Art & massacre: the necessary memory of loss

Miriam Kelly: With Secrecy and Despatch

Dale Harding, Mardgin dhoolbala milgangoondhi – rifles hidden in the cliffs, 2016

Dharawal kiskisiwin (remembering Dharawal) is a digital animation of Google map images charting the journey from the Dharawal Land Council along the roads, past the brick homes, through fields and into thick eucalypt scrub. We arrive at a scene of cliffs on private land in Appin, not far from the outer Sydney suburb of Campbelltown. In this animation, the cliffs are marked with a yellow pin titled “Site of Appin Massacre.” A parabolic sound cone above the animation wails an offering in Cree and English to the Dharawal for their loss. This pin is not just a mark made as part of the recent artwork by Canadian First Nations artist Cheryl L’Hirondelle—seeking to stand in solidarity—but in fact one of many such points that can be found on multiple Australian maps with a quick internet search: maps that identify over 30 such sites of frontier atrocities on the mainland that range from Appin in 1816 to Conniston in the Northern Territory in 1928.

“The upper scene depicts a massacre that took place early in the 20th century,” explains a text about the work of Gija artist Queenie McKenzie, which she painted in 1996 to map one of many stories from the Kimberley. “It is part of Aboriginal oral history but is not reflected in Western written histories of the area.” This statement is, in essence, the key curatorial premise of Campbelltown Arts Centre’s With Secrecy and Despatch; a bold political response, it protests the national amnesia about colonisation and, in particular, the denial of massacres—stories of great loss that have been written out of our nation’s history. This is an undeniably important topic deserving of attention. The only issue is that the exhibition presents this notion at such volume and from so many focal points that it could have in fact benefited from being three separate shows.

Visitors are welcomed into the gallery by two imposing black walls that block the standard sightlines through to the sunlit garden. The black vinyl title and introductory text on these walls is intentionally hard to read without making an effort and moving across the space. It is a clever device that gives the text the appearance of having been etched into the wall, as on a stone memorial, and implicates us in a responsibility to seek out the knowledge it offers. These words explain that using April 17 2016—the bicentenary of the Appin Massacre—as a catalyst (it could have been exhibition one), this show features 10 newly commissioned works by First Nations Canadians and Aboriginal Australian artists to “not only speak of the Appin Massacre,” as curators Tess Allas and David Garneau explain, “but to brutalities that have occurred globally” (exhibition two). A three-year-long project in the making, With Secrecy and Despatch—titled after the words Governor Lachlan Macquarie used to describe the way in which the Dharawal people were to be forcibly removed from their land and killed if they resisted—also brings together 13 existing works by 11 Aboriginal artists that map massacres across the country, on loan from three major cultural institutions (exhibition three).

Fiona Foley, Annihilation of the Blacks, 1986, courtesy National Museum of Australia

Regardless of the show’s scale, there is one very strong and pertinent leitmotif that, as you enter the large open-plan central gallery space, is made immediately and unapologetically apparent; it is just simply ‘massacre.’ The earliest work in the show, Fiona Foley’s 1986 sculpture Annihilation of the Blacks, commands centre stage and sets the tone. A political work at its outset, Foley’s sculpture—as Allas explained in her curatorial walk-through— is now also bound up in the Howard-era History Wars once its removal from public display at the Australian Museum had been requested.

The work comprises a branch suspended between two stripped-bare trees from which hang nine coarse ropes, of the type used to dry fish in the tropics. Only on this occasion, the ropes are nooses that suspend nine small, black, carved wooden bodies, while a single white faceless figure stands by below. In this display dramatic lighting scatters shadows of the bodies across the plinth below and well beyond, over the floor of the gallery, so that visitors cannot avoid their presence. Like McKenzie’s, Foley’s work was made in reference to a story passed down via oral history; relating the atrocities at Susan River in Queensland, as well as the actions of colonial soldiers in suspending the bodies of those killed from trees as a warning to any survivors. Each work in this show carries this intensity, this weight of words spoken and unspoken, stories that have been told—as this show reminds us—in contemporary Aboriginal art for over 30 years.

Tony Albert, Blood water, 2016, courtesy the artist and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney.

