Aromatics of thought

Keith Gallasch: Cat Jones, Scent of Sydney

Cat Jones’ Scent of Sydney, Sydney Festival 2017

photo Jamie Williams

Cat Jones’ Scent of Sydney, Sydney Festival 2017

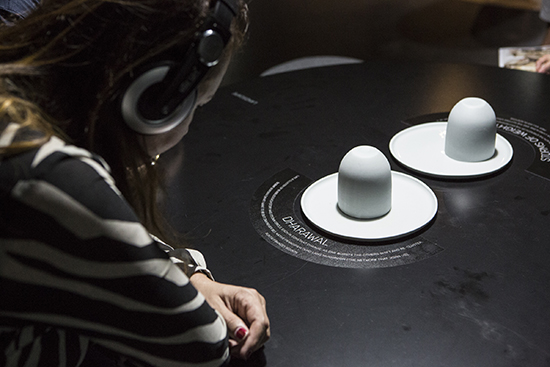

In Cat Jones’ Scent of Sydney people speak about the smells they associate with Sydney and what they say about the city. Visitors to Carriageworks listen on headphones to recordings of the speakers and sniff the artist’s responsive olfactory concoctions. Smell is the most underrated of our senses, long demoted to the status of an evolutionary leftover despite the enormous amount of perfuming, deodorising and sanitising we invest in. Science increasingly tells us that smell can determine mating and social behaviour, even if it’s less of a determinant than for our earlier selves. Freud, and others, thought that when we became bipedal we lost direct oral and olfactory contact with our aromatically potent ‘nether regions’ and hence the power of smell was reduced as other sensory signalling gained dominance. It’s good to see smell making a comeback whether in the savouring of food and wine or, here, art.

Having grown up in dry oven-heat Adelaide, I’ve found humid Sydney summers to be sub-tropical fecund, making for a smelly city, ideal for investigation. Cat Jones’ contemplative Scent of Sydney yields personal associations prompted by the recorded reflections of 10 citizens pondering themes like Competition and Extravagance. Sitting around five circular tables (each labelled with the names, aromas recalled and interests of two speakers), we listen on earphones and sniff at related odour-laden ceramic bowls, joining fellow sniffers in a subtly and comfortably staged olfactory celebration. At the room’s centre is a large circular carpet, comfortable chairs and “live art” consultants in aprons and with clipboards, ready to answer questions and take aromatic queries to Jones. Low lighting, soft grey woodwork and materials reduce distraction, enabling close listening and smelling. It’s a pleasure to observe the patience and attentiveness of listeners, the pockets of quiet conversation and individuals browsing a row of computer screens that reveal the responses of visitors and commentators.

Over two visits I listened to most of the recordings. A few focus incisively on a number of smells and their significances, for some one aroma triggers a huge wave of recollection, for a few it seems to play a minimal role—either that or, as for many of us, it’s difficult to talk about smell with any definition. A favorite of mine was the account by Michael Darcy (a specialist on social housing policy and the connections between social disadvantage and place) itemised under Competition, of how the aromas of industries once mapped the city—hops, biscuits, industry, coffee grounds, the abbatoir—but no longer. His account centres on the brewery once located on Sydney’s Broadway—now a shopping centre and apartments. He recalls hops being cooked, “almost burning the nostrils, but rich and chocolatey.” Beer was made and consumed by a then well-paid working class, its production coming about as close as you could get to Marx’s notion of “unalienated labour” under capitalism, says Darcy. That class, its industries and their aromas have been displaced and scattered. There’s a certain beeriness to the aroma in the cup and, I suspect, other smells my nose is not fine-tuned enough to name.

Cat Jones’ Scent of Sydney, Sydney Festival 2017

photo Jamie Williams

Cat Jones’ Scent of Sydney, Sydney Festival 2017

For filmmaker and feminist Pat Fiske, a 1970s builder’s labourer, it’s wet concrete that triggers powerful recollections of a changing Sydney, of emergent feminism, of working on building sites and beginning to make the documentaries that would shape her activist career. To this day, she says, when walking past a site she immediately knows how long ago the concrete—”a musty, dusty, heavy smell”—had been poured. I acutely recognise the smell of damp concrete in the ceramic bowl from childhood recall of new houses springing up around ours. Writer Anne Summers recalls the aroma of brown rice being cooked in the 70s to feed women in refuges—established against the odds by activists in “a totally corrupt Sydney” dominated by developers. Also lingering are the smells of mops and balloons, of cleaning and celebration. There’s little to celebrate now, says Summers, when the NSW Liberal Government has reduced the number of refuges and rationalised their management at the height of the challenge to domestic violence. Leaves a nasty smell.

