An inclusive vision of Australian women

Keith Gallasch: Karen Therese, Women of Fairfield

L-R: Maria Tran, Nat Randall, Emily O’Connor, Jade Muratore (Hissy Fit), Supreme Ultimate, Women of Fairfield

When I met Karen Therese, Artistic Director of Powerhouse Youth Theatre, for this interview she’d recently completed a season of Tribunal (read our review) at The Stables for Griffin (where she’d been a Studio Artist), Jump First, Ask Later (a new season of the 2015 Force Majeure-PYT co-production of a parkour-based work created by choreographer Byron Perry) is playing at the Sydney Opera House and a major PYT-MCA two-day event, Women of Fairfield, is only two weeks away. But, says an exhilarated Karen Therese, life is more than manageable and her company, Powerhouse Youth Theatre is well-resourced, in contrast with early ambitious works of scale that threatened to derail her career.

Western Sydney is alive with cultural activity driven by Powerhouse Youth Theatre, Urban Theatre Projects, FORM, Casula Powerhouse, ICE, Parramatta Riverside, The National Theatre of Parramatta and Campbelltown Arts Centre, plus the outreach programs of Carriageworks and MCA and much more. Significant local pressure has swung more state funding towards the west, and there’s the bonus of James Packer’s $30m gift (an attempt to assuage public discontent over his and the government’s mishandling of the Barangaroo development in Sydney Harbour; another $30m went to city arts). Much cultural activity in the west is socially oriented, dealing with disadvantaged suburbs, the needs of young people, refugees and new citizens, and drug and health issues. Other state and federal agencies provide funds for these ventures, allowing richer development and reach: “A three-year grant from the Department of Social Services was a complete game-changer for our company,” Karen Therese tells me.

Above all, the works produced by Powerhouse Youth Theatre and others transcend these particularities by making our fellow citizens visible, not as content or issue-bearers but as active participants and art-makers: “The work we create and the processes we engage are really supportive of individuals whether they become artists or not.”

Nothing could be more important as Pauline Hanson and her ilk not only aim to narrow our understanding of the complexity and richness of contemporary Australian culture but, by arguing for cessation of Muslim immigration, to prevent its civilising evolution. Powerhouse Youth Theatre’s Little Baghdad was revelatory: three nights (I experienced one) of performance and discussion over a meal shared with Iraqis of different regions, religions and cultural traditions, so far beyond the stereotypical image promulgated by mass media and politicians. I recalled that one of the Little Baghdad dinners focused on Iraqi women and wondered if that played a role in triggering the forthcoming event, Women of Fairfield.

Co-curated by Karen Therese and MCA Senior Curator Anne Loxley, Women of Fairfield is a collaboration between the MCA, Powerhouse Youth Theatre and NSW Service for the Treatment and Rehabilitation of Torture and Trauma Survivors (STARTTS). Facilitated by Jiva Parthipan, STARTTS Community Cultural Development Officer, each artist is working with the communities of Fairfield to create artworks which celebrate and reflect on the experiences of women. Karen Therese tells me about the inspiration for the event and the artists and communities involved.

Women of Fairfield

The Women of Iraq night, which I curated with Victoria Spence, is one of my favourite events. It became a little research event for how to deal with the enormous cultural sensitivity around working with women in Fairfield and an opportunity for women to talk openly about issues affecting them. Theirs is a very patriarchal culture. The stories were extraordinary. We traversed 80 years of Iraqi history—where women were part of a rebellion, were activists in the 1950s and 1960s, artists and actresses—all the way to contemporary Iraq where some are enslaved. In Fairfield, women don’t necessarily feel safe within the civic space. And there are homeless women. I was thinking about how our company would handle something like this, it’s huge, and had been discussing it with the Council. When the MCA came in, I pitched the idea: Women of Fairfield, Concepts of Home. Now it’s just Women of Fairfield. The focus is on the kind of performative site-based work I’ve done before.

I’m co-curating with Anne Loxley, the Senior Curator at the MCA for the C3West program. It’s been really great. I work with people, I do people and I do performative spectacle—big vision—but I’ve always worked with very limited resources. Anne gets the opportunity to make spectacle art-work. Together we can give Fairfield something it’s never had before.

