australian dance history treasure chest

amanda card: alan brissenden & keith glennon, australia dances, creating australian dance 1945-1965

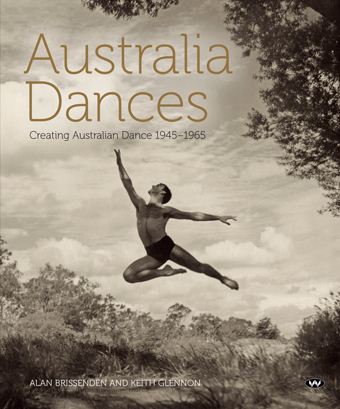

Australia Dances cover, Dancer, William Harvey

photo Walter Stringer, courtesy Wakefield Press

Australia Dances cover, Dancer, William Harvey

ALAN BRISSENDEN AND KEITH GLENNON’S AUSTRALIA DANCES, CREATING AUSTRALIAN DANCE 1945-1965 IS AN OBJECT AS MUCH AS A BOOK, AND A BEAUTIFULLY PRESENTED OBJECT AT THAT.

It does not demand to be read from cover to cover in sequence. If you follow the pages one after the other the dates, people and locations merge in a blur of numbers, names and dance titles. The detail is astounding, for example the authors list (what appear to be) all the possible name changes of companies and organisations throughout the period. But if you choose instead to wander through the amazing array of photographs and replications of wardrobe and set designs, dipping in and out when an association takes your fancy, you will be equally amazed at the writers’ attention to historical detail and avoid the vertigo.

Critical framing of dance in its social, political, economic and cultural context is not the intention of this book. There is a lot of who, what, where and a little bit of how but not a lot of why. Instead, the expressed intention of Australia Dances is to “share in building an awareness of a community of interests, stimulate the interchange of ideas, and provide a record of the exciting period when so much creativity was energising Australian dance.” This it does admirably.

There is, however, a sprinkling of ‘why-not’ as the authors offer up the occasional reflective commentary on the demise of companies and organisations and the lack of innovation in much early local dance (particularly ballet), along with the occasional critique of some of the work. It is interesting (read depressing) to discover the fledgling dance organisations in this period faltered and died one after the other, and rose again, and again, when more funds could be secured. (Reading through this replicated saga I was reminded that the resilience of Australian performing artists also has a history.) The authors also accuse companies like the Borovansky Ballet of not meeting their “obligation to contribute to the vitality of the art it represents.” A revival of old works might satisfy an audience but it “is a truism that no art form can progress and develop without experimentation.”

There are moments when local artists get an ever so gentle, but slightly acerbic ‘serve’. Words like “slight” are used to describe Petite Mozartiana (1939) by Borovansky and Garth Welch’s work for the fledgling Australian Ballet. Rex Reid’s choreography for Melbourne Cup (1960) is called “highly derivative” owing a large “debt” to Les Sylphides and Aurora’s Wedding. Although her creations have a “firmness of purpose and clarity of vision,” a dependence on “the improvisation of individual dancers […] together with her concern for asymmetry, led to a certain untidiness in some of Gertrud Bodenwieser’s ballets.”

The Wheel of Life, 1945,

Bodenwieser Ballet

This book has had an incredibly long gestation period. As Alan Brissenden recalled at its launch in July: “We wrote the book during the late 1950s and early 1960s, when so much was happening in dance in this country.” Keith Glennon was responsible for collecting a lot of the material, travelling from state to state interviewing artists and writing follow-up letters on leads he’d acquired in the field. Asked how Glennon financed his trips, Brissenden recalled that “he hitchhiked a lot of the time. But when he got to Adelaide he didn’t want to face the Nullarbor, so he cabled a great-aunt in England for £50, and she sent it!” Brissenden left for England in 1960: “I had a contract in my pocket and [the book] was to be published in 1961; but a recession rolled in and put a stop to that.” When he returned to Australia he joined the English Department at Adelaide University and, with Glennon, updated the book and tried to get it published again, “but no one was interested.” The letters, photos, clippings and transcript “were stored in a garage” and when Keith Glennon died in 1983 his brothers donated the 22 archival boxes to the Barr Smith Library at Adelaide University and there it all sat until Alan Brissenden retired in 1994 and began to revise the manuscript yet again.

These two men were not only great collectors but also well-connected fellow travellers of the dance community. Glennon was a trained dancer, a theatre technician with JC Williamson and the founding administrator of the Mornington Island Dancers. Brissenden has an Order of Australia for services to the arts and is one of the country’s leading dance critics. They were aficionados. Between them they saw a lot of the work they describe here, and it is those moments when the ‘eye-witness’ nature of some accounts breaks through the stricter historiography that the value of this book is enhanced. We get great moments of description that can only come from being there, like this on Laurel Martyn’s Sentimental Bloke (1952): “To convey changes in time and provide atmosphere, the choreographer left dancers immobile when not immediately concerned in the action of a scene. This provided the ballet with a photo-album quality, clipped the incidents into tidy, page-like sequence, and yet blended them one into another so that there was a continuity of action. This buoyancy was carried through to the ballet’s conclusion; at the end the audience was involved as a wedding photographer, for the curtains opened and closed like a camera shutter on poses contrived by the bridal party.”

There are some oddities as well: the excellent description of the touring and the dancing of the Aboriginal Theatre (1963) is corralled under the title of “Ethnic Dance” and I also thought it odd that the Modern Dance section begins with a return to the Greeks. We move from them to the Romans, the early Christians, dance in the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and are swept on to Isadora Duncan and the early 20th century…all in three paragraphs. I also found the lack of contextual framing in the book a small frustration. Tantalising details of who-made-what-with-whom in a strange ballet like Terra Australis (1946) makes you wonder what it would have been like to be in the room as Tom Rothfield (who wrote the ‘book’), William Constable (décor), Esther Rofe (music) and Borovansky (choreographer) negotiated their way around the ballet’s construction and content. How did these people work together? Why did they make the work? Another interesting, unframed moment is the image of Robert Olup ‘blacked up’ as the “Negro” in Rex Reid’s The Night of the Sorceress (1962). Photographs such as this stimulate interest that is not satisfied in the text.

Generally Australia Dances offers the facts but does not spend much time unpacking or speculating about the meaning of the action in context and time. But, again, that is the intention of the book: to stimulate more research, to give scholars and students a place from which to begin. This publication does not do the work for us: its lack of detailed referencing means the location of much of the material remains ‘secret.’ But this will not bother everyone, and those who are inspired to burrow beneath what Australia Dances has to offer will still need to do the work, scratching at this book’s beautiful, polished, inspirational surface to reveal the stories that lie beneath.

Alan Brissenden and Keith Glennon, Australia Dances, Creating Australian Dance 1945-1965, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2010

RealTime issue #100 Dec-Jan 2010 pg. 26