Accepting the agency of the non-human

Jonathan W Marshall: Performance Studies International 2016

On Space Time Foam, Tomás Saraceno, 2015 installation

Performance Studies as a discipline was developed by director Richard Schechner and others out of the crucible of 1960s counter culture. Drawing upon anthropology, the study of ritual and political activism, its masthead The Drama Review was scrutinised by Australians, introducing many to Artaud, Grotowski, Fluxus, Kaprow, Cage, Cunningham, Hijikata, Barba, Kantor and more. Conceived as junctures for artforms, cultures and politics, performance studies institutions have waxed and waned. The University of Sydney’s Performance Studies department recently became Theatre and Performance Studies in a retreat from the formal impartiality long espoused by the discipline’s scholars.

While global in outlook, Performance Studies International has been held predominantly in the northern hemisphere. In 2015, PSI distributed the conference to multiple locations, describing it, with a touch of hyperbole, as “a year-long, globally dispersed and cross-cultural” performance of “UnKnowing.” This year, the conference was held in Australia, hosted by the University of Melbourne.

The challenge addressed by those who attended was nothing less than world climate change and the environment. Ironies abounded, much carbon being burnt to transport us to Melbourne. But then location and locally situated actions were espoused by many as entry points for political efficacy. Samoan poet and writer Albert Wendt’s formulation of the Pacific as an arc of oceanic interconnections between Polynesians and others might exemplify this coincidence of geopolitics and proud provincialism. However, the championing of ‘nomadic’ mobility and digital diasporas so prevalent in the 1990s recedes in the face of Brexit and the hyper-policing of Australia’s and Europe’s national borders.

New Materialism

At the heart of PSI 2016 was a slightly belated acknowledgement of the so-called New Materialism and its centrality to environmentalist alternatives. New Materialism reminds us that matter is never static. Atoms move, objects and systems interact. If we think of things, rocks, animals and systems as co-actors in the world—as subjects, capable of actively doing things; and the weather now is certainly ‘acting on’ us—then perhaps we might become sensitive to what Jane Bennett calls “vibrant matter” and “thing power” (Vibrant Matter: The Ecology of Things, Duke University 2010). Objects and weather systems perform as part of a complex dramaturgy within which we are interwoven, and to which we—like those made ghosts by the Fukushima tsunami—are all subject.

Bruno Latour

Bruno Latour

Bruno Latour, Professor at Sciences Po, Paris where he is director of Sciences Po médialab and a Centennial Professor in the Department of Sociology at the London School of Economics, is a founder of the New Materialism and his keynote placed him firmly at the centre of Performance Studies. He recently translated his book We Have Never Been Modern (1991) into Reset Modernity (ZKM, 2016), an exhibition which abounded with uncertain—one might say abject—artworks such as Pierre Huyghe’s Nymphéas Transplant (2014). This was a tank containing murky pond-water harvested from beneath the famous floating lilies of painter Claude Monet’s thoroughly sterilised garden.

Latour insists that art, science and politics must be messily collapsed into each other. Art remains a place to stage the impossible and hence a realm within which to grope towards apprehending anything which eludes our rational control or even our ability to think of it. Latour also cited Tomás Saraceno’s extraordinary installation On Space Time Foam (2015; see video), in which figures clambered awkwardly across fluctuating, clear film-enclosed packages of air located 24 metres above the audience. He noted that passing beneath the piece was terrifying, a reminder of the forces which the atmosphere exerts on us, and which we also influence, as illustrated by the movement of participants above as they pushed gases into fragile new shapes to be negotiated. In 2015, Latour staged a “theatre of negotiation” in Nanterre-Amandier, in which students were invited to participate in a virtual climate conference, lobbying on behalf of non-human assemblages such as swamps. Latour challenges us to experimentally act as if we are “objects,” without seeking to dominate; to be “objective” in thinking about our being and actions, but not in a Cartesian, Rationalist or Instrumentalist fashion.

_H110_x_W160_cm,_Inkjet_prints.jpg)

Antipodean Epic – Interloper, 2015, Jill Orr

Peta Tait

Peta Tait, Professor of Theatre and Drama at La Trobe University and a Visiting Professor at the University of Wollongong, extended this notion by proposing Jill Orr’s deliberately ridiculous but oddly moving Antipodean Epic (2015) as an example of performance that elicits a strangeness regarding one’s own subjectivity. Orr squats and cavorts birdlike in a wheat field at sunset, scrabbling in a mound of seed for a nest or perhaps food. Her comic and atypical movements embody, according to Tait, an emotional dysphoria which we cannot place, eliciting a destabilising empathy in audiences. Tait proposes that such aesthetic journeys beyond familiar human emotional expression unsettle our tendency to separate ourselves from the mise en scène we inhabit. We share performance networks with non-human actors.

