as the fur flies

john bailey on plays that provoke

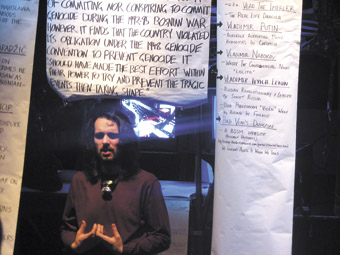

Vlad Mijic, Villanus

photo Rhys Auteri

Vlad Mijic, Villanus

IT’S A CLUNG-TO BELIEF AMONG MANY ADMIRERS OF ART THAT ITS FINEST CREATORS ARE RARELY APPRECIATED DURING THEIR MOMENT ON EARTH. I DON’T KNOW HOW OFTEN THAT CLAIM HAS BEEN EMPLOYED BY THEATREMAKERS TO JUSTIFY AVERAGE WORK, BUT VOCIFEROUSLY NEGATIVE DENUNCIATIONS ARE ALWAYS MORE ENTICING THAN TEPID PRAISE. ANY PIECE ABLE TO INSPIRE ANGER IS, PERHAPS, WORTH A LOOK-IN FOR THAT REASON.

villanus

Welcome Stranger’s Villanus saw a damning critique during the night of my attendance. A vocal audience member made her displeasure known for the last half of the solo show’s duration, sighing and muttering to her companion and asking if they could please leave, now, thank you? When performer Vlad Mijic lay dying, an arrow piercing his gut, apologising for imposing his tale upon his audience, this voice of criticism responded with, “It’s alright darl, it’s just a bit long.” She walked out soon thereafter, the most physical form of criticism available.

Villanus is a profoundly intriguing work, obviously. Mildly engaging performances don’t often occasion walk-outs. Ninety minute monologues that powerfully redefine notions of dramatic structure, character and identity do. Villanus is not without its flaws—there’s a good hour of material stretched out to greater length here. But that good stuff is worth the wait.

Mijic’s Serbian heritage inspires this work. Though he left the country (which wasn’t then a country) at the age of three, his ethnic background later cast him as a villain, one of the bad guys in a war he had nothing to do with. Villanus sees him taking on the role of villain, channelling the monsters of history, offering sympathy to the devil.

It’s a patchwork quilt of vignettes in which Mijic switches identities at an alarming rate—as much to highlight the unstable, projected nature of identity itself as anything else. The set, too, is a junkshop pastiche of roadside hard rubbish, TV screens and cameras, butcher’s paper and packing tape. It’s the stuff Australian culture uses but isn’t willing to offer much value to—just like the dislocated characters Mijic incarnates.

There’s a lot of humour in this ragged work, and much insight, though it lacks the sustained focus necessary to drive home its more provocative points. It’s not for everyone and yes, “it’s a bit long”, but it tends fertile ground worthy of cultivation.

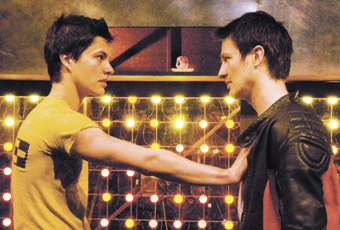

Luke Mullins and Xavier Samuels, Mercury Fur

photo Dan Stainsby

Luke Mullins and Xavier Samuels, Mercury Fur

mercury fur

UK playwright Philip Ridley’s Mercury Fur inspired more public outrage upon its premiere, though Little Death Productions’ recent Melbourne staging saw less controversy and more uniform praise. In Britain, Ridley’s publishers Faber and Faber refused to print the play and several critics denounced the piece as degrading and voyeuristic sadism. It’s anything but.

Mercury Fur’s world is one in which the social contract governing civilisation has been torn up and set afire, giving way to an anarchy both terrifying and entirely plausible. Gangs roam the streets with murderous intent, riots occur with no apparent cause, and governments respond by bombing unruly populations. And amidst the chaos, people get on with getting on. Elliot (Luke Mullins) and Darren (Xavier Samuel) are in the business of organising exclusive parties in which salaried businessfolk indulge their wildest fantasies—murdering a child in a bizarre Vietnam War/Elvis impersonator scenario, for instance. That’s when Elliot isn’t peddling the psychotropic butterflies which descended on London during a sandstorm, or trying to negotiate the excesses of the monstrous “family’‘ which has formed around him: the blind Duchess who is a pit of need and wilful self-delusion; Papa Spinx, a ferocious criminal kingpin who arranges Elliot’s clients; and newcomer Naz, the childlike fool with the butterfly addiction who eventually becomes the crux of the work’s moral dilemma.