Kate Blackmore & the Assyrian Community: All Wedding Wishes

Kate Blackmore, who worked on Little Baghdad, is creating a work with the Assyrian community called All Wedding Wishes about an Assyrian wedding. It’s a two-channel video installation that’s going to be introduced via an actual Assyrian wedding procession that will lead the audience through the site, an abandoned shop.

Claudia Nicholson & the South American Community

Claudia Nicholson is doing probably her largest sawdust carpet (an alfrombas, made of flowers, plants and dyed sawdust in Central and South America) to date, making it over five days in Fairfield Chase, a 1980s food hall. That will have a number of video artworks surrounding it and include the South American Women’s Choir. It will be hugely celebratory.

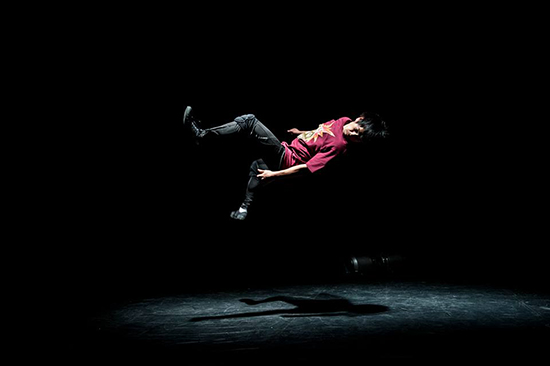

Hissy Fit & Maria Tran: Supreme Ultimate

We also have Hissy Fit (Jade Muratore, Emily O’Connor and Nat Randall) working with Maria Tran on a hugely ambitious project. Maria is potentially Australia’s foremost martial arts action woman. She’s in the new Jackie Chan movie and has just won Martial Artist of the Year. The work will play on two floors of a car park with interactive video by Toby K. And there’s going to be a martial arts mass action so we’re looking to get up to 50 people from the region to be involved.

Zoe Scoglio & Aboriginal, Assyrian and Khmer Communities: In The Round

Melbourne artist Zoe Scoglio is doing an extraordinary work bringing together Assyrian women, the Khmer women’s community and the Indigenous women’s community of Fairfield for In The Round. She’s run individual workshops with the women and recorded their singing. She’s placing those recordings inside three cars which will each be dressed by the women. With this amazing soundtrack, the cars will be driven around Fairfield to literally place women’s voices into the civic space. On the second night we’ll close down two roads and create a ‘revolution’ of circling cars in a cul-de-sac at dusk. Zoe’s work is about the cosmic— about revolution that can happen when three communities come together at a particular time of day. It’s a really exciting project that also gives the opportunity for our First Nations women to meet newly-arrived women and that’s the first time they’ve done that. I’m really interested in the Indigenous community meeting particularly the Assyrian community because they’re an indigenous Iraqi community. Both use language when they speak about their cultures, which are so ancient.

Unique gathering, unique expression

Seeing so many women come together from different cultures is something that actually doesn’t happen. Cultures tend to stay tightly together because everyone feels really vulnerable and protective. So Women of Fairfield will be extraordinary—all these women from so many cultures in the one space.

Johnny Do, Jump First, Ask Later, Powerhouse Youth Theatre & Sydney Opera House

INTERVIEW: FROM PERFORMANCE MAKER TO CULTURAL LEADER

I’ve seen a lot of your career, first when you were a contemporary performance maker and interdisciplinary artist. Since then you’ve become a creative producer and a cultural leader. It’s clear that some of your interest in this area came from growing up in Mt Druitt in Western Sydney. What was your impulse when you went to the VCA? Were you planning to become an actor or an animateur?

When I first got involved with PACT (Centre for Emerging Artists, Sydney), I realised I wasn’t going to be an actor. I was always interested in making work from my own ideas. I didn’t know about contemporary performance or devising but I’d put on my own shows from when I was really young. I didn’t apply to the VCA; I was invited into the animateuring course by Tanya Gerstle in 1999. I had also done The Journey [a year-long acting intensive with Gerstle at the Actors Centre in Sydney]. At the end of the Journey, we did a devised work and I got to write and perform things that I’d written and I really enjoyed that process. Eventually I found out about PACT and then very quickly was at The Performance Space and I saw Heterosoced Youth directed by Chris Ryan and I’ve pretty much made my own versions of that work ever since [LAUGHS].

