an audience of your making

john bailey: big hart, kage, the rabble, aphids

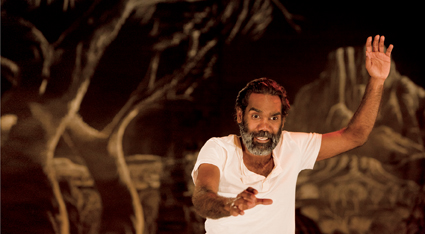

Trevor Jamieson, Namatjira

photo Brett Boardman

Trevor Jamieson, Namatjira

OF ALL THE AXIOMS BY WHICH WE EVALUATE A WORK OF LIVE PERFORMANCE, ITS SUCCESS IN MEETING ITS AUDIENCE SEEMS RELATIVELY IGNORED. I DON’T SIMPLY MEAN THE RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN A WORK AND THE BODIES AND MINDS OF THOSE WHO WITNESS IT—THERE’S NO LACK OF DISCUSSION AROUND THE FOURTH WALL, IMMERSIVE THEATRE AND THE LIKE. BUT WHEN IT COMES TO THINKING THROUGH WHO IS ATTRACTED TO A PARTICULAR WORK AND WHY, IT WOULD SEEM A MATTER OF MARKETING RATHER THAN AESTHETICS. IT’S FOR THIS REASON THAT TOO MANY THEATRE-MAKERS, WHEN ASKED ABOUT THE ASSUMED AUDIENCE OF THEIR EFFORTS, CAN REPLY ‘EVERYONE’. WHICH TOO OFTEN AMOUNTS TO ‘NO-ONE.’

Four recent productions to grace Melbourne suggested more nuanced and considered answers, playing on audience expectation and knowledge and seeming to understand that a work that will appeal to a universal audience is as unlikely as the existence of a universal human. I’ve never come across an instance of art that hasn’t found its detractors; to acknowledge this is a primary step for artists, and to proceed anyway an act of essential, necessary bravery.

big hart, namatjira

Big hART’s Namatjira takes a bold stance in this regard. The work is an exploration of Australia’s most famous Indigenous painter, Albert Namatjira, whose art was among the first to gain widespread recognition in white Australia from the 1940s onwards. But far more than straightforward biography, Big hART incorporates a mode of direct audience address that denies its viewer the opportunity to experience the work as if through a one-way mirror. From the outset performer Trevor Jamieson speaks to his audience, but not just any audience: Namatjira assumes that its audience is white.

As a work with a heavy touring schedule, I can’t tell how this gambit would travel, but in the inner-city surrounds of the Malthouse it seemed disarmingly appropriate. Jamieson jokes about progressive white Australians who might want to give their children Aboriginal names, and wonders whether a service should be established to advise them on this. He prods at the white nervousness surrounding Indigenous protocols and anxieties about causing offence through sheer ignorance. Most of all, Jamieson subtly circles around the expectations his audience may have towards something we’ve come to call “Indigenous theatre”—what does that mean? Is it a label that liberates or confines? Can it do both?

If it has to be labelled, Namatjira might be thought of as postcolonial Indigenous meta-theatre; it doesn’t merely give voice to the history and experience of Aboriginal Australia but questions how that voice is heard, what conversations it is part of. It’s a rich celebration of a fascinating figure, but also one rife with irony: in recreating the painter’s rise and fall in heroic terms, Jamieson notes that this is “the story whitefellas want to hear… the only story people seem to remember.” Alongside this drama we are given counter-narratives, most obviously incarnated through Jamieson’s co-performer Derik Lynch and the descendants of Albert Namatjira himself who work on a massive chalk mural dominating the back of the stage throughout the piece. They are reminders of the presences which persist beneath any official telling of the past, of the continuities which cannot be captured through biography alone, since a biography must perforce end, while a life’s legacy is more complex.

Timothy Ohl, Fiona Cameron, Look Right Through Me, KAGE

photo Jeff Busby

Timothy Ohl, Fiona Cameron, Look Right Through Me, KAGE

kage, look right through me

Another Malthouse production engages with the legacy of an icon who is still very much at work. KAGE’s Look Right Through Me took as inspiration the cartoons and drawings of Michael Leunig, an artist of whom no Melburnian would be unaware. But how to do justice to an oeuvre that carries with it the weight of many decades, and to an iconography that has very specific significances to the legion of fans Leunig has accrued over this time? To attempt an act of translation, in this sense, opens up the possibility of getting it ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ according to what meanings each individual reads into the artist’s work.

It helps that KAGE’s physical theatre methodology is very much based around images, but director Kate Denborough wisely avoids a literal staging of the Leunig with whom we are familiar. Rather, she has pieced together an independent narrative that seems to riff on the artist’s canon like a jazz take on a standard score; the cartoonist’s themes and characters rise and fall like a refrain, but the work itself doesn’t rely on recognition as its fundamental source of meaning-making. Of course, Denborough knows that in this city at least recognition will have its own potency, but this is a work that would make as much sense to an audience unfamiliar with its source.