It’s thoroughly nasty stuff delivered with enough humour, intelligence and relevance to justify its worst aspects. In the wrong hands, any scene calling for an adolescent shrouded in clingwrap to be hefted offstage awaiting a meathook to the rear would be nothing less than sicko-erotica masquerading as cutting edge theatre, but maybe that’s just me.

One of the work’s strengths is its openness—an audience member’s sense of the piece’s target could easily vary significantly from that of the person they’re sitting next to. Has this dystopia been brought about by a malevolent military-industrial complex? Drug use and hedonism in the young reaching some kind of critical mass? Sheer individualistic greed? Or something else entirely—perhaps something even biblical in scale? All are interpretations supported by the narrative, but it’s that tantalising sense of senselessness creeping around the fringes of the work that gives it such power. We’re trapped in the confines of a ruined building along with these characters, after all, and it’s hard to get the big picture when you’re hiding behind boarded-up windows.

The apocalyptic world of Mercury Fur is bound to alienate some audiences, but it is a text which engages with the alienation of the modern world. Little Death’s version doesn’t revel in its monstrosity but respects the bleak vision it requires. Mullins embraces an atypical role, bringing a convincing rough-hewn edge to Elliot. Aaron Orzech is a discovery as the naïf Naz, and Kelly Ryall’s understated score along with Danny Pettingill’s magnificent lighting bank lend an urgency to the piece that scoffs at the nay-sayers. Here’s hoping for a return season after its Sydney appearance.

holiday

So we get to Holiday. Hard to imagine someone calling for its banning, or rousing themselves enough to walk out. Missing its point would more likely result in a quiet snooze, perhaps. It would be missing out, though, on one of the most fascinating productions in recent memory.

But, to be honest, it would be easy to let Holiday pass you by. Ranters Theatre, under the direction of Adriano Cortese and featuring the impeccable writing of Raimondo Cortese, has long concentrated on the kind of naturalism that seems like anti-theatre, eschewing dramatics in favour of a precise, honest observation. Holiday is both the apogee of this aesthetic and a move in a new direction, introducing theatrical elements previously absented from the more minimalist works Ranters is known for.

It’s almost like one of those 3D magic eye pictures—a seemingly chaotic, random array of dialogue which suddenly, powerfully gains a depth that is almost shocking in its richness. The premise is simple: two men (Paul Lum and Patrick Moffat) lounge beside a large inflatable pool, shooting the breeze in snatches of conversation. Their location is only hinted at—a beachside resort, perhaps, or a suburban backyard. Their relationship is equally vague—they may have just met, or they may be old friends. This is theatre of the moment, in which no word exists before it is uttered, no action before it is performed. The relationship between these two is a process, not a product of the past.

But it’s also misleading to use terms like minimalist or naturalist in relation to Cortese’s dialogue. By reducing extraneous elements, Holiday forces us to listen to the words of these two men, and though their talk initially seems like the listless, even bored ramblings of people on a break from the real world, it’s quickly apparent that profound themes are being confronted—religion, politics, history, love, dreams, art and more are all subtly woven into this tapestry. The very idea of a holiday, after all, is to “get away” from it all, but in doing so these men realise that the alternative is a kind of existential nothingness. Throwing an inflatable ball back and forth in order to do something, anything, thus takes on the kind of true absurdity as effective as anything Beckett could have dreamt up.

The inclusion of brief, baroque songs breaking up the work, along with a sublimely understated set design by Anna Tregloan and an evocative soundscape by David Franzke, anchor the piece in a more sophisticated contemporary milieu than previous Ranters’ productions, and add further aspects to contemplate as this gentle and meditative work unfolds. This is contemporary performance of the highest calibre, wrought with deft skill and tempered with a discerning, unwavering hand. Then again, you might just not get it at all.

Villanus, writer-directors Vlad Mijic, Rhys Auteri, performer Vlad Mijic, Welcome Stranger Productions, Old Council Chambers, Trades Hall, Carlton, Aug 23-Sept 2; Mercury Fur, writer Philip Ridley, director Ben Packer, performers Paul Ashcroft, Gareth Ellis, Fiona Macys, Luke Mullins, Aaron Orzech, Russ Pirie, Xavier Samuel, design Adam Gardnir, sound Kelly Ryall, lighting Danny Pettingill, Little Death Productions,Theatreworks, Melbourne Aug 30-Sept 16; Ranters Theatre, Holiday, writer Raimondo Cortese, director Adriano Cortese, performers Paul Lum, Patrick Moffatt, design Anna Tregloan, sound David Franzke, Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall, Aug 9-22

Mercury Fur plays as part of Griffin Stablemates Program at the Stables Theatre until October 13

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg. 31