Antistatic and the beast

Eleanor Brickhill: Antistatic 99

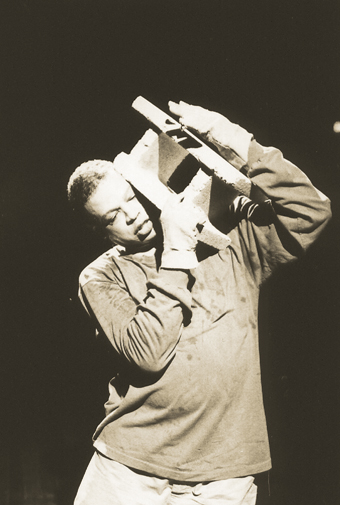

Ishmael Houston-Jones, Without Hope

photo Mark Rodgers

Ishmael Houston-Jones, Without Hope

Eleanor Brickhill asked Ishmael Houston-Jones about his impressions of antistatic 99.

I often feel like a member of a band of vagrant minstrels, criss-crossing the worldwide countryside of postmodern dance. We steal into a town, dance for our supper and a place to sleep, and then move on. Because the friendly villages are few and well-known to members of my merry band, we invariably run into each other at semi-regular intervals. I might see David Z in Havana, then David D in Glasgow; I’ll have a dance with Jennifer M in London, and the other Jennifer M in Northern Venezuela; I’ll watch a performance by Lisa in Arnhem, and she’ll watch my dress rehearsal in Sydney. This has been my life for 20 years.

Of course New York is my home. It’s where the answering machine is. It’s where the cheques with a variety of postmarks come. It’s a city that inspires and drains me. It is a city, however, that will never support me, nor the majority of my downtown dance compatriots. Thus roaming from small festival to small festival has become a necessary pleasure for survival. While the road can sap as much energy as being broke and over-stimulated in Manhattan, it does make it possible for me to make my work.

In April 1999 I travelled midway around the world to take part in the second antistatic festival in Sydney. As a safe haven for dancing, this turned out to be a welcoming and genial way station. The production of my performances at The Performance Space was done with exacting professionalism combined with compassionate attention. The programs were well curated. While audience size varied, it was clear that the organisers had done a lot, through receptions, an attractive flyer and other publicity, to bring out the New Dance public in Sydney.

The workshop I taught, “Dancing Text/Texting Dance”, were well run by antistatic. It attracted a near perfect assortment of those interested in sharing my process for the 2 week period. The “dancing paper” presented by Susan Leigh Foster was thought-provoking and added a context for the work that was being presented and taught. The events attracted (curious) reviews in the mainstream press.

As an antistatic participant, I feel the main fault of the festival was its overabundance. During the 3 weeks, there was very little downtime or space for processing. With workshops running 5 days a week for 6 hours a day, and a variety of shows, showings, lectures etc taking place in the evenings and all weekend, I often found myself feeling tired and stretched (or guilty for skipping out on an event). This may have had to do with the fact that this was my first journey to Australia, and I wanted to get a little sight-seeing and night life into my itinerary. Also suffering from this being my virgin voyage Down Under, is my ability to adequately critique the breadth of the local work. The program of which I was a part also featured pieces by fellow New Yorker, Jennifer Monson, and the Melbourne duo, Trotman and Morrish. This program was varied in its scope within the narrow frame of “new dance.” The works evocatively contrasted one another, while they seemed to accidentally provide some complementary subtext for the evening.

The works on the following weekend were a different story. Although Lisa Nelson is from the United States and Ros Crisp is from Sydney, several of my students described the program as a “very Melbourne evening”. While the works varied greatly one from another, they had a disquieting similarity of tone. I found this to be most true with the “the gaze” and how it was used, or not used. Except with Nelson, the only non-Australian on the program, there seemed to be a determined effort to not acknowledge the audience through any overt eye contact. This lent an air of “art school lab experimentation” to several of the pieces. Again, I’m not sure if I’ve seen enough local work to justify even this stereotype, but this inward focus did seem to be a less refined echo of the performance personae of Russell Dumas’ dancers, whom I saw as part of antistatic at The Studio at the Sydney Opera House.

Ishmael Houston-Jones, Rougher

photo Mark Rodgers

Ishmael Houston-Jones, Rougher

What I found different about antistatic, as opposed to, say, The Movable Beast Festival in Chicago, was its lack of both artistic and ethnic diversity. In 1998, at Movable Beast—a small festival of new dance in its second year—I performed 2 of the same pieces I did at antistatic. But while there was an emphasis on “pure movement” pieces, there were also works that veered toward performance art, multimedia spectacle, spoken word, drag, cabaret, and site specific. The latter 2 genres were encouraged by having multiple venues for the festival. While the main performances took place in a traditional black-box theatre, each festival participant was required to also present “something” on a tiny stage in a jazz club between sets, and also to make a site specific work for the Museum of Contemporary Art’s 24 hour Summer Solstice celebration.

Another difference was that all performers taught, and there was a lot less teaching by each person: 2 days apiece for the visitors; one day for the Chicagoans. While this greatly lessened the intensity of the workshop experience, it did allow for the participants to take one another’s classes, and for the students to get a taste of many different approaches to making work. I think something between the antistatic workshop stream in which a student signs up for one teacher for the entire 2 week period, and the Movable Beast’s workshop sampler would be preferable.

A striking difference between the 2 festivals was in their ethnic make-up. This is influenced by my American perspective, but it is not likely that such a festival in the States would ever be as “white” as antistatic was [Yumi Umiamare and Tony Yap were also antistatic participants. Eds.]. There were no international artists involved with Movable Beast, but besides myself, there were African-American, Asian-American and Hispanic artists teaching and performing. Several were gay. The teacher/performers came from 5 states outside Chicago. Like the audiences and artists of new dance, the majority of workshop students were white, but there was some ethnic diversity in most of the classes. While I try not to place an over-arching significance on these statistics—and of course I realise the demographics of the 2 countries are very different—I still feel that some creative outreach to different populations allows a festival to be more richly diverse and less restrictively insular.

antistatic was a very positive experience. It allowed me to present my work through performing, teaching, and discussing it with a new community in a very nurturing environment. It can only get better as a festival by widening its embrace of new dance.

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 14