My own contribution to the conference consisted of a call to move beyond thinking of “site-specific” performances and to identify sites—especially resonant and unknowable historical sites such as the Ring of Brodgar stone circle in far north Scotland—which themselves ‘perform,’ oscillating between filling us with a sense of their pregnant presence and rich history and then evaporating into the very absence of this history, now signified only by the tangible, haptic surfaces of turf and stone. Sites here not only provide stages, but also actors, who come and go as audiences move through their spaces.

Richard Frankland

Richard Frankland, Aboriginal singer/songwriter, author, filmmaker and Head of Curriculum and Programs at the Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development, interrupted such reveries by reminding delegates that when Indigenous Australians are asked to discuss climate change, or to share the sense that many have of their country as brimming with potent, tangible spiritual presences, most have more immediate social matters foremost in their minds. He offered an account of the Cultural Safety workshops he runs, dramatising in devastatingly simple terms the “cultural load” most Indigenous people carry, from the horrific regularity of funerals through to conflicts in negotiating land rights claims (who can make what claims on whose behalf), to the need to support and care for relatives and to deal with high levels of home invasions and assaults and interruptions to work and the financial stresses which arise from such unpredictable disturbances.

Frankland ran through three prerequisites for enabling Indigenous peoples to become the cultural leaders they should be, across all fields. Firstly, we need to move beyond viewing Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders as an “undifferentiated Other,” in the words of activist and historian Marcia Langton. Secondly, as historian Patrick Wolfe put it, colonisation is a process which continues beyond initial violence and the appropriation of lands. To put colonisation to rest one might begin with basic rituals honoring the dead. Thirdly, we must find a way to make home actually be “home” for displaced and harried Indigenous people.

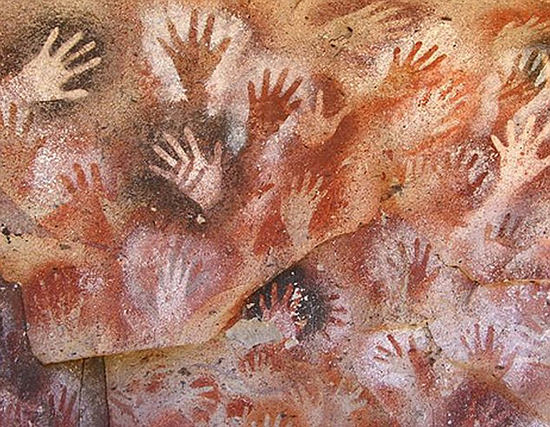

Handprints on the walls of Pech Merle’s caves, France

Rebecca Schneider

Rebecca Schneider, Professor of Theatre Arts and Performance Studies at Brown University, USA, too insisted on the racial implications involved in thinking about the environments within which we are embedded. She described imaginatively touching the ancient handprints emblazoned on the walls of Pech Merle in France (comparatively modern interventions compared with Australia’s, though coincident with the Brodgar stone circle). She identified their authors as hailing her. This gesture of greeting “inaugurates a relation” through call and response. It acts across distances of time between two subjects and generates distinction as palm is placed against stony palm. In touching the hand or the rock, we come to see that we stand apart from the other. Schneider claims that “performance is another word for the intervallic.” It acts across spaces between bodies or things, encouraging us to recognise alterity even as we empathise across it. The interval is the space of performance, which can be violent, as when US police execute black men for allegedly failing to respond to their hailing. Schneider nevertheless insists that because such calls act across distance, free exchange is possible.

From an environmental perspective, we must attend to these spaces of distance. The Pech Merle “performances,” and those of the modern woods above the caves, generate “cross-registers of time,” of things and events which act at different paces: mosquito time, rock time. Schneider argues that dramaturgical reflection enables us to encounter radical distinction. It is not only police who hail us, but protesters. On the streets, they call out “black lives matter” and by recognising such hailing we reconfigure relations between entities, groupings and populations.

Schneider’s model of performance is characterised by fissures at the fault-line of interaction. I am tempted to call it dialectical. It is based not only on immediacy, but also distance and reflection; on touching, as well as on drawing away. Schneider warns us that possibly uncritical celebrations of “liveness” and physical immediacy might be complicit with Capitalist exploitation. Capital also seeks to animate the world as ever moving, labouring bodies and productive systems. An intervallic pause might be what is required. Schneider’s keynote was a virtuosic rhetorical display, as much speculative poetry as academic analysis, providing a striking example of how metaphor might be deployed by artists and commentators to enchant and critique the world.

Watch Bruno Latour’s keynote lecture:

Performance Studies International 2016, No 22: Performance Climates. Keynote speakers: Bruno Latour (France), Peta Tait (Australia), Richard Frankland (Australia/Gunditjmara), Rebecca Schneider (USA). Conference convenor: Eddie Paterson & committee; University of Melbourne, Meat Market and Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall, 5-9 July

RealTime issue #134 Aug-Sept 2016