A man of the people

Chris Kohn talks to the writer-director of the NYC Players

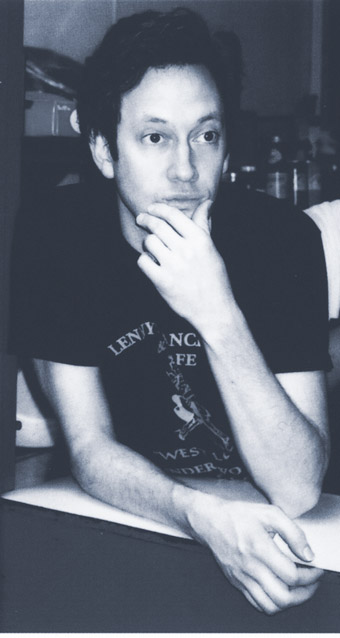

Richard Maxwell

photo Michael Schmelling

Richard Maxwell

Richard Maxwell has been making theatre in New York with his company, the New York City Players, for nearly a decade. He writes and directs all of his shows (except for a notable experiment with Shakespeare) as well as composing and recording the music. The productions share a stripped back, deliberately non-mimetic acting style (often labelled “deadpan” or “declamatory”) and explore the minutiae of social relations between everyday people, often in moments of personal crisis. There are shades of Raymond Carver and James Joyce in his writing—his worlds are populated by the unfulfilled and lost; ordinary types who seem powerless against the greater forces which rule their lives. The work is always tinged with loss, but is also optimistic.

I interviewed Maxwell in his office in Midtown. He had a small tent set up, taking up much of the small room, as he was about to head to Italy for a camping holiday. After giving some pretty useless wilderness tips, I asked him some questions about the shows he’s bringing to the Melbourne Festival (Good Samaritans, Showcase) and his thoughts on theatre making.

Your plays are often grounded in discussions about community, people in moments of crisis, the relationships between people and the world outside. Where do these characters and worlds emerge from?

I’ve noticed lately how influenced and susceptible I am to environments. If I pass by an environment on my bike, riding home at night, I see, I dunno, just the way something is lit, and it’s kind of something about peering into an interior from the outside. It really sets something off…maybe triggering some memory or something.

In the case of Good Samaritans, the setting of a rehab centre and the title conjure up notions of community service and altruism. What was the spark for this show? Did you want to explore particular themes or environments?

I saw some sort of rehabilitation centre, driving in the middle of nowhere, somewhere in rural Minnesota, and I started imagining what it was like and that leads to this exploration of helping; helping being a good thing, not helping being a bad thing. So you start thinking about good and bad, right and wrong, and start thinking about how they rely on each other, in order to exist; you sort of can’t have one without the other. And also I was thinking about an older couple and what a love story would look like between a couple of that age, because our culture is so…its influences are so mediated. Stories of love, particularly passionate Romeo and Juliet kind of stories, they are relegated to the teens.

You are well known for working with performers who have vastly different levels of expertise. In your new show, Good Samaritans, you have one actor who is trained and another who is not. How did that come about? Was it a deliberate choice?

It wasn’t deliberate. I saw plenty of people, both trained and not trained, it wasn’t designed to split it down the middle, that’s just how it came about. Although I think that it’s no surprise that it ended up that way, because I guess my feeling about it is it doesn’t matter to me how much experience you’ve had; if you’re right for the part, y’know, you’re right for the part.

What was the casting process? I imagine it may be different than if you are working with a cast of more equivalent experience.

We put an ad in this industrial rag, Backstage, which we’ve done in the past. Everyone I worked with in the building of the show I had worked with before, except for Rosemary [Allen]. She hadn’t had any real stage experience I guess, before this, but she’s a girlfriend of a friend of mine who’s in Showcase now. I knew Rosemary socially and the friend told me that she was taking acting classes. It’s a big part, so he was a little sceptical, you know, she’s a full time nurse, but I talked to her about it and she seemed, you know, really interested. My feeling is if people are into it, if they’re willing to commit what it takes to do something like that, that’s half the battle. I have a lot of patience for people if I know they are there with me, so the experience thing becomes kinda negligible.

