a place to give pause

virginia baxter: sylvie blocher, what is missing?, mca

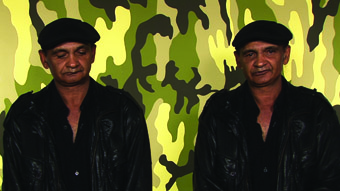

Urban Stories/Nanling-Guangzhou (still) 2005, Sylvie Blocher

courtesy the artist and Nosbaum & Reding Art Contemporain, Luxembourg © the artist

Urban Stories/Nanling-Guangzhou (still) 2005, Sylvie Blocher

RRIGHT NOW THE EPICENTRE OF THE SLOW ART MOVEMENT MIGHT JUST BE HOVERING OVER THE MCA. ON LEVEL THREE OLAFUR ELIASSON ASKS US TO TAKE (YOUR) TIME AND UP ON THE FOURTH FLOOR, WHERE WE GATHER FOR A MEDIA BRIEFING, FRENCH VIDEO ARTIST SYLVIE BLOCHER PASSIONATELY EXTOLS THE VIRTUES OF PAYING ATTENTION TO THE SUBJECTS OF HER VIDEO PORTRAITS; THE ENCOUNTER WITH ANOTHER IS A PLACE TO GIVE PAUSE.

The value of investing time to listen and watch is something Blocher knows well. In this exhibition, we see the results of many years of work on her “living pictures”, a series of individual video portrait projects each designed around a different kind of encounter. As a rule, she does not choose her subjects but either advertises or asks the gallery commissioning her to make the choice. Some subjects require a lot of time—seven hours in the case of one of her recruits for Ecstasy in which she invited 15 Indian men to enter a range of ecstatic states. In this case she did choose her subjects (though randomly, often in the street) as she was told that if she advertised she’d be swamped. As for how she elucidated the transcendent states on display, Blocher remains cryptic: “I created a space of freedom, without moral constraints, where everything was possible and experimental. It was long and difficult…”

Taking in the eight rooms that comprise the exhibition, you’re acutely aware of the artist’s ‘presence.’ Not that you see her, or hear the questions she calls her “tools that touch people” or her responses to the subjects’ answers. Instead you deduce what might be happening between the two in this other time-frame from what unfolds before you on the screen and in the eyes of the subjects that intriguingly suggest another space beyond it.

The images are projected at large scale as single or two-channel installations, the latter with little, if any, separation between the screens. In each case the relationship between the bodies on screen is slightly different. In the series entitled What is Missing? (2010) the subject (mostly in head and shoulders) speaks to us directly. As each speaks, a second embodiment of the same person appears as if silently watching or simply listening to the speaking self. Time and place are absent. There are dissolves to close-up, slight changes of angle—nothing tricky to interrupt the train of thought. The people are of varying ages and types and appear before a unifying backdrop (the American flag or wallpaper patterns of filigree or camouflage). Notably, all appear comfortable, even emboldened, before the camera. At the conclusion of each statement, the subject gazes silently outwards.

Living Pictures / Je et Nous (I and We)

© Sylvie Blocher

Living Pictures / Je et Nous (I and We)

Living Pictures / Je et Nous (I and We) “Imagine someone on the other side of the camera whom you will address in silence through your gaze,” Blocher told her subjects in I and We (2003, 55mins). One hundred residents from Beaudottes, one of the poorest towns in France were also asked to “write a sentence on solitude or beauty, topics we usually keep silent about and have the courage to be in front of the camera wearing a T-shirt with the sentence printed on it.” The result is a telling new take on the passing parade.

Among Blocher’s other collections are 10 self-made millionaires from Silicon Valley (Men in Gold, 2007, 36mins). These men, hand-picked by MOMA in San Francisco, are afforded more time and, again, Blocher’s technique allows us to see something else beyond their guarded revelations.