On its own terms, Look Right Through Me has strengths and weaknesses. Some of its vignettes, which chart the course of an alienated everyman shadowed by his own childhood, are of unarguable impact: a rope swing dangling from a tree takes on the grim aspect of a noose; a patch of grass becomes both comforting bed and unsettling grave. It may be in the relationships between performers that Denborough’s work really shines here, and her choreography is both deftly athletic and emotionally charged, producing a very visceral realisation of the dynamics that connect and divorce humans from one another. At other times, such as an extended sequence of carnivalesque abandon, both the narrative and its emergent themes become more muddied, and it’s at these times that I found myself turning back to the artist and wondering if there was an element of his work that I was missing and which was vital to interpret the on-stage events. These were rare moments, however.

Mary-Helen Sassman, Liz Jones, Special, The Rabble

photo Marge Horwell

Mary-Helen Sassman, Liz Jones, Special, The Rabble

the rabble, special

The Rabble is a company equally interested in the power of image-based theatre, often producing far more disorienting results. In the case of Special, this isn’t a bad thing. For much of the shortish piece I didn’t really know what was going on, but this didn’t hinder enjoyment of it in the least. Mary Helen Sassman plays a belligerent, heavily pregnant woman harassed by her equally self-obsessed mother; they inhabit a strange space of hyperreal colour dominated by a massive mound of sand. Their interactions are fragmented, not quite nonsensical but obscure in nature, and the whole comes across like Beckett directing a children’s party. As their condition of static animosity plays out, however, a series of bizarre rituals is introduced whose intentions are left deliberately open to the audience, but which clearly possess an internal logic to which we are not privy.

With the slightest of changes Special could be wilfully obscurantist, an exercise in self-indulgence and a frustrating severing of signification and referent. But director Emma Valente somehow pulls it off marvellously, keeping her audience onside even while maintaining a constant distance between performer and viewer. She seems to acknowledge that we understand this mode of playmaking and expect more from absurdity than a basic deferral of meaning. Rather, the strangeness of what we see seems as real as any more rational presentation of plot and character; we may not understand the motivations that compel these figures, but how many of our own drives are unquestioned and equally odd, when put in the spotlight?

Thrashing Without Looking, Aphids

photo Ponch Hawkes

Thrashing Without Looking, Aphids

aphids, thrashing without looking

And into the spotlight is exactly where Aphids’ Thrashing Without Looking thrusts its audiences. Indeed, whether ‘audience’ is an applicable term here is moot. The work makes its participants both spectator and spectacle, simultaneously, as half the crowd is equipped with ingenious headsets that channel the footage being shot by a range of video cameras moving around the room. The other half direct the course of events, which are established according to the kitsch conventions of karaoke music videos—a romantic dinner for two, a turn at a pumping nightclub, a slow dance that ends in heartbreak. Those given the active roles are watching themselves at a distance while playing out each scene, and it’s a profoundly giddy experience. If the pleasures of classical cinema are of the voyeuristic kind, giving the passive viewer a sense of power over what is depicted on screen, this dynamic is up-ended when the gaze is directed back on itself.

Thrashing Without Looking was a short, sharp shock that managed to provoke questions about the place of the audience in a way quite rare these days. Hopefully it will go on to enjoy an expanded life in some form, as these are questions that deserved to be asked, and in this case at least, were a joy to be part of. (See also Jana Perkovic’s review)

Malthouse Theatre and Big hArt, Namatjira, writer, director Scott Rankin, performers Trevor Jamieson, Robert Hannaford, Derik Lynch, Kevin Namatjira, Lenie Namatjira, Michael Peck, Elton Wirri, Hilary Wirri, Kevin Wirri, designer Genevieve Dugard, composer Genevieve Lacey, costumes Tess Schofield, lighting Nigel Levings, sound design Tim Atkins, Malthouse. August 10-28; Malthouse Theatre and KAGE, Look Right Through Me, concept, direction Kate Denborough, creative collaborator Michael Leunig, co-devisers, performers Craig Bary, Fiona Cameron, Timothy Ohl, Cain Thompson, Gerard Van Dyck, composer Jethro Woodward, designer Julie Renton, lighting Rachael Burke, Malthouse. September 7-18; The Rabble, Special, director, Emma Valente, concept Emma Valente, Mary Helen Sassman, devisor-performers Liz Jones, Mary Helen Sassman, lighting, sound, composition Emma Valente; La Mama Courthouse, August 4-21; Arts House and Aphids, Thrashing Without Looking, creators Martyn Coutts, Elizabeth Dunn, Tristan Meecham, Lara Thoms, Willoh S Weiland, producer Thea Baumann, sound designe Alan Nguyen; Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall. 3-7 August

RealTime issue #105 Oct-Nov 2011 pg. 29