a random revolution

urszula dawkins: cyberdada retrospective

CyberDada Retrospective, Troy Innocent, Dale Nason

photo courtesy the artist

CyberDada Retrospective, Troy Innocent, Dale Nason

“DIGITISE THE WORLD. (A NEW LIFE AWAITS YOU.)”—SO BEGINS TROY INNOCENT AND DALE NASON’S CYBERDADA MANIFESTO, WRITTEN AROUND 1990 AND REVIVED FOR A RETROSPECTIVE AT MELBOURNE’S NEW LOW GALLERY, CO-CURATED BY ACADEMIC AND CULTURAL CRITIC DARREN TOFTS.

“Live in CYBERSPACE where all feelings and physical realities can be psycho-chemically simulated. DON’T BE AFRAID: EXPOSE YOUR CIRCUITRY.” A couple of decades on, CyberDada seems both ‘old-school’ and prescient in its fierce embrace and ironic critique of the now-ubiquitous ‘digital age.’

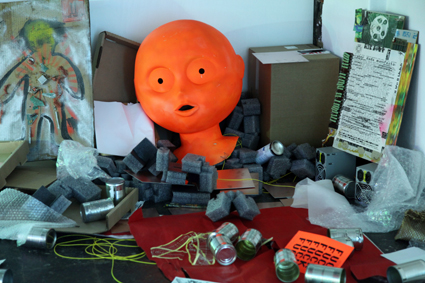

I hear it before I see it—the collective din of analogue synth sounds, a TR808 drum machine and several TV monitors pumping out copious white noise. Entering the basement space of New Low I’m confronted by accompanying visual noise—fast-cut videos projected onto walls, ‘sculptures’ made of techno-junk and a floor thick with label-less soup cans and scattered paper. CyberDada manifestos printed onto Lotto slips. Stencil cutouts, photocopied collages, and “FUCK” printed in pixellated type on old phone-book pages. A monitor lies on its side, camera taped to the front so that I see myself looking back at me.

Luckily there’s one explanatory panel amid the chaos: between 1989 and 1994, Innocent and Nason, then Swinburne Uni design students, took on the nascent digital media and cyber cultures in the heroic spirit of early-20th century forebears the Futurists and Dadaists. The result was their internationally-disseminated manifesto and a cache of events, films, performances and tactical actions that—along with the work of artists such as post-humanist Stelarc and cyber-feminists VNS Matrix–defined Australia’s emerging cyber-art scene.

This show is heavily ‘immersive’ without either video goggles or an Inter-Arts grant anywhere in sight. Its brash physicality and analogue aesthetic is completely overwhelming: works like the original CyberDada Manifesto video (1990) both jar and mesmerise with grainy graphics and endless rapid edits—half-pixel-based, half-hand-drawn images of what seem to be biological forms one second, circuit boards, newsreel fragments or broken test grids the next. Burgeoning patterns are abstracted by prototypical video effects, morphing into kaleidoscopic mandalas. An artificial iris becomes the only eye, an aperture through which a fractured, digitised reality is all that can be seen. Colour, endless editing and no time for interpretation, only visitation—a soup of images.

According to Troy Innocent, the historical moment of CyberDada’s birth held several contradictions. On the one hand, computers were seen purely as ‘tools’ in the design world; and on the other, incredible claims were being made elsewhere about the potential of new technologies to change the world. The concept of virtual reality was generating considerable hype; techno music inspired investigations into beat-induced trance states. But the creative capacities of computers remained relatively unexplored, mostly dormant since the ‘cybernetic art’ experiments of previous decades.

CyberDada, in part, took the piss—though, says Innocent, some people missed its satirical flavour. He recalls responses along the lines of, “YES, this IS the revolution, let’s replace the meat of our bodies and digitise everything!” Innocent and Nason made videos, playing with whatever effects and equipment they could get their hands on, commandeered dot matrix printers, devised performances and built installations out of already-obsolete techno-junk—creating a noisy, multi-form aesthetic that Innocent says was also influenced by the dystopian sci-fi aesthetics of Blade Runner and cyberpunk.

At the New Low show, embedded in and around the flashing images, fuzzed-out monitors and bits of motherboard is the other crucial element: language. The words of the CyberDada Manifesto are, like those of the Futurists and the Dadaists, bombastic, clever, premonitory, heroic, tongue-in-cheek, and ultimately seductive. “Hot wet nodes” meet “a perfect techno world.” “Pure brain to brain communication” is tempered by “virtual/smart drugs,” “muscles” and “mutation.”

As if the seizure-inducing videos around the walls aren’t enough, moving installation pieces cast sporadic shadows across the space, visually echoing the continuing single-beat rhythm of the TR808 and a near-toneless bass pulse. These taped-together assemblages of sundry manufactured parts, along with several of what Nason and Innocent describe as “Cybaroque totems” in the centre of the space have been newly created from materials kept in storage since the early 90s. Old projectors and laptops, polystyrene packaging, broken robot toys, multi-pin connectors, plastic tubing, circuitry, fake hair, string, wires, blinking LEDs, film canisters and pill bottles, glued and taped together, seemingly at random. “FUCK” appears here too, projected onto the ceiling.

CyberDada Retrospective, Troy Innocent, Dale Nason

photo courtesy the artist

CyberDada Retrospective, Troy Innocent, Dale Nason

Co-curator Darren Tofts describes Innocent and Nason as “fastidious archivists of CyberDada ephemera.” Mounting a CyberDada retrospective now is timely, he says, with the so-called ‘new aesthetic’ being touted as the intervention of the digital into the built environment. “CyberDada, as Lisa Gye has observed, were doing this more than 20 years ago,” he says.

“[Nason and Innocent] gave us the audiovisual style of the digital age before we even knew it was an age; and…much of what is described as the new aesthetic is CyberDada by another name. When posterity looks back on the digital age in a hundred years’ time, CyberDada will be remembered as its herald,” Tofts says.

The retrospective’s barrage of sound and image is unrelenting—a disorienting meditation that separates your senses from your brain. If originally CyberDada critiqued the hyped-up claims for a digitised future, its relevance is redoubled in the face of exponentially expanding consumer culture, with its endless media offensive and mounting detritus. In CyberDada excess is turned back on itself: it feels like walking into an aesthetic assault—it’s noisy, it’s ugly, it’s messy and you can’t even read a label on the wall to make sense of it. But at the same time it’s liberating—a weirdly entrancing brand of ‘fun.’ Where VNS Matrix devised a more streamlined, ideological ‘cyberart’ to ‘infiltrate the system,’ CyberDada aims instead for randomness; its very ‘unresolvedness’ ironically garnering its integrity. In this sense it seems less a precursor of the ‘new aesthetic’ than of contemporary live art—as a space where creative intervention is the generator of excitement and energy, a strategic rather than organised aesthetic.

CyberDada Retrospective, Troy Innocent, Dale Nason, New Low Gallery, Carlton, Melbourne, June 5-8

RealTime issue #110 Aug-Sept 2012 pg. 24