Living Pictures/What is Missing? (still) 2010, commissioned by Museum of Contempory Art, for C3West, Sylvie Blocher

image courtesy MCA and © the artist

Living Pictures/What is Missing? (still) 2010, commissioned by Museum of Contempory Art, for C3West, Sylvie Blocher

What Belongs to Them (2003, 36mins) features residents of New Orleans who signed up if they had something to say about slavery—economic and racial as well as psychological slavery. An African American man tells us about shooting a deer: waiting to identify its sex, aiming, how his bullet hit, how the animal fell. After he speaks, he is consumed by the pleasures of the hunt, of his prowess. As he tells us that the head of the buck now hangs on the wall of his garage, he is silent and looks out beyond the camera and we catch what might be regret or ambivalence or simply reflection on what he has just let slip to us and himself. The same uncertainty crosses the face of the millionaire as he wonders if his name engraved on a building or any trace of the possessions he has gathered will endure. “I hope so,” he says. “I hope the world is still here.”

In another room (Wo/Men in Uniform, 2007, 46mins), we meet members of the police force in Regina, the city with the highest crime rate in Canada. This time we see full bodies as well as close-ups.

“I work with the extreme complexity of bodies and my tools are not those used in journalism,” says Blocher. “My work consists of bringing to light an invisibility hidden behind social constructions and learnt conventions.” Here, as we might expect, the fixed faces leak fear: a rookie taking possession of her first revolver admits she practiced for a while in front of a mirror.

Perhaps most fascinating for the Australian audience is the material Blocher has gathered from a project in Penrith titled What Is Missing? (2010). “In the last four years, the MCA and Penrith Regional Gallery and the Lewers Bequest have worked closely with Blocher on C3 West: an innovative collaboration between artists, cultural institutions and businesses in Western Sydney” (MCA Media Release).

Here, Blocher says, “I began with the idea of what’s missing, which allowed me to use the popular form of a short video to highlight the internal conflicts between Penrith and the Panthers—the football club which since 1919 have shared their revenues with the community to help with health, education and culture but whose utopia is made shaky by the pressures to privatise their profits…I proposed to the Panthers that I bring their utopia up to date.”

The range of people who appear before the camera are as surprising as their revelations. Like the subjects of Andrew Urban’s gem of a TV series, Front Up (1995-2004), given time and patience, the taciturn Australian will express an eloquent depth of feeling.

An Aboriginal man tells the tragic story of his own and his brother’s forced removal and separation from their family. Contracting meningitis that led to his losing both sight and voice, the brother was permanently institutionalised. Now 50 years later the institution is to be sold for profit and the brother abandoned.

A teenager appearing in a t-shirt that reads “G F ck Y rs lf. Would you like to buy a vowel?” tentatively posits neo-Nazism as a way to deal with the growing populations of people who “should live like us,” while admitting, “Hatred is turning me into someone I don’t want to be.”

A middle-aged man makes a personal apology to Joern Utzon for the country’s lack of vision. A young girl has difficulty pronouncing “feminism” but gains strength as she declares, “What’s missing in Australia is a form of peace.” A Mexican immigrant would like to fight the absence of spirituality here by “learning how to speak to birds.”

Another fresh-faced boy is fearful of divisions in the community. Like many other interviewees in this series, to him the future appears bleak. He reports that fights will break out for no reason. “We are separating into groups that can’t communicate with each other, can’t even act with courtesy.” The only feelings he regrets are sadness and depression. “Tears are not necessary,” he says before quoting from A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “… For you in my respect are all the world: / Then how can it be said I am alone, / When all the world is here to look on me?”

In Urban Stories (2005, 9mins and 46mins) in a small room, we come a little closer to what might be Sylvie Blocher’s process in selectively capturing her shifting reflections on the self. On a visit to the Nanling Guangzhou Triennale, the artist meets a village woman in the street who had never seen a foreigner. “She started to talk to me, to touch my clothes and my hair. I asked her if I could film her. The next day I placed a camera in front of the studio’s sofa and let the woman use my body as a kind of tool…The woman touched me like a child, like a sister, like a lover, like a mother. It was like a rite of alterity. I stopped her after nine minutes. I couldn’t take any more.”

Sylvie Blocher distils the intensity of such encounters into absorbing private made public visions that richly reward the time and attention the viewer invests in looking and listening to retrieve all that is missing.

Sylvie Blocher: What is Missing, MCA, Sydney, Feb 17-April 26.

The exhibition is presented concurrently at Penrith Regional Gallery & Lewers Bequest, where it features work for the City of Penrith by Campement Urbain, a Paris-based collective headed by Blocher and architect/urban planner Francois Daune. The exhibition at Penrith Regional Gallery runs February 13-April 4.

Originally published in the March 1, 2010 online edition.

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. 43-45