Activists' Argentina

Dan Edwards

The Take

photo Andres D’Elia

The Take

Towards the end of The Take, one of the filmmakers, the writer Naomi Klein, tells the story of a stranger who approached her at a railway station shortly after her arrival in Buenos Aires. He handed her a letter warning: “Don’t be what we have become. We are the mistake that is your future.” The Take is the story of a group of Argentinians striving to reclaim their work, their lives and their future from the ‘mistake’ that in 2001 laid waste their economy.

Argentina enjoyed a burst of unprecedented economic growth and prosperity under the ultra-liberal economic policies of the Menem government of the 1990s, which saw the privatisation of everything from public utilities to street signs. But in 2001 the bubble burst, the currency collapsed, and with no market regulations left the foreign capital that had flooded the country for a decade was withdrawn overnight. As we see in an extraordinary sequence of The Take, the banks’ reserves of capital were literally trucked out of Buenos Aires in the dead of night in armoured vehicles under the protection of police escorts. Argentinians awoke to find the banks bolted and their life savings gone. The country was declared bankrupt in the biggest debt default in history.

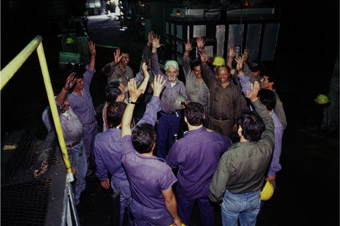

In the aftermath of the economic collapse, Argentinian workers began taking matters into their own hands, occupying abandoned factories and setting the production lines in motion, running the enterprises on a co-operative basis. The first of these co-operatives was the Zanón Ceramics Factory, expropriated in October 2001, followed by the Brukman Garments Factory 2 months later. Intrigued by the stories emerging from Argentina, Canadians Avi Lewis and Naomi Klein set out to document the formation of one of these worker-controlled businesses. Inspired by the Zanón model, former employees of the Forja Auto Parts Factory occupied their plant and embarked on a long struggle to transform the moribund factory into a working concern.

As The Take progresses, we come to identify strongly with the workers’ cause, embodied by Freddy who leads the attempt to form the Forja Factory co-operative. We see Freddy with his cute children, his attractive wife and his sympathetic, hard-working colleagues. In contrast, the Forja Factory owner and Argentina’s politicians are construed as duplicitous, self-serving and untrustworthy. The Take’s politics are hardly subtle, but the film is saved from being straightforward agit-prop by the filmmakers’ reflective positioning in the story. They make no bones about their sympathy for the co-operative movement, and Klein explains in voice-over that she and Lewis were drawn to Argentina in the hope of finding a functioning social and economic model that might serve as an inspiration for the movement against corporate-driven globalisation. Once in Buenos Aires, video cameras in hand, they join the front line of the workers’ fight, sitting in on meetings, visiting workers’ homes and at one point getting tear-gassed by police. The filmmakers are participating witnesses in these events and we see Freddy and his colleagues forge a relationship with Lewis and Klein as the story progresses.

Irrespective of the filmmakers’ politics, the Argentinian experience is a stark illustration of just how anti-human and fundamentally irrational unfettered laissez-faire capitalism can be. It’s no news to anyone that police are frequently employed to suppress labour movements and keep workers working, but in The Take we see the opposite scenario unfolding. During the struggle to get the Forja Factory going, the Brukman Garment Factory is surrounded by police mobilised to keep the factory idle and the workers unemployed. It’s a bizarre moment, given the co-operative has been running the abandoned factory as a profitable enterprise, but the action makes clear what is at stake here; Argentina is in the midst of a battle over the kind of capitalism that will be tolerated in today’s world. The co-operatives are based on local trading, grassroots democratic decision making and localised collective ownership. This is a mode of participatory capitalism that places capital at the service of our psychological and material needs, in contrast to the model endorsed by the IMF which allows economic elites to flit capital around the world at will while being completely insulated from the consequences.

The Take is a stirring and emotionally engrossing work, and a confronting portrayal of the misery ultra-liberal economic policies can generate. The film’s major weakness is a lack of historical perspective, particularly evident in the potted history of Argentina offered early in the piece. But where other recent leftist political documentaries like Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 and Robert Greenwald’s Outfoxed offer critiques of our media saturated, corporate-controlled world, The Take provides a refreshingly positive portrait of ordinary people attempting to forge an alternative form of social organisation. It remains to be seen how far the cooperative movement can be taken, but in the meantime The Take is an inspiring testament to people’s preparedness to lay their future on the line in the struggle for a more equitable and genuinely democratic world.

The Take, producers Avi Lewis, Naomi Klein, director Avi Lewis, writer Naomi Klein, www.nfb.ca/webextension/thetake

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 21