Activist art: origins and resurgence

Chris Reid: art & politics: exhibitions in Adelaide

Site Occupied, 2011, Cigdem Aydemir

digital print courtesy the artist

Site Occupied, 2011, Cigdem Aydemir

Much contemporary art involves pointed social commentary. Current concerns with racism, domestic violence, the erosion of democracy, the failure to prevent conflict justified on the pretext of religious difference and the challenge of climate change, preoccupy many artists as well as activists to an unprecedented degree. Three compelling exhibitions explore the varying approaches taken by artists to address such issues.

Giving Voice, Art of Dissent

This touring exhibition was initiated in 2014 by Hobart’s Salamanca Arts Centre to show how artists go beyond mainstream media to respond to significant political and social issues. Curator Yvonne Rees-Pagh has assembled a body of work created over several years in which artists address racism, asylum seekers, the environment and armed conflict.

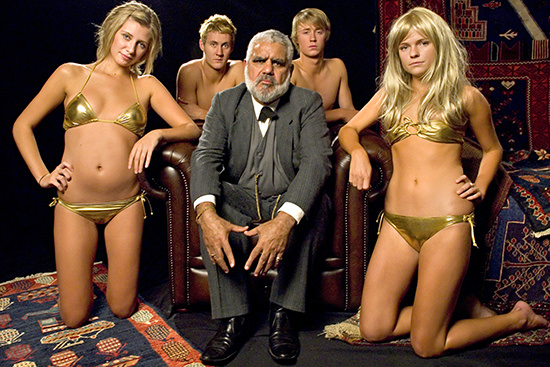

The exhibition includes some significant works that demonstrate Rees-Pagh’s theme. Richard Bell’s incisive and ironic 2008 video Scratch an Aussie probes white Australia’s psychological predisposition to racism by placing Indigenous people in the role of psychiatrists treating both themselves and privileged, white youth. Khaled Sabsabi’s video Guerrilla (2007), made in response to the 2006 Israeli invasion of southern Lebanon, is a quasi-documentary in which three unidentified speakers discuss their different strategies for dealing with the conflict.

Richard Bell, Scratch an Aussie

video still courtesy the artist and Flinders University Art Museum

Richard Bell, Scratch an Aussie

Cigdem Aydemir’s video Bombshell (2013) shows a woman’s black burqa swirling in the wind, recalling storm clouds and also ironically parodying Marilyn Monroe’s billowing dress in the film The Seven Year Itch. In Aydemir’s photograph Site Occupied (2011), a woman’s black niqab is enlarged to envelop a gallery space like a shroud to prevent entry. Both of Aydemir’s images reference restraints on women through control of their appearance.

Megan Keating’s The Ministry of Pulp and Smoke (2014) addresses the repudiation of the Tasmanian Forestry Agreement and its consequences for the environment using video imagery constructed from paper cut-outs. In Pat Hoffie’s drawings, Smoke and Mirrors (2012), storm clouds gather over sinking refugee boats.

James Barker’s Lest I forget (2014) is a confronting photographic triptych in a hinged, head-high frame showing images of sculptures of the stacked corpses of people killed in conflicts. The framing suggests a memento of deceased relatives. Locust Jones’ Everyday Atrocities (2008) is a drawing on a three-metre-long scroll resembling a giant stream-of-consciousness doodle. He redraws images of conflict shown in the news, thus distilling and aggregating key events to create an epic tale of unfolding, unending horror. Michael Reed’s many-faceted installation includes a pair of carpet runners, entitled Right, Might, Profit & Carpet Bombing/ Runners for Corridors of Power (2009) that bear texts such as “guns will make us powerful.” His work questions how anyone could work in armaments industries knowing the destruction they cause.

The artworks in this survey take a range of approaches from documentary video (Sabsabi) to expressionistic painting and drawing (Jones and Hoffie) to parody (Bell). Bell’s video Scratch an Aussie is unique here in offering an alternative position and a glimpse of a way forward by inverting stereotypical roles and directly challenging racist thinking. Former political adviser Pete Hay’s probing catalogue essay articulates the failure of democracy and suggests that recent social and technological developments require its renewal. He declares that “democracy will be refashioned from within the realms of dissent, if it is to be rescued at all.”

Night falls in the valley, Deborah Kelly

image courtesy Contemporary Art Society of SA

Night falls in the valley, Deborah Kelly

Planning for Tomorrow

Exhibited at the Contemporary Art Centre of SA, Planning for Tomorrow is also curated around the idea of the collapse of ideological and political systems that characterise recent decades. To explore this theme, curator Logan Macdonald has selected works by local and international artists and, in his persuasive introductory essay, discusses art theorist Boris Groys’ view of aestheticisation as an agent of change. The exhibition title is ironic, the principal message being that there is no such effective planning.

Viewers first encounter a selection of Damiano Bertoli’s posters of 2014-15 in which he has rendered texts by the 1960s Italian activist group Autonomia using the graphic design styles of Italy’s Memphis Group to create a postmodern blend of ideas that seems to trivialise both Autonomia’s calls to action and Memphis’s colourful and sometimes outlandish designs, suggesting that both movements were ephemeral. Cleverly counterpointing Bertoli’s posters is Deborah Kelly’s ironic take on unionist and activist banners, Night Falls in the Valley (2014), a huge version printed with the words “The billionaires united will never be defeated.”