This was a PACT production?

Yes, at the height of Mardi Gras. It was really big for PACT in 1997: a documentary work about young people coming out from different regional areas and telling their stories. I thought it was really exciting and a kind of cool contemporary work as well. Back then, it was pretty radical.

When I was at PACT they used to have ‘Zings’ and I created a work called whitegirlblackdreams, which was really a seed for so many things. I didn’t know a lot about Australian culture. I didn’t know anything about my own culture or my own family. So I performed it as a five-minute piece and Chris Ryan said it had “legs,” and I was, like, “What does that mean?” Not so long after that I went into the VCA and my sister and my mother unearthed family documents from which I started to create the ideas for Sleeplessness (background; review) which, in one form, became my graduate work. That began a whole exploration of Australian identity and realising that my mother was one of the “Forgotten Australians.” She grew up in a home in the care of the State. Now we have the Royal Commission, which my Mum is part of. She was also at the protests in Canberra demanding that George Pell come to Australia. So I’m pretty proud of her.

Sleeplessness was a fascinating combination of the intensely personal and a broader social political issue. And the work was also very exploratory in terms of form.

Yes, I look back at Sleeplessness now and think it was quite amazing how I was piecing together all the fragments in the making of it, and the experience. I couldn’t judge it when I was in it because it was bigger than an artwork. I feel like Tribunal is in the same kind of line but that I’ve found a way to create, maybe, a clearer narrative for audience about the complexity of Australian identity.

GATHERING GROUND

You’ve moved a long way from a very private work through large scale works and research to a cultural leadership role. Obviously, early on, there was something about works of scale that attracted you. You did Gathering Ground, a work for PACT with the Sydney’s inner city Indigenous community?

I did Gathering Ground twice. They were my largest works before Fun Park for Powerhouse Youth Theatre in 2014. I didn’t set out to make a huge spectacle; I wanted to make a walking tour. Do you remember Urban Theatre Project’s Speed Street (1999)? As a young artist, it changed my life because I grew up in a street like Speed Street and I first thought, you can’t bring people to a show in a street like this.

Gathering Ground was a collaboration between PACT and Redfern Community Centre and involved myself and Tracey Duncan who was running the centre. The idea was to bring non-indigenous people to The Block in Redfern. These were ‘reconciliation’ works, I suppose—a lot of Indigenous people I know don’t like that word. It brought non-indigenous people to an Indigenous space, often for the first time. The relationship I set up with Tracey was really strong. We talked for about three months. We were women of similar age. We cemented the idea of a history/ceremony/protest and telling the story of The Block and of each building, touring the audience and putting different artists in charge of developing works. This was 2006 and pre-Apology. The idea really took off. By the third night, thousands of people had come. It was an extraordinary experience. Then we did it again and Lily Shearer came on board.

RACE & CROSSING THE THRESHOLD

We thought, maybe 100 people might come. The whole idea emerged when Regina Heilmann was PACT Artistic Director and I got the job as Community Cultural Development Artist. She said, “Well, I’ve got to take you to all the youth centres around Redfern and to The Block.” We walked there and I got scared when I stepped over that threshold. I kind of checked myself and went, “What am I afraid of? I’m from Mt Druitt!” That was my innate racism coming out and I thought, “I want other people to have this experience of stepping over.” On opening night we thought, “No-one’s here. We were right—no-one’s gonna come.” And we looked over and there was this big crowd outside Redfern station and we had to say, “It’s over here. You can come over.” The last night along the whole of Eveleigh Street was crowded, you couldn’t move.

Where did that take you next?

I needed a break. That was really intense. The first one was really exciting to do. With the second one in 2008 the politics really got on top of it. It became really complicated. I think also at that time there wasn’t a lot of knowledge around how these relationships work.

At the same time, I was still interested in making works. I’d done Sleeplessness and I did a little piece at UTP called Misspent Youth and that led me to the idea for The Riot Act (2009) with Campbelltown Art Centre. I worked on that for a few years. I also did Constellations at PACT, which was my homage to Heterosoced Youth. After a family tragedy which impacted me hugely, I was ‘out’ for a couple of years. I wanted to make works of scale but the issue wasn’t so much the scale as the complexity. I was exhausted after Gathering Ground. I was exhausted after The Riot Act.

