Australia with a black history—one that shows how the 2 histories intersect or, importantly, fail to meet.

Glynn talks about contemporary life in terms of “juggling two worlds.” Johnson says something similar, discussing the need to negotiate identity and representation in 2 worlds: “I make films to educate my own people and white people about history—because both have been denied access to what really happened. We need to be exposed to our own history too. Many of our mob are just learning about it.” When making Stolen Generations, Johnson says she learned from meeting the 3 Aboriginal people stolen from their families as well as from a white nun who “did a 180 degree turn and now thinks what she did was wrong. I learned that her history is a part of white history too.”

To criticise Indigenous filmmakers for not making ‘typical blackfella’ movies, as some audiences both black and white do, is to ignore what interests many contemporary Indigenous filmmakers, what Rachel Perkins describes as “the space between black and white”, a space that some hope could be filled with a treaty.

On the second day of screenings, a white member of the audience asked, aggressively, why so few Aboriginals were present. Rhoda Roberts, the superb and tireless host, courteously pointed out that the films had already been seen by many, perhaps most, Aboriginals. She added that anyone who’d been at the opening night celebrations would realise how few revellers got to bed before 4am; attending a day of movies and music would be a hard call. As the films we saw attest, they have much to celebrate.

–

Blak Screen/Blak Sounds, part of Message Sticks program, The Playhouse, Sydney Opera House, June 1-3

For more Indigenous film see Alex Hutchinson’s review of shorts at FedFest & Teri Hoskin’s look at Kumarangk, a doco about Aboriginal women’s stories from Hindmarsh Island

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 17