Colour is also used to dramatic effect in tying together the show’s 30 diverse works. Allas explained that a distinct shade of red emerged independently in the commissioned works of Tony Albert, Vernon Ah Kee, Frances Belle Parker and Marianne Nicolson, as well as already being present in the works of Judy Watson, Freddie Timms and re-enforced in a second state of Laurel Nannup’s woodblock print. It is of course a confronting and unmistakably ‘bloody’ shade that was also selected for the exhibition room brochure’s paper. As well, the same dense matte black of the entrance walls that defines Albert’s works punctuates the soft grey and white of the main open gallery space, as well as all four smaller rooms off to the sides. This darkness sucks the light out of any perception of depth in these rooms and there is a sense of claustrophobia, particularly in the space featuring works by Nannup, Ah Kee, and Dale Harding.

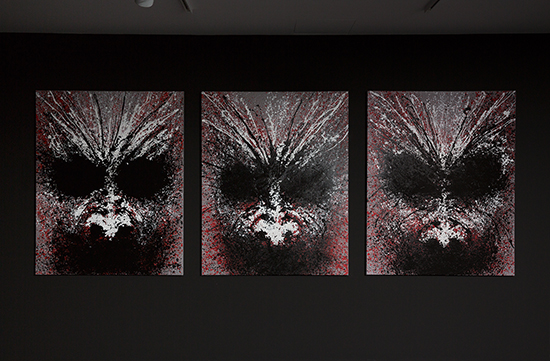

Harding’s commissioned installation, Mardgin dhoolbala milgangoondhi—rifles hidden in the cliffs 2016, presents just that: a ‘cliff-face’ of rawhide marked with ochre outlines—“splatters,” Allas calls them—of handprints, shackles and period guns. Indistinct in dim lighting, like a sepia-toned recollection, for Harding this work honours both the loss of and the acts of resistance by his ancestors, for whom the sandstone cliffs of their country in central Queensland became “keeping and hiding places.” On the opposing wall, Ah Kee’s ‘portraits’ of violence, Brutalities 2016, offer the singular refection in this show on the image of the perpetrator. The three images present faces dehumanised, almost dematerialized: eyes and mouths blackened depths with all surrounding form and skin seemingly blown apart.

Genevieve Grieves, Remember, 2016.

In this room the air feels thick and sound is muffled by the carpeted floor; visitors speak in whispers. An awareness of periods of silence weighs heavily in this exhibition as it is punctuated every 15 minutes by the crackling melody of God Save the King and a gunshot, marking the start of Adrian Stimson’s two-channel video AS ABOVE SO BELOW 2016, a drone footage homage to the landscapes that bore witness to the massacres in Canada’s Cypress Hills and in Appin. Stimson’s loop is accompanied by the haunting voice of a child repeating “remember,” part of Genevieve Grieves’ memorial installation of the same name. At other times, and across other spaces, it is also possible to glean Nardi Simpson and Amanda Brown’s commissioned soundscape: the whip of a lyrebird and an eerie melody that echoes a child crying—the sound believed to have given away the Dharawal people’s hiding place to colonial officers.

Tying the concept of this incredibly ambitious and timely project in with a local atrocity, the Appin Massacre, its bicentenary and with an international residency is the brilliance and complication in the messages the show leaves us with. What is unequivocal, however, is the overall greater historical and political purpose. In her commanding video work HUNTING GROUND (2016), Julie Gough instates snippets of accounts of violent encounters from over 170 texts about violent encounters found online over just the one mapped record that references massacres which took place across Tasmania. She writes in the accompanying text, “The evidence of what happened here is often marked with absence…absence of an acknowledgement of these ‘difficult’ histories…” Secrecy and Despatch not only acknowledges, it adds a much needed layer of visual, conceptual, personal and political context to those pins that map the true histories of colonial Australia.

Vernon Ah Kee, Brutalities, 2016, courtesy the artist & Milani Gallery, Brisbane.

You’ll find more images from the exhibition and an interview with the curators here.

–

Campbelltown Arts Centre: With Secrecy and Despatch, curators, Tess Allas (Australia), David Garneau (Canada), Campbelltown, 9 April–13 June 2016

RealTime issue #133 June-July 2016