Artgaming the art/video game nexus

Liam Gibbons

,_Tale_of_Tales.jpg)

The Graveyard, 2009, Tale of Tales

Are video games art? It’s a question which, like most that can be answered with a simple yes or no, is relatively uninteresting. It’s also a discussion which both enthusiast and mainstream games discourse has largely moved beyond. Despite this, artists continue to interrogate the line between art and game by producing and sharing small, personal “artgames.”

While the aforementioned debate is for the most part over, art and games are still treated as separate entities in many ways. To understand this divide is to understand artgames. According to certain commentators, big-budget, mainstream video games simply cannot be art and therefore we need a separate category: we need artgames. So what places artgames closer to art than to game? From the outset, they’ve featured a distinctive or highly stylised aesthetic, which is perhaps in response to the tech-centric desire for hyperreal reproduction of physical space which permeates mainstream game production. They explore a distinct artistic, cultural or political condition, usually illuminated via artist statements and post-development reflections. They are the product of an individual or small collective with a specific vision: artists producing art.

The Graveyard

Almost above all, though, is a de-emphasis of the (still disputed) formal elements which traditionally constitute a video game. One of the foremost artgame partnerships, Tale of Tales, explicitly rejects rules, objectives and challenges. Their Realtime Art Manifesto (2006) called on artists to challenge dominant notions of what constitutes video games. From this thinking came The Graveyard (2009), a short game in which players guide an old lady through a cemetery. It’s a slow, laboured experience, but her frustratingly slow movement encourages empathy. Finally reaching the bench at the end of the path is a bittersweet relief, where the woman sings of dead friends and the constant shadow of death.

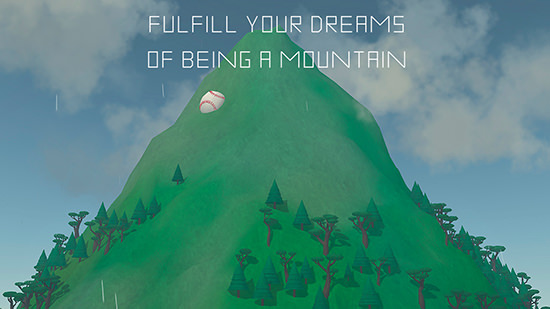

Mountain, 2014, David OReilly

Mountain

The anti-game sentiment of earlier works like The Graveyard has been reflected in similar manifestos and movements across the past decade of game design, with ideals which in turn can be traced back through the disruptive and playful art of the last century. Just as video games in general drew on ideas about audience participation and repeatable, sharable performances from Fluxus, artgames continue the Dada tradition by interrogating the artistic and cultural value of video games. Like Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) almost 100 years before it, David O’Reilly’s Mountain (2014) presents a game seemingly without purpose. It begins by asking the player to produce a series of drawings in response to key words such as “soul,” “children” or “the past.” They are then introduced to the mountain which gently rotates and occasionally makes comments, ranging from complete nonsense to the deeply profound as day, night, rain and snow pass over it.

By shedding almost all interactivity, Mountain asks: what is the purpose of such a game, and why were we asked to pay money for it? Tellingly, a large group of players simply didn’t know what to do with it. Mountain barely seems to react to input from either mouse or keyboard, save for some spinning of the in-game camera and some lonely piano notes echoing across the scene. It doesn’t have any discernible objectives, and there’s a complete lack of challenge or obstacle. In the same way Dada questioned what was expected of early 20th century art, Mountain questions what is expected of early 21st century video games.

The rise of virtual galleries

The link between contemporary video games and contemporary art is stronger still in the art of New Zealand-born game maker Pippin Barr. Virtual galleries are becoming a staple for artgames, appearing in everything from the work of English developer Strangethink https://strangethink.itch.io/, to Los Angeles-based collective The Arcane Kids, to indie darlings Cardboard Computer (have a look at Kentucky Route Zero). But the motif is a particular focus for Barr, whose recent work V R 2 (2016) virtualises Donald Judd’s 100 untitled works in mill aluminum (1982-1986) to explore notions of digital presence and absence in game spaces.

V R 2: virtualising art

V R 2 consists of two virtual gallery spaces, each populated with 24 featureless white cubes. At the entrance to the first gallery is a sign, describing the contents of each cube, from a 13-word sentence to a sound recording of rain falling. The second building has a similar sign, with slightly different labels: 24 instances of “a cube in default material.” Barr states on his blog that the work isn’t really about playing a joke on the player, but rather an exploration of “invisible” objects in a virtual space and whether or not they create the same sensation for the player as Judd’s physical version did for him. By placing existing art in the virtual (he also produced a game based on a Marina Abramovîc performance, The Artist is Present [2010], among other works), Barr asks questions about these kinds of works that really couldn’t be asked otherwise.

Reflection, 2015, Ian MacLarty

MacLarty: interacting art and audience

Finally, rarely is the interaction between art and audience more important than in the work of Melbourne game designer, Ian MacLarty. His work Reflection (2015) continually generates a virtual 3D landscape based on the input of the player’s webcam, intertwining the form of the digital space with the player’s physical movements and environment. As well as the startling intimacy of the player’s own image staring down at them from the sky, any physical action the player makes is reflected in the virtual space in real time. Smiling causes murky yellow pillars to rise from seething, fleshy ground. Raising a hand or tilting the head can displace the avatar’s position in this world, as the ground is raised and lowered depending on the images the webcam is exposed to. It’s a fascinating work which integrates play, time, the virtual and the body in ways that few other games or artworks do.

Emerging from decades of politicised game design manifestos, a desire to challenge and expand ideas of both games and art, not to mention hundreds of years of art practice and theory, artgames in 2016 are beginning to step out of the shadow of their big-budget predecessors. Like most mainstream games, artgames are produced by a depressingly straight, Caucasian, male-dominated group of creators, but the diversity of artists and works is expanding every day. With support from artists, critics and audiences, artgames continue to challenge what it means to be both art and game.

RealTime issue #133 June-July 2016