Jones’ rendition of the smell of “fireworks, sweating bodies and a whiff of amyl nitrate,” the odours that accompany photographer William Yang’s contribution—about the 80s and 90s, AIDS and Mardi Gras—is pungent. Yang doesn’t detail the characters of the aromas. Other speakers are more specific. Writer Elizabeth Farrelly, a specialist on architecture and urbanism, delights in “a bushfire morning,” the smell of smoke leaking into the city, a reminder of where the Australian magic is, in the bush, she says, but the aroma can also be alarming . She ambles her way to her topic, Extravagance, arriving with a fascinating example that sidesteps the familiar examples on Sydney indulgence: solemn mass in a High Anglican Church in Redfern, its frankincense—”earthy, magical”—supplanting the stink of vomit outside and inducing a sense of “pagan ancientness” and transcendence that is “almost therapy.” Storyteller and documentarian Patrick Abboud identifies himself culturally in terms of food aromas elemental to the ingredients of Lebanese cuisine—thyme, olive oil, oregano, marjoram, caraway, sumac, sesame and bread—but juxtaposes these with the smell of “a fresh-washed jumper,” belonging to a fellow adolescent he was deeply attracted to. He comes to learn that in coming out to his parents about being gay that his struggle is not, however, binary, and that shame and anger are not necessary outcomes.

For Auntie Fran Bodkin, a descendant of the D’harawal people of the Bidiagal people, educator of Dharawal knowledge and holder of a Bachelor of Arts and Sciences (including Environmental Sciences), the scents of boronia and native frangipani—”my native plant”—trigger memories as well as concerns. An uncle told her, “The Earth will live forever, but we’ve go to help it. The Earth is our mother.” The senses also affirm knowledge, she says, that is at once inherited and scientific—for example, “bellbirds tell us which land is under pressure.” The connection between sensory alertness and environmental responsibility is powerfully made and resonant with Professor William Gladstone’s ecological sensitivity associated with briny air, rotting algae and the power of electrical storms.

Cat Jones’ Scent of Sydney, Sydney Festival 2017

photo Jamie Williams

Cat Jones’ Scent of Sydney, Sydney Festival 2017

Listening to the work’s quite long recordings, I wondered a number of times when mention of the particular smell or smells key to a speaker’s thoughts about Sydney would actually manifest. Sometimes that mention seemed incidental or, even when significant, briskly passed over. At other times the connection was incisive and worth the wait. Either way, whether for an iteration of this work or a new one, greater focus and economy in recording and editing would be welcome. I was also uncertain at times about precisely what I was smelling, despite the tabletop cues; though I think I fared better on my second visit.

Scents of Sydney, alongside Imagined Touch and The Encounter, is part of a wave of works emerging over the last decade or so that engage audiences either by limiting or intensifying sensory impact, usually in order to deal with a subject, here the character of Sydney, in a new way while simultaneously expanding our sensory responsiveness, or, as in Imagined Touch, making sensation (or its loss) the subject. Jones and her collaborators have created a fascinatingly distinctive work, one with a quiet sense of ceremony, olfactory stimulation and insights into the intricate entwinings of sense, memory, thought, feeling and place—emotional, social, political and environmental. Engrossing and altogether memorable.

–

Sydney Festival 2017: Scent of Sydney, artist Cat Jones, speakers Patrick Abboud, Auntie Fran Bodkin, Dr Michael Darcy, Elizabeth Farrelly, Pat Fiske, Professor William Gladstone, Sarah Houbolt, Lyall Munro Jnr, Anne Summers, William Yang, live artists Rebecca Conroy, Sumugan Sivanesan, Nick Atkins, Maria White, exhibition design Pip Runciman, lighting design Neil Simpson, ceramics Naomi Taplin; Carriageworks, Sydney, 7-29 Jan

RealTime issue #137 Feb-March 2017