TURNING TOWARDS HOME

I woke up one day in 2010 and realised that I wanted to base my practice in Western Sydney. As an artist I always felt a little bit different from my peers. I never quite felt like I fitted in, feeling like I should be making work like The Fondue Set or Martin del Amo did. I was a bit too serious and everything was hard as well. Small pieces aside—The Walk, Waterloo Girls and Comfort Zone—I stopped making large works. I needed to make a really small work with Indigenous people—Waterloo Girls—after Gathering Ground, just a simple work that helped me realign my politics. Then I performed in my own show, The Comfort Zone, which was a good thing to do. I thought, I’m just going to step to the side for a few years. So I went and did my Masters with Professor Sarah Miller at the University of Wollongong. Former Performance Space Director Fiona Winning was also a mentor. I was about to stop working because life was a little bit hard at that point. She was really frank with me as a young artist and gave me some tools with which to work sustainably in the community.

CULTURAL LEADERSHIP GRANT

I got the inaugural Cultural Leadership Grant in 2010 from the Theatre Board of the Australia Council. My focus was not on outcomes; it was to get feedback from all the people who’d supported me and knew my practice and then go to New York with a vision to explore and research innovative practice across disciplines and across cultures. So I was at PS122 for a period of three years in and out. That was really fantastic. It was at the end of the building redevelopment so they had a 30_year festival and had alumni short works nights. So I’d be producing The Wooster Group and Phillip Glass and Thurston Moore. I got a lot of inspiration from managing and curation—I really wanted to work in Western Sydney but to come in with a dynamic approach. Conflict management has become a really big part of what I do. Then there’s business. And you have to be creative.

FUN PARK

So it all started coming together for you?

Yes. In New York I was looking at a new picture and with my Masters I was reflecting on the past and untying a lot of it to create a sustainable practice to enable me to move forward in Western Sydney. And then, around that time, I had the idea for Fun Park and applied a number of times for the $80K Australia Council Creative Producer Fellowship. I didn’t want it to be a project thing; it would pay me a wage for a year to develop and commence Fun Park. After a lot of hard work and making connections it got up with Sydney Festival.

I was able to put in place everything I learned through my Masters about sustainability. It was also about me going home, making a work in my place. That was really big. In Sleeplessness I remember I uttered the words “Mt Druitt.” You don’t tell people you’re from there. For me to invite 2,000 people to Mt Druitt was huge. (see Virginia Baxter’s review of Fun Park)

In my Masters I was studying ideas of comfort and failure in performance companies like Forced Entertainment (UK) and Goat Island (USA). Those guys have generated a lot of writing about failure in their work. Failure is just a radical opportunity to change. And I think coming from Mt Druitt I wasn’t as confident maybe as everyone thought I was and I was always worried about failing. Every time I performed. I’d work really hard and try my very best and then afterwards give myself a hard time. [LAUGHS]

You’re over that, I hope?

I am. Absolutely. With Fun Park everything was kind of constantly collapsing because it was really complicated. But every time something else collapsed, I’d think, well, that’s interesting; now, what haven’t I thought of? And that’s completely how I think now. Working in Western Sydney I feel more aligned as an artist and as a person that I’m kind of with ‘my people.’

And you’ve reached out to a lot of new people too, like the Iraqi community in Little Baghdad.

I share parts of their history and I suppose through my research in my art and my personal experience, I understand to a degree some of their experience and I’m able to work with them in ways that perhaps other artists aren’t.

The scope of your approach is considerable, embracing multiple forms, communities, issues.

Yes, I can do whatever I want in all my capacities because I have worked across a lot of artforms and I can speak all of those languages to some degree. So it wasn’t just luck—I was really on a five-year plan to base my practice in the west—and I ended up with my own company. It couldn’t be better.

Karen Therese

Women of Fairfield, co-curators PYT Artistic Director Karen Therese, MCA Senior Curator Anne Loxley; a collaboration between Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Powerhouse Youth Theatre, Fairfield (PYT), and NSW Service for the Treatment and Rehabilitation of Torture and Trauma Survivors (STARTTS), presented with the support of Fairfield City Council, Fairfield, 7, 8 October, Free, 6.30-9.00pm

RealTime issue #134 Aug-Sept 2016