Adelaide Festival 2004: First Night

Keith Gallasch

Forced Entertainment

Royalty Theatre, March 1-12

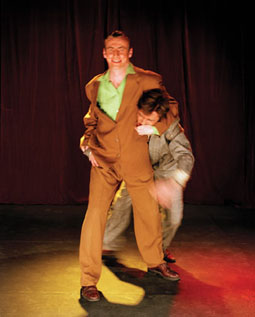

Richard Lowdon, Robin Arthur, Forced Entertainment

photo Hugo Glendinning

Richard Lowdon, Robin Arthur, Forced Entertainment

In the Adelaide Festival’s long history of programming remarkable and often provocative works taking on the challenges of form and the politics of performance, Forced Entertainment is in there with the best.

This is nightmare theatre. It realises the worst fears of performers (and audience) on the stage of a first night performance. Wracking nervousness, hestitancy, forgetting, being abandoned and going too far all fester and erupt amidst perverse versions of formulaic routines that have long lost their meaning. Performer fear and hostility is masked for the 2 hour duration with faces perpetually locked into steely grins and voices into rigid good manneredness regardless of the anger and anxiety issuing from between clenched teeth. From this taut physical framework, an appalling state of being, Forced Entertainment wrench a world of meaning. And it’s a peculiarly British world with its thin veneer of obligatory good behaviour and its evocation of an exhausted theatre tradition of music hall and beachside entertainment (appropriately presented in Adelaide’s tacky old Royalty Theatre), suggesting the limits this culture has reached. British television comedies and detective dramas display some of the same astonishing hostility and paranoia, but not at this surreal level and are nowhere near as testing of their audience.

The performers reassure us that all is well, that we will not be disturbed, that there will be no smells, no blood, no erections…and the list goes on and on escalating with possibilities alarming and banal until you feel like you’ve actually been submitted to all these horrors or, fascinatingly, that you encounter very few of them on your average night out at the theatre. You also realise pretty soon that you are trapped in a litany-based show and that every very long list will be followed by another or a set of repeated actions that will initially interest and then bore and then become curiously fascinating as you sink into the reverie groove and the sheer poetry of bitterness, fear and loathing acquires a patina of unseemly beauty.

The reassurances are empty gestures. The blindfolded company point into the audience, uttering horrifying predictions of car crashes, cancers and ruined relationships: “I’m getting something….she doesn’t blame you entirely.” The routines are bland (a woman perfunctorily explodes the balloons she is dressed in with a cigarette), surreal (an utterly unslick card trick routine has performers brutally stuffing cards into mouths and down trousers) and panicky to the point of existential crisis. Not only can the comic not recall punch-lines, he can’t even get the set-up right and lurches from one faulty joke scenario to ever more appalling and obscene ones, as if having no belief in what he does or tells, flailing about with a saw in his hand (as if from some other routine he’s forgotten), until he cries out for his fellow performers to save him. “I’m scared now. I’m dead now.” The upshot is that a female performer immediately apologises for the comic’s “indulgent” performance. True to the evening’s form, she overdoes it and has to be hauled off stage, kicking and screaming, shaking off her captors behind a curtain, crawling back on stage, ever repeating her histrionic apologies to be dragged off again in a rancorous dance of frustration.

As the night unfolds routines return with added intensity. Early reassurances are replaced with requests to “try to forget about cars, cigarettes…sperm, blood, shit on the sheets…really good blow jobs…refugees in shipping containers…” and more and more. The blindfolded seers return assigning horrible fates (including “refugees in your living room”), eliminating many of the audience as they point wildly around the theatre and we squirm in our seats.

The pressure on the audience increases painfully with a barrage of thank yous along with “you were super” and “give yourselves a round of applause,” escalating into telling us we were “politically spotless”, “not racist”, “not the kind of men in suits who go home and beat up their wives” and, greeted with applause and laughter: “You stayed.” However, the mood changes alarmingly, initiated by the female performers. We are told we stink, that we are losers and worse. The men are embarassed and apologetic but their interjections are greeted with the bluntest statement of the night, a loud and repeated “Shut up!”, abrasive, shocking even in these horrendous circumstances.

The comic with the saw enters blindfolded, flailing about, asking us, begging us to forget all about this night. Elsewhere on stage the ‘dummy’ from a comic duo has been tucked into a plastic carry bag by his partner, zipped up and left onstage, only his head in view. Fearing the saw, the man in the bag inches agonisingly away, tips, landing on his forehead, rests there, falls sideways, struggles up…For a moment it looks like something very real and very ugly might happen. But it’s only theatre.

First Night is one of the most thorough demolitions of the theatre-going experience I’ve witnessed, a satisfying totality, rigorously framed and performed with a courageous and brutal consistency. Without any of the usual character mechanisms the performers create a believable team of theatrical delinquents and misfits, bizarrely puppet-like with their fixed demeanours , limited gestures and list-speak. Without a plot they still induce pity, fear and even, for some, catharsis. This is wonderful ensemble playing borne of a 20-year company history, pushing to the limit even the most affectionate fans of contemporary performance, testing the contract between performer and audience and giving pause for reflection on what the theatre gives us and what it neglects, fears and avoids.

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 27