A small triumph

Sandy Cameron

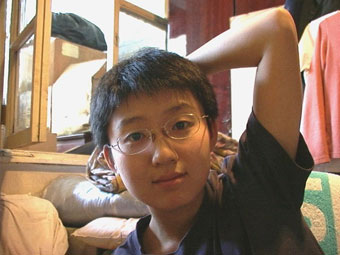

Liu Jiayin, Oxhide

In awarding Liu Jiayin the Asian DV Prize for her small masterpiece Oxhide (2004) at the 29th Hong Kong International Film Festival this year, the jury commended her for “demonstrating the new possibility of cinema, and radicalising the process of filmmaking.” While such hyperbole risks saddling the 23 year old director and her work with unrealistic expectations, Oxhide is the type of startling, refreshing film, at once experimental and familiar, that can revitalise the most jaded of viewers. Liu, a student of the Beijing Film Academy, is surely destined for larger stages than the theatre of the Hong Kong Science Museum lecture hall.

Oxhide captures the domestic squabbling of a small family (father, mother, daughter) in their cramped apartment as the family leather goods business endures recession. The narrative plays out in one location across just 23 shots on grainy digital video. From such stylistic minimalism and a seemingly banal narrative premise comes an engaging work that combines abstract formal composition with tender, humorous and honest domestic warmth.

Remarkably, Liu operated the camera, recorded sound, was production designer, edited and stars in the film. Her real mother and father play the parent characters. The resemblance to a home movie or any youthful amateurism ends there: the meticulous framing, staging and selection of conversational fragments reveals an astute cinematic mind. The shots are composed so as to give a disconcerting spatial perspective on the family flat; the family appear to have only a few square metres to live in. Lamps, leather materials and curios clutter the frame and obscure the protagonists, and the home is under-lit, completely masking room corners and silhouetting faces. It is interesting to note that each shot remains static, the immobility focusing the viewer’s attention on the intricate movement and staging.

Liu’s unusual camera angles sometimes focus on the cast’s midsections rather than faces, with off-screen dialogue and action more than enough to pique curiosity. A conversation seemingly about the significance of the heritage and style of scripting Chinese characters turns out to be, after a printer spits a flyer into frame, a chat about the layout of a brochure advertising a half price sale. The film is full of these revelatory moments, with humour often underpinning serious scenarios.

Indeed, such a contained, spare and personal piece is saved from being merely an exercise in low fidelity aesthetics by extensive use of irony, humour and affection for the characters. Despite the strained times through which the family lives, a genuine emotional warmth suffuses Liu’s non-figurative compositions. The film effectively taps into family dynamics as recognisable in suburban Australia as they are in provincial China. Liu, whose diminutive stature is a source of constant angst for her father, is plied with dairy products in an attempt to stretch her frame beyond the 5 foot mark. The eager patriarch then enforces his daily ritual of measuring her height against a doorframe. “If anything, you’re getting shorter!”, he wails at his full-grown daughter after one such check. There are some excellent dinner table scenes, in which the bickering family air their quotidian grievances. The exchanges are well observed, relating to the annoyances of loud noodle-slurping rather than any real aggressive tension. However, the family’s precarious financial situation is always in the foreground, as is the father’s obsession with saving face.

Oxhide draws immediate comparisons with the work of Abbas Kiarostami, in particular the recent Ten (2002) and Five (2003), and Liu cites the Iranian veteran as her primary influence. However, where a film like Ten has one straightforward camera set-up and Five no immediately tangible narrative thread, Oxhide manages to bring together the traditions of conceptual artwork with domestic drama and comedy.

Liu, like her hero, obviously enjoys blurring the line between documentary and fiction. While casting her family and articulating their financial difficulties and domestic squabbling may seem like a strand of neo-realism, this is offset by a visual style distancing the film from the kitchen-sink tradition. Liu pulls off the difficult trick of capturing the raw sentiment of neo-realism while still experimenting with a deliberately alienating visual style.

It seems that countries in the Asia region take it in turns to produce the world’s most challenging art cinema each year. 2005 switches the spotlight to mainland China, with the Chinese Renaissance and Asian DV programs at the Hong Kong International Film Festival offering a range of thought provoking, visually stunning works. While its grassroots, underground pedigree makes Oxhide not entirely representative of China’s recent output, it does focus attention on the innovative potential of the mainland’s new breed of filmmakers.

Oxhide, director/writer Liu Jiayin, People’s Republic of China, 2004

Oxhide was awarded the Asian DV Prize at the 29th Hong Kong International Film Festival, March 22-April 6.

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 pg. 22