A remaking of resurrected manifestos

Andrew Fuhrman: Julian Rosefeldt, Manifesto

Cate Blanchett, Julian Rosefeldt: Manifesto

image courtesy ACMI

Cate Blanchett, Julian Rosefeldt: Manifesto

It’s a truism, but one worth repeating: not all literary forms are possible in all eras. Today, the manifesto is an impossible form. Of course, people do still write manifestos, just as people do still write mock epics in heroic couplets, but almost without exception these are failures.

Yes, the age of the magnificent screed has passed. And yet the great manifestos of yesteryear continue to fascinate, even if only as dazzling curiosities rather than roadmaps to revolution. We can still thrill to the wild surmise, the oracular speculation, of a Marinetti or a Malevich, a Picabia or a Breton, to the urgency and ecstasy, without believing that what art needs today is a new generation of polemicists.

German-born installation and video artist Julian Rosefeldt certainly seems free of any revolutionary pretentions. His new 13-channel work, Manifesto (2015), jointly commissioned by a half dozen institutions and festivals from Australia and Germany, takes a contemplative, somewhat ironic view of the art of the artist’s manifesto.

The work features none other than Cate Blanchett performing a series of brief composite manifestos in everyday contemporary situations. The texts have been patched together by Rosefeldt mostly but not exclusively from writings by artists associated with the avant-garde and the neo-avant-garde—the Dadaists, Futurists, Situationalists, Suprematists, Surrealists and all the rest.

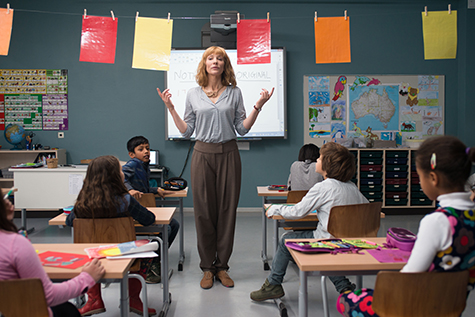

And so we have Blanchett as a primary school teacher and a choreographer, a newscaster and a eulogist at a funeral, a homeless man and a puppeteer. The idea, as explained by Rosefeldt, is to see how, if at all, these manifestos resonate with life in the 21st century.

On one screen, we find Blanchett playing a tattooed punk rocker in a crowded backstage band room. As the camera pans across tables littered with empty beer bottles and packets of crisps, she gives a hedonistic twist to the maxims of Vicente Huidobro and Manuel Maples Arce, exponents of Creacionismo and Stridentism respectively.

“Man is not a systematically balanced clockwork mechanism,” she sneers, while roadies in the background snort lines of coke.

On another screen, she plays an American financial analyst or trader in the employ of an enormous – and necessarily sinister—multinational corporation. Is there a connection between the Futurists who worshipped the glories of speed and today’s globalised financial markets? The possibilities tantalise.

On some screens the conjunction of text and scenario creates a charming and very watchable absurdity. On other screens the associations seem less productive. In at least one instance, where Blanchett plays a crane operator at an incinerator plant, a Müllbunker, the effect is unexpectedly poignant. Here Rosefeldt’s text is taken from a medley of architectural manifestos, including the wonderfully dithyrambic Daybreak by Bruno Taut, written in 1921, an example of manifesto writing at its most uplifting:

“How day will eventually break—who knows? But we can feel the morning. We are no longer moonstruck wanderers roaming dreamily in the pale light of history.”

Cate Blanchett, Julian Rosefeldt: Manifesto

image courtesy ACMI

Cate Blanchett, Julian Rosefeldt: Manifesto

And architecture is a favourite subject right through Manifesto. Although Blanchett adopts accents from America and the United Kingdom, on almost every screen there’s some fond tribute to a recognisable feature of Berlin’s built environment.

Manifesto was shot on a relatively tight budget over 12 days around Berlin in the winter of 2014. Given this difficult schedule, Blanchett has done remarkably well to transform these generic character types into sympathetic individuals. And she really seems to savour and enjoy the texts themselves, which, after all, were written for the mouth and for the ear.

But she is never unrecognisable. Even costumed as the homeless man, wandering the ruins of an abandoned fertiliser factory in East Germany with a beard and prosthetic nose, face smeared in ash, even there she is Cate Blanchett. And to be surrounded by this face, to see it territorialising every surface, creeping in its variations, is a fairly disconcerting experience.

The ACMI exhibition also features three other Rosefeldt works, including his miniature masterpiece Stunned Man (Trilogy of Failure, Part 2) (2004), a two-channel video installation in which a man simultaneously destroys and rebuilds his apartment. It’s a marvel of detail and craft.

And so is Manifesto. Every scene is meticulously composed. The camera lingers on crowded surfaces, trails slowly over bench tops and piles of interesting rubble. As you settle into the space, secret patterns emerge, verbal coincidences, parallel ideas, repeating visual themes.

As the primary school teacher, Blanchett implores her young pupils to remember what Jean-Luc Godard said: it doesn’t matter where you take if from, it’s where you take it to. The question, then, is where does Manifesto take its manifestos?

In spite of its technical strengths, its cinematic lustre, its cleverly coordinated sound design, the work is a bit sterile or academic. Or perhaps factitious is a better word: there are moments of joy and melancholy and eeriness, but you can hear the fluttering of an empty sleeve. Manifesto feels more like an intellectual exercise than an homage: like 13 moves in a glass bead game.

–

Julian Rosefeldt: Manifesto, multi-screen film installation, writer, director Julian Rosefeldt, performer Cate Blanchett; commissioned by ACMI in partnership with the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Hamburger Bahnhof-Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin and Sprengel Museum, Hannover; ACMI, Melbourne, to 13 March

RealTime issue #131 Feb-March 2016 pg. web