adjusting to the artificial others

kirsty darlaston: the uncanny valley

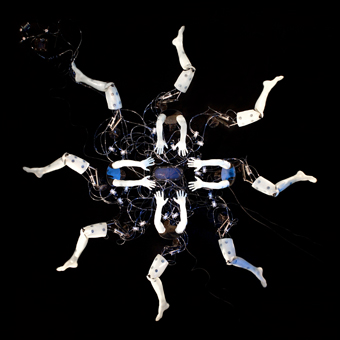

Living in Sim, Justine Cooper

image courtesy of the artist

Living in Sim, Justine Cooper

THE UNCANNY VALLEY TAKES ITS NAME FROM A GRAPH DEVELOPED BY JAPANESE ROBOTICIST MASAHIRO MORI IN 1970 TO MEASURE THE EMOTIONAL RESPONSES OF HUMANS TO THE DEGREE OF ANTHROPOMORPHISM IN ROBOTS. THE ‘UNCANNY VALLEY’ IS A PRONOUNCED DIP IN THE GRAPH WHICH OCCURS WHEN PEOPLE REACT NEGATIVELY TO THE ROBOTS BECOMING CLOSER TO THEM IN HUMAN APPEARANCE. THIS VALLEY IS WHERE THINGS SEEM HUMAN AND NOT QUITE HUMAN AT THE SAME TIME. TO QUOTE CURATOR LYNNE SANDERSON’S CATALOGUE ESSAY: “THIS IS THE PLACE WHERE ZOMBIES AND CORPSES THRIVE. IT IS ALSO WHERE MANNEQUINS LIVE…” LIKE MORI’S EXPERIMENTS THE EXHIBITION PRODUCES A RANGE OF CONTRADICTORY REACTIONS.

On the opening night we all crowd onto the viewing platform in a small side room waiting for Peter William Holden’s Arabesque to fire up again; it takes about 12 minutes for the hydraulic system to reset itself. Finally, the opening bars of Strauss’ Blue Danube can be heard and the performance literally kicks off. Eight robotic legs and arms move in time to the entire piece of music, and I hear someone mutter behind me that it is a fitting tribute to such a trite piece of music. Perhaps he means we’ve heard it so often that it has entered into the realm of artifice.

Arabesque, Peter William Holden

image by Medial Mirage/Matthias Moller

Arabesque, Peter William Holden

The photos of Arabesque in the catalogue show glowing iridescent legs and arms; a slow shutter speed must have been used, as luminous lines of movement are visible as well. These photographs of the “mechanical flower” are quite beautiful, whereas the artwork itself is fascinating in a different way, mainly with how it works. The cast arms and legs are made from a translucent material which has the appearance of waxy, dead skin. They are powered by hydraulics, with air periodically hissing its release, accompanied by the click of the limbs as they move. The artist deliberately left the many cables and workings of the sculpture in sight, acting as a kind of puzzle as to how it operates. People standing next to me laugh and clap and cry out “brilliant.” When taken in the context of the Uncanny Valley thesis, this seems akin to laughing at a funeral—that tendency to laugh in moments when not quite comfortable. I overhear many other people saying “It is like a…” which seems to signify that the work has entered the realm of the uncanny—as something for which we don’t yet have a language.

Dominating the gallery space is Justine Cooper’s photographic and video work Living in Sim which Cooper made as an outcome of her residency in at the Centre for Medical Simulation in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Presented in multiple formats, DVD, photographs and online, the work employs medical mannequins used to simulate patients for the training of medical practitioners. Cooper presents us with a hyper-real medical centre, complete with mannequins of aged care patients in wheelchairs, imposing hospital directors and the heaving breasts of nurses. One gallery wall is covered with small photographic canvases; nearly all of the dummies pictured on these have their mouths open as in silent screams, or maybe they are singing? In this hospital drama there is no blood, dirt or overcrowding; everyone who needs a bed has one, including Noctomum who has just given birth to nine children from multiple races. Another wall features images that Cooper has taken of actual simulated medical training exercises and these are quite affecting, particularly the mournful photograph of wheelchair-bound patients stuck in the corner and seemingly neglected.

The gallery space is also dominated by the sickly sweet soundtrack of Cooper’s video work. The DVD features blood, orifices and mess. The soundtrack croons on about the intimacy of doctor-patient relationships. The patients and medical staff of this “community living out the drama of health care” are further realised through a blog (livinginsim.com) which features posts and poems by the fictional staff members and video and photographs of their world. The mannequins use the blog to debate issues, such as plastic surgery (which Nurse Smilodon is vehemently against) and artificial insemination. The blog is what makes this artwork paradoxically ‘come to life,’ a demonstration of Cooper’s astute observations on the artificiality of online communication. The staff’s blog posts and biographies bring the comedic element of the work into play along, with more disturbing elements. In the visitors book in the gallery some visitors have written that the exhibition is offensive, stupid and pointless, asking that old question ‘is this art?’ One contributor has aptly written: “Disturbing? I find episodes of Master Chef more disturbing! I think some people in our health system must feel like dummies!”

The other two artworks in the exhibition are somewhat dwarfed, both in terms of size and complexity. David Archer’s A Journey Into the Mind takes us back to the Victorian era when experiments with robotics and automata were just appearing—the toys of the upper classes and the amusement parks of the masses. This sculpture is a hand-painted arcade style machine where the viewer looks into the lens and turns a handle. The human head inside the machine slowly opens to reveal a skull, which also opens in turn, revealing a peanut in the place of a brain. The simple mechanism and ‘message’ of this work is a reminder of how far science has come in robotics and yet how little has been achieved. Rona Pondick’s Jawbreakers is also a simple work, a jar of brightly coloured lollies stands on a shelf. On closer inspection these jawbreakers are revealed to be made from toothy cast jaws. Pondick writes that she sometimes wants to bite people she gets angry with, but has to stop herself because it’s socially unacceptable. The piece spirals in on itself—you bite a jawbreaker, it bites you back. These are lollies that will break your jaw and are broken jaws. It is a simple, playful piece. Pondick has used maniacally grinning teeth in her work previously; these little disembodied mouths can be quite disturbing, even uncanny.

With its dark humour, Uncanny Valley rides the fine line between comedy and drama and is at once disturbing and questioning. The exhibition functions in a very visceral manner with its small stories of real and artificial life in a darkened room. But the artificiality of the materials and media don’t quite allow for interaction with our own soft, warm bodies; somehow we feel excluded—surely part of the fear that fills the dark spaces of Masahiro Mori’s ‘uncanny valley.’

The Uncanny Valley: An exhibition exploring the not quite human, curator Lynne Sanderson, RiAus, Science Exchange, Adelaide, June 4-July 23, www.riaus.org.au

RealTime issue #98 Aug-Sept 2010 pg. 36