Art from the heart

Danni Zuvela

Trish Adams, machina carnis

You enter a large, very dark room illuminated only with strategically placed red down-lights. To the left hang 2 swathes of diaphanous fabric: small images of red cells floating against blackness. Towards the right hand corner stands an object curtained off by a large acrylic sheet hanging from a chrome rail. Through the heavy red plastic you can make out a horizontal hip-height structure—a bench or table. The room is quiet but for a dull, distant hum. Suffused with the pure red light and cordoned off, the bench looks a little like a modernist altar.

As you approach you see it is a bed of the kind found in doctors’ surgeries, with a surface of padded black no-nonsense vinyl, and thin steel legs. A large flat monitor is positioned horizontally above one end. Once you’re on the table, your head positioned beneath the screen, a circular image is projected—a petrie dish—full of smaller shapes. Placing the hanging stethoscope microphone over your heart, you watch the cells ‘respond’ to the pulse as the beats boom and echo in the gallery space. The latest in Trish Adams’ explorations of biotechnology, machine carnis continues to explore the “vital force” of biology, this time through an immersive experience bringing together audience participation and actual living cells.

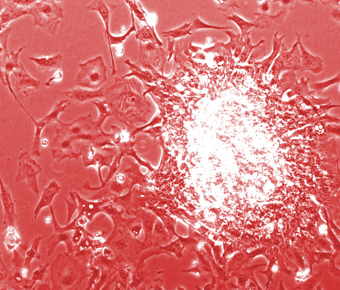

During her recent collaboration with the School of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Queensland, Adams “was inspired by the latest research that indicates adult stem cells are capable of “changing fates and becoming other types of cells.” For the installation, “stem cells were taken from my blood and cultured in the laboratory.” With the help of scientist-collaborator, Dr Vic Nurcombe, these cultures were incubated with special substances, “and after 5-6 days my stem cells developed into heart cells. Subsequently they began to beat, synchronise and cluster so that I could watch them throbbing in real time under the microscope.”

The pulsating aqua, white and maroon images shown on the monitor above the participant and on the hanging translucent screens are digital videomicrograph images of those cells, pulsing in time to the prone viewer’s heartbeats. Also evident in the microseconds after each beat is a faint image taken from a webcam above the bench of the participant’s face, combining imagery of the outside and the inside of the body. Adams hopes that viewers will explore “their personal reactions and interpretations whilst interacting with the cardiac image data which responds to their presence.” The viewer can also “observe that cultured cardiac cells have grown into a microscopic simulacrum of a beating human heart, as if the vital, functioning interior engine of their own body were laid bare before them.”

Adams’ ongoing investigations into corporeality and the materiality of the human body and probing of “both the unknown possibilities of virtual presence and recent developments in biotechnology such as stem cell research” are informed by her sculptural background. This is evident not just in the exquisite simplicity and attention to detail of the objects—bench, microphone, monitor, curtain—or the confident, dramatic way they are assembled, but in the manner normally abstract scientific ideas and contemporary debates are performed in the objects and processes of the work.

Brilliant sculpture often invites touch and machina carnis is constituted not by rhetorical address but by actual touch. The stethoscope microphone is rather sensitive to pressure—too little and it won’t register, and too much will prevent the movement of the diaphragm which is necessary to make normal breathing audible. The genuine interactivity which places the viewer right at the centre of the work is also an unusually sensual experience (it’s not every day one bares one’s breast in public in the name of art!). There is a delightful synaesthesia in ‘seeing’ one’s heartbeat, too.

Unusually for video art, in machina carnis the video, rather than being the defining activity, is sensitively incorporated to enhance the interactive experience. Adams’ sculptor’s eye is evident: she wanted “to work with moving images. I wanted to be able to create environments or ‘sensitive spaces’ that took advantage of the fluidity, ambiguity and ephemerality offered by mediums using projection as a counterpoint to materiality and corporeality.”

The restrained palette of the entire installation and complex videomicrograph images underline the critical role contemporary 3D animation has had in organising our perception of the appearance of cells. Biotechnology, as a place where epistemological, ontological and political debates converge, is a key concern of a number of artists seeking to challenge and complicate often simplistic views. This intimate engagement of the participants provides a novel and timely insight into genetic technology, which Adams hopes will “re-privilege the aesthetic experience of corporeality in the discourses surrounding genetic manipulation.”

Trish Adams, machina carnis, installation, Rehearsal Room, Brisbane Powerhouse, July 5-9; quotations from the writer’s discussion with the artist.

RealTime issue #68 Aug-Sept 2005 pg. 35