When working with actors of different levels of experience, do you have to approach direction in different ways?

I work with people who don’t have any experience, I work with kids, I work with older people, and so it does have to change based on who the person is, and some people are more thoughtful, methodical, confrontational, people who need you to explain things, which I don’t mind at all. So it’s just a matter of finding out who and what these people are. I imagine it’s like teaching, you have to base your methods and your templates to every personality that you encounter.

As a director of your own writing, I imagine there must be a kind of internal artistic dialogue going on inside you. How does that manifest itself in the creation of a new work. Do you always bring a complete script to the process?

No, that’s the thing, when you start to know the people you are working with I start to think about the writing and whether it fits them or not. I tend to write for them, based on what I perceive in them, and sometimes I write against them, which is not to say that I am trying to sabotage them. Writing for someone can mean writing against them, sort of playing in the script with what would be expected.

Was Showcase written for Jim Fletcher?

Yeah. It was written with Jim in mind, but I didn’t know for sure that he’d be able to do it exactly. When I say I’m writing for people, I don’t think that I’ve ever looked at an actor I’ve worked with a number of times and said “wow, do I have a show for you.” It’s more like I see them in the part and whatever discrepancies might exist between what I am seeing the character to be and the actor to be I’ll change in the writing, rather than expect the actor to jump. It’s a really nice amalgam actually, in this realm of writing where it’s hard to separate where the person ends and where the character begins. I guess that can be very uncomfortable for people—I find that true with actors actually a lot.

You have created many shows in New York in the last 10 years and have developed a very distinctive aesthetic as a writer and director and as an important innovator in the Downtown theatre scene. In the last few years, touring internationally more, do you find different audiences come with different expectations or offer different responses?

I suppose. It’s hard to ignore or to not think about the fact that this inevitably will culminate in a live performance and, being an audience member myself, going to see other people’s stuff, I think a lot about the expectations that one brings to the theatre. But I imagine that most people coming to see something have seen something already and that if they haven’t then they’ve heard about what it is—“Oh he does that deadpan thing.” I can only imagine! (Laughs). Those thoughts, you can’t deny them, they go in there, I guess they influence things like everything else.

If you look at the title of my next show (The End of Reality), it’s evidence there of what people say, or what people have said and yet I struggle with that because I really try not to make something that is based on the audience being a block of one thing, a monolithic thing that comes and occupies the seats. And that’s kind of the basis for a lot of the fundamental ideas that I hold about performance—that it’s not a block, it’s many individuals and I’m happiest when there are a multitude of opinions and feelings happening at once based on who’s in the seats—it just feels more democratic that way. The less I determine what something means emotionally or psychologically for a character, the more the person in the audience is going to be able to project their own experience onto what they see.

Is that where some of your aesthetic comes from? The “deadpan thing” you refer to? Is it about allowing a more open range of readings?

To a lot of people my beliefs about character seem perverse, because I don’t want to talk about the pretend psychology of what the character is experiencing at all in rehearsal. I mean I have my own ideas, I have to write these characters, so I have my own ideas about them, but I don’t think it’s necessary to; sometimes it can interfere with the work of telling a story or putting on a play, when you have these conversations about what might this character be feeling. I’m much more interested in what, well, what you’re gonna be feeling in a situation where you’re up on stage with an audience or with someone else and an audience, y’know, and what that live environment will yield with everyone present. That’s the situation at hand and so let’s deal with that situation and not try to invent another one.

NYC Players, Showcase, Langham Hotel, Oct 12-16, Good Samaritans, CUB Malthouse, Oct 19-22, Melbourne International Arts Festival, www.melbournefestival.com.au

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 4