Keg De Souza’s If There’s Something Strange in Your Neighbourhood… (2014), is a documentary video in which squatters, about to be evicted from a Yogyakarta district built over two cemeteries, talk about their experiences of ghosts and ghost removal—which becomes a metaphor for the squatters’ impending displacement. De Souza’s camera shows each interviewee reflected in a mirror rather than facing us directly—superstitions about mirror images imply that the speakers are already ghosts. The mirrors used in the video are separately displayed in the exhibition, inviting viewers too to look for ghosts.

Destroyed World, Santiago Sierra, Planning for Tomorrow

split-screen video still courtesy Contemporary Art Society of SA

Destroyed World, Santiago Sierra, Planning for Tomorrow

The central element in Planning for Tomorrow is Santiago Sierra’s video Destroyed Word (2010), a split-screen image of 10 elements, each showing one letter of the word KAPITALISM in monumental physical form being systematically destroyed by labourers. The letter K, constructed from brush fencing, is incinerated; P is timber systematically sawn into pieces; and M concrete, demolished like a building. Here, Sierra employs ‘proletarian’ labour to symbolically destroy the ideology that oppresses labour.

Macdonald’s exhibition demonstrates a variety of formal, conceptual and strategic approaches to activist art within an overall theme of the failure of government. Bertoli’s reference to the Autonomia movement in 1970s Italy begs us to consider the effectiveness of more recent movements, such as Occupy. De Souza involves a community in her video production, potentially sensitising that community and positioning it as an opposition and making us aware of its cultural traditions which may soon be lost. By contrast, Sierra’s artwork frequently involves paid labourers undertaking demeaning activity. Implicitly positioning himself as entrepreneur and overseer, he both enacts and critiques the capital-labour power structure.

The generation of an aesthetic response to human-induced crises is central to both Planning for Tomorrow and Giving Voice. In confronting us with the issues that preoccupy these artists, the curators provide insightful meta-narratives on the nature of activist, political art. They introduce us to artists who, to a greater or lesser degree, are themselves political activists. Art is now often seen as an alternative mouthpiece to the political left, filling a vacuum in post-socialist dialogue, and we’re reminded that the right to express dissent is hard-won.

The Photographs Story, 2004-16, 3 channel video and sound installation, Peter Kennedy

video still courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane

The Photographs Story, 2004-16, 3 channel video and sound installation, Peter Kennedy

Resistance: Peter Kennedy

At the Australian Experimental Art Foundation is a survey of Peter Kennedy’s pioneering video work since 1971. In the 1970s, video was a new medium that defied traditional commodity art-forms and enabled exploration of wider subject matter and the inclusion of sound. Kennedy was not only a pioneer of video as a medium but of politically and socially engaged art, concerned with the way in which communications media structure our perception. This landmark exhibition includes Kennedy’s video Introductions (1974-1976), a record of his initiation of interaction between four diverse social clubs—an embroiderers’ guild, a bushwalking club, a hot rod club and a marching girls club. Bringing them together emphasised women’s art in the burgeoning feminist era, raised environmental issues and challenged gender-based social barriers. In working outside the gallery to connect communities engaged in cultural activities, Kennedy prefigured work that would today be described as relational art.

Resistance: Peter Kennedy also includes the artist’s On Sacred Ground (1983-84) concerning Aboriginal land rights and self-determination, and November Eleven (1979), a collaborative work analysing the dismissal of the Whitlam Government in 1975. Also included is a new work, The Photographs Story (2004-16), involving Kennedy, his wife and son as subjects in a moving response to media coverage of the apparent death of a small boy caught in crossfire in Palestine in 2000.

Exhibition curator Matthew Perkins notes in his catalogue essay that “Socially engaged practices have returned to the contemporary art agenda with great force in recent years, encouraging a critical reflection of avant-garde practices that emerged from the counter-culture period of the late 1960s.” In his talk at the exhibition opening, Kennedy made clear that aesthetics and politics are closely intertwined, as his work over 45 years amply demonstrates. Peter Kennedy’s ground-breaking approach to the forms, the subject matter and the role of art helped set the stage for the kinds of work we now see in exhibitions such as Giving Voice and Planning for Tomorrow.

Viewers looking at activist art simultaneously occupy two positions: as engaged citizens, potentially encouraged by the artwork to protest, and as a detached audience, appreciating the work as art. While placing activist art in a gallery has been seen to commodify and neutralise it, such art has the potential to provoke viewers into deeper thought and possible action, and to sow seeds in the wider community. The art in these exhibitions is a crucial component of the continuum between artistic apprehension and activity on one hand and collective, public action on the other.

–

Planning for Tomorrow, Contemporary Art Centre of SA, 9 April-15 May; Giving Voice: The Art of Dissent, Flinders University Art Museum, 23 April-26 June; Resistance: Peter Kennedy, Australian Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide, 3 June-9 July

RealTime issue #133